Alexandra Butler is a student at Harvard Law School.

On Friday, the Bureau of Labor Statistics announced that nonfarm employment slightly increased by 49,000 jobs in January, bringing the national unemployment rate to 6.3%. Yet, there continues to be a disparity in job gains among different sectors. Notably, while professional and business service payrolls increased by 97,000, the leisure and hospitality sector lost 61,000 jobs.

In addition, last week, 779,000 people applied for state unemployment benefits. This marks the third time in a row that the number of new weekly claims has decreased, prompting economists to note that “[w]hile still alarmingly high, . . . [the numbers are] better than the spike that occurred at the beginning of January.” Though states have reopened, the uncertainty of the pandemic has still left some industries unsure whether they will be able to fully maintain their payrolls, as Zachary reported on Monday. For many, “a crucial part of this rebound” will be economic stimulus.

One particular difficulty that the pandemic has exacerbated is long-term unemployment. Defined by the Department of Labor (DOL) as at least a 6 month period without work, this problem plagues at least 4 million people in the United States. As the pandemic has permanently eliminated jobs, many workers have been pushed out of the labor market. As their time outside of the workforce increases, so does the risk that they will never return. For these workers, the consequences can impact all areas of life, leaving those within lower-income brackets especially vulnerable and without a sufficient safety net.

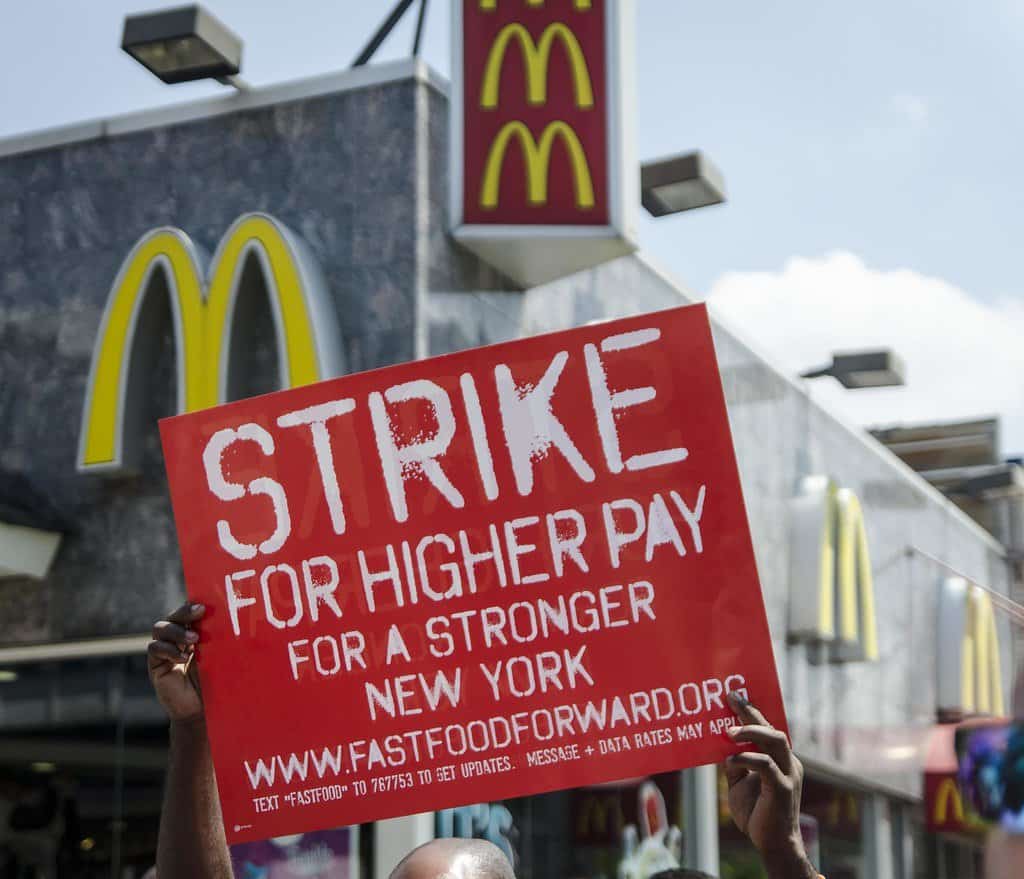

On Thursday, Senate and House Democrats reintroduced the Protecting the Right to Organize Act (PRO Act). By supporting and protecting workers and the unions that represent them, the PRO Act will address problems that workers face – for example and most relevantly, unsafe working conditions during the pandemic. This pro-union legislation facilitates worker organization and protest. As a result, it ensures that workers no longer “lack[] the ability to stand together and negotiate with their employer.” For example, under the Act, the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) would have new enforcement capabilities to prevent employer retaliation against employees who exercise their right to unionize. Though the Act was successful in the House of Representatives last year, many Republicans and pro-business activists believe that the Act is “bad for workers, employers and the economy.”

As employers consider plans to roll-out the COVID-19 vaccine to its workers, some note the role that workers’ compensation can play in assuaging any safety concerns that employees may have. The essential theory is that workers who have negative side effects from the vaccine would qualify for workers’ compensation, state-run programs that provide redress for worker “injury or illness [that] . . . ‘arises out of and in the course of employment.’” If such side effects are covered, employees would be guaranteed a remedy (though they would lose the ability to bring individual lawsuits against their employers, along with the potential to receive a larger amount in monetary damages). Whether vaccine side effects satisfy the “aris[ing] out of test,” however, largely depends on the actions of the employer. For example, many employment experts agree that any sort of vaccine mandate would put worker compensation into play. This could serve as a potential incentive for employers who want the added protection against individual lawsuits. Yet, on the other hand, scholars and lawyers note that instituting a mandate and over-emphasizing worker compensation could undermine employer efforts when it comes to widespread vaccination. Specifically, such actions could have negative consequences for the workforce in general and for worker willingness to take the vaccine.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]

June 27

Labor's role in Zohran Mamdani's victory; DHS funding amendment aims to expand guest worker programs; COSELL submission deadline rapidly approaching

June 26

A district judge issues a preliminary injunction blocking agencies from implementing Trump’s executive order eliminating collective bargaining for federal workers; workers organize for the reinstatement of two doctors who were put on administrative leave after union activity; and Lamont vetoes unemployment benefits for striking workers.

June 25

Some circuits show less deference to NLRB; 3d Cir. affirms return to broader concerted activity definition; changes to federal workforce excluded from One Big Beautiful Bill.

June 24

In today’s news and commentary, the DOL proposes new wage and hour rules, Ford warns of EV battery manufacturing trouble, and California reaches an agreement to delay an in-person work mandate for state employees. The Trump Administration’s Department of Labor has advanced a series of proposals to update federal wage and hour rules. First, the […]