Jon Levitan is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

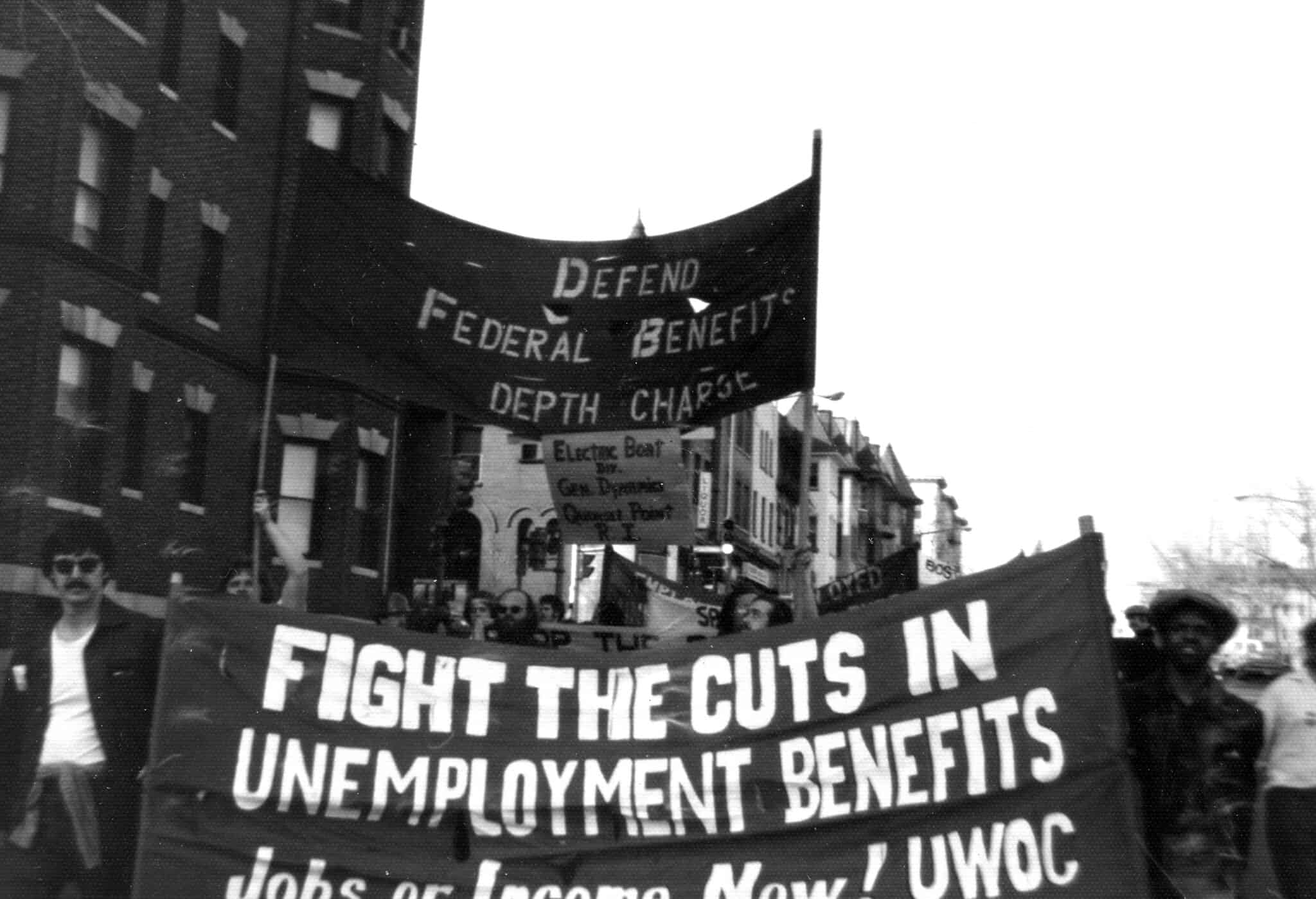

It was not a happy Labor Day for millions of Americans, as they abruptly lost the unemployment benefits that had sustained them for as many as 18 months. Three federal programs that boosted jobless benefits by $600/week (later lowered $300/week) will expire this week. The federal programs were more inclusive than traditional state unemployment insurance because they allowed people to draw benefits for a longer period of time and included many former workers traditionally excluded from unemployment benefits, most significantly gig workers like Uber and Lyft drivers. As a result of the federal programs ending, 7.5 million Americans will lose their benefits—their only source of income—entirely, while another 2.7 million will have their benefits reduced since they will only receive state benefits, which vary in size but are generally paltry compared to the federal benefits put in place during the pandemic.

The Biden administration, for its part, has done essentially nothing to object to or forestall the end of the benefits that kept millions afloat. Instead, the President and his advisors are crossing their fingers and “are now banking on other federal help and an autumn pickup in hiring to keep vulnerable families from foreclosure and food lines.” But that expected autumn hiring spree does not seem like a sure thing, as the Delta variant rages with no end in sight and the labor market numbers show a recovery imperiled by the resurgent virus. While the government hopes for a recovery to eventually mitigate the loss of jobless benefits, the people who have been living on those benefits are feeling that loss right now and are forced to potentially risk their health or face poverty. For example, Lauren Bailey told The Washington Post that she will now lose all unemployment benefits because she was a former Uber driver. Bailey has been applying unsuccessfully for jobs where she can work from home, because she is “afraid of long covid.” Now, as she is left without an income, it is unclear what Bailey and millions of others like her will do.

A new bill being debated in California could reign in one of Amazon’s most abusive labor practices: the practice of imposing outrageously high production quotas on workers, forcing the workers to forgo bathroom and rest breaks. The bill, introduced by Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, would require warehouse employers to disclose the productivity quotas they impose on their workers and ban any quota that prevents workers from taking the breaks they are entitled to under state law, or from using the bathroom when they need to. If passed, the bill would give workers a private right of action to sue their employers for imposing overly strict quotas, and would give state regulators more resources to enforce the health and safety laws imperiled by quotas like Amazon’s. The California Retailers Associations, of which Amazon is a board member, said it would be fine with giving state regulators more data and money to enforce state laws, but outright refused to ever support a bill that includes a private right of action for workers. The bill has passed the state house but faces a more difficult road in the state senate.

Finally, for a Labor Day essay in The American Prospect, Harold Meyerson wrote about the state of the labor movement at this moment in time, which he described as “both hopeful and ominous.” Unions have not been as popular as they are now in over a half a century, and a whopping 77 percent of young people approve of unions. But this popularity has not translated into a new wave of organizing, which Meyerson blames on the fact that American workers do not have the “right to join unions that their government actually enforce[s].” Meyerson laments the fact that the PRO Act seems unlikely to pass but finds hope in NLRB General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo, who he praises for promoting “some directives that put teeth back in the nation’s labor code.” He focuses on Abruzzo’s interest in reviving the Joy Silk doctrine, which would make it much more costly for employers to commit ULPs during an organizing drive. While Meyerson warns that the right-wing courts will likely not approve of a revitalized Joy Silk, he nonetheless commends Abruzzo for pushing the envelope. “Administration officials like Abruzzo have begun to make such changes, but it will require a good deal more power, both on the ground and politically, to ensure that they will continue and endure.”

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

the Supreme Court allows Trump to proceed with mass firings; Secretary of Agriculture suggests Medicaid recipients replace deported migrant farmworkers; DHS ends TPS for Nicaragua and Honduras

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.