Jon Levitan is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

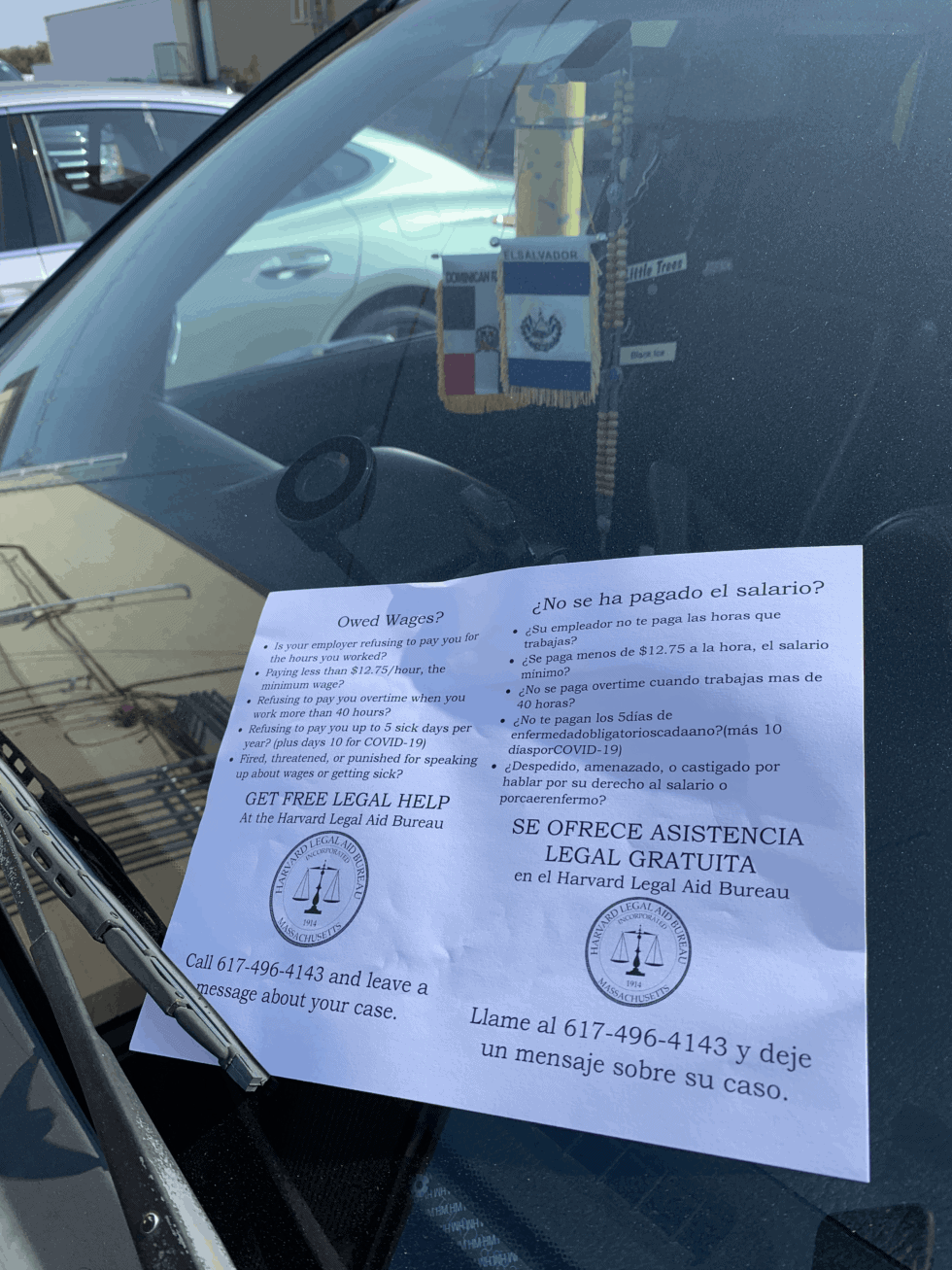

When I learned I would be joining the Harvard Legal Aid Bureau’s (HLAB) Wage-and-Hour practice, I was thrilled. HLAB is a student-staffed legal aid clinic, and the wage practice represents workers who have experienced wage theft or retaliation for asserting their rights to be properly paid. I came to law school to fight for workers’ rights and I could not imagine a better way to spend my final two years of law school than struggling alongside workers and community partners to recover those workers’ lost wages. As I look back now, through nearly three quarters of my time in HLAB, my high expectations were easily met.

I cannot possibly match Juan’s beautiful tribute to the Wage practice from last spring, but suffice it to say that it has been the most rewarding and meaningful part of my law school career. I want to use this post to discuss a consistent challenge we have faced in the Wage practice: actually collecting the judgments we win in wage theft cases. Right now the tools we have for collecting the money our clients have earned are far too inadequate. Some in the labor movement have suggested criminalizing wage theft—and indeed it has been criminalized in Queensland, Australia—but that solution is morally wrong and strategically insufficient. Instead, we should create harsher non-criminal penalties for wage thieves, easier methods to target the biggest industry companies who benefit—directly or indirectly—from wage theft, and systems that pay workers quickly rather than forcing them into slow and often ineffective litigation.

When I joined HLAB at the beginning of my second year of law school, my cynical mind expected Wage and Hour laws to be horribly unjust and make it difficult for workers robbed of their wages to recover them in court. As it turns out, the laws on the books are decent, at least in Massachusetts where we exclusively practice.

Massachusetts’s Wage Act provides for treble damages, allowing workers to receive three times the amount they were originally owed if their employer did not pay them the minimum wage, overtime, or any other amount they were owed under the statute, including even sick time; FLSA—the federal equivalent—only provides for double damages. The Wage Act includes a timely-payment provision, which allows a worker to receive treble damages for wages promised even if the employer paid them the minimum wage or above (FLSA does not include this provision, so a worker could only seek damages for breach of contract—single damages—if they were promised $20 per hour but paid only $15 per hour). Thanks to a Supreme Court decision from 1946 called Anderson, once a worker simply makes a showing that they have performed work for which they have not been paid, an employer who fails to produce full records of hours worked and wages paid is liable for even an estimate of the wage theft. This, in essence, relieves the worker of the potentially onerous burden to show exactly how much in wages was stolen from them. Finally, the fact that Massachusetts uses the ABC test for employee/independent contractor questions means more workers get the benefits of the Wage Act (although Uber and Lyft are trying to recreate Prop 22 in the Bay State and define gig workers as independent contractors).

The upshot of this legal regime is that, in general, when we bring a case on behalf of a worker who has experienced wage theft, we receive a favorable judgment more often than not.

But as I’ve learned, getting that initial judgment too is often only half the battle. We consistently have trouble collecting those judgments from employers. The employers we have trouble collecting judgments from fall into one of two buckets. First, there are the recalcitrant employers, who outright refuse to pay and drag out the process for as long as possible to evade responsibility. Second, there are employers who actually cannot pay. So many of these employers are in the construction industry, an industry where wage theft is rampant and seemingly baked into the system. The direct employers are subcontractors who are often just a single person who may have been stiffed by a general contractor or who bid so low that they would never have been able to pay their workers. This is devastating to our clients, who all live paycheck to paycheck and need to be paid on time and in full to make ends meet.

We do not currently have enough tools to hold these employers accountable. Courts cannot, ultimately, force someone to write a check. We can file a Supplementary Process action and have the employer come back into court to explain why they haven’t paid. That’s a pretty toothless option, even if we tend to try it in most cases. We can garnish wages, profits, or attempt to seize assets. But too often those options are not practically available when suing more informal employers like subcontractors. There is one more avenue which we do not pursue as a practice. We could theoretically seek a Capias, which is like holding someone in contempt; it is a civil arrest warrant for failure to satisfy a judgment. But HLAB, rightfully, has an anti-carceral policy and we steadfastly refuse to bring the criminal system into our civil cases. Even if it were possible to put aside the moral imperative not to expose people to the violence of the carceral system, criminalizing wage theft doesn’t actually help the workers get the money they are owed, as former Wage practice chair Dave McKenna explained on Twitter.

There must be better, non-carceral tools for workers to collect the money that they have earned. New York took a step in the right direction recently, when it passed a law making general contractors liable for wage theft committed by subcontractors in the construction industry. Likewise, here in Massachusetts, Somerville passed an ordinance that strips any business that commits wage theft of its license to operate. These can be powerful tools, and more legislatures should enact them. For the recalcitrant employers especially, a penalty like stripping them of their license to operate is a powerful disincentive. But a problem as large as wage theft, where employers steal billions from their workers each year, requires creative solutions, especially when there are employers who do not have the money in their account to pay their workers. Wage theft is structural and all employers benefit from it by making workers even more precarious and powerless. Because wage theft is so endemic to certain industries, and indeed our economy as a whole, that it does not strike me as unreasonable to create a social insurance fund to ensure workers are paid what they are owed quickly rather than forcing them into slow and inefficient litigation. The fund could be a tax on large employers in certain industries where wage theft is prevalent, and wage thieves would still be subject to harsh civil penalties. Whatever it is, workers desperately need better tools to make sure their checks actually come through.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

the Supreme Court allows Trump to proceed with mass firings; Secretary of Agriculture suggests Medicaid recipients replace deported migrant farmworkers; DHS ends TPS for Nicaragua and Honduras

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.