Tascha Shahriari-Parsa is a student at Harvard Law School.

Yesterday afternoon, the NLRB’s new General Counsel Jennifer Abruzzo, sworn-in just a few weeks ago, released a detailed memo alluding to plans to reform labor law through transforming Board precedent. The memo identifies types of cases that would be “mandatory submissions to advice” for reexamination by the Regional Advice Branch and the General Counsel’s office when necessary, and in so doing invites the submission of cases that would help the Board implement changes in Board precedent.

The first section of the memo discusses some of the recent shifts in board law under the Trump-nominated NLRB. Abruzzo follows former acting GC Peter Ohr (and much less importantly, my earlier piece on this blog) to suggest that the Board should overturn the narrow reading of Section 7 in 2019’s Alstate Maintenance. This would expand what qualifies as “concerted” activity, especially whether activities that tend to produce concerted activity—like an individual speaking out to management about her and her coworkers’ concerns—qualify as concerted. It would also expand what counts as “for the purpose of . . . mutual aid or protection”: for example, whether Section 7 protects workers wearing Black Lives Matter masks from retaliation.

The GC memo also discusses shifting the Board’s workplace civility doctrine. Until 2020, otherwise protected concerted activity could generally lose Section 7 protection for being abusive only if it was “opprobrious” or “egregious or flagrant,” which depended on the circumstances of and surrounding the activity. If it occurred on the picket line, an abusive statement had to rise to the level of a “threat of violence” to lose protection. As Fred has explained on this blog, in 2020, General Motors abandoned the Board’s setting-specific analysis and reinstated the 1980 Wright Line test for all abusive conduct. Under Wright Line, a successful Section 7 claim against an employer for retaliating against an employee who uttered abusive words, even on a strike picket line, would require proof that the employer had animus against the Section 7 activity, that the employee’s protected activity was a “motivating factor” in the employer’s decision to take adverse action against them, and that the employer wouldn’t have taken the same action in the absence of the Section 7 activity. The memo suggests that the Board would overturn General Motors and return to site-specific standards for balancing workplace civility with Section 7 rights.

The memo also suggests reviving some much older Board doctrines. One of these is the Joy Silk Bargaining order. An employer violates Section 8(a)(5) of the NLRA by refusing to bargain with a union that has majority status. Generally, this violation does not occur if the employer can establish that it had a good faith doubt about the union’s majority status; however, the Joy Silk Doctrine made it so that if an employer engaged in an unfair labor practice, its defense of a good faith doubt would subsequently disappear. After employers campaigned against it, the Joy Silk bargaining order was abandoned and watered down in the late 1960s. Abruzzo looks to reintroduce it.

The GC memo also expresses a desire to address rules governing employer handbooks (especially the standard used to determine whether handbook rules interfere with the exercise of NLRA rights when they do not facially prohibit protected activities but might be reasonably construed as doing so), confidentiality provisions in separation agreements (for example, the lawfulness of a severance agreement that effectively prevents a retiring employee from assisting in a Board investigation), the employer’s duty to bargain, the right to strike (such as overturning the Board’s prohibition on intermittent strikes), employee classification (including the misclassification of drivers as independent contractors), remedies (including compensatory remedies in cases of a failure to bargain), jurisdiction over religious employers, union dues (including overturning a case finding that an employer may unilaterally cease dues remittance following contract expiration), union access, Weingarten rights, and many other topics. Overall, the memo signals an ambitious metamorphosis of labor law through a string of Board rulings over the next few years.

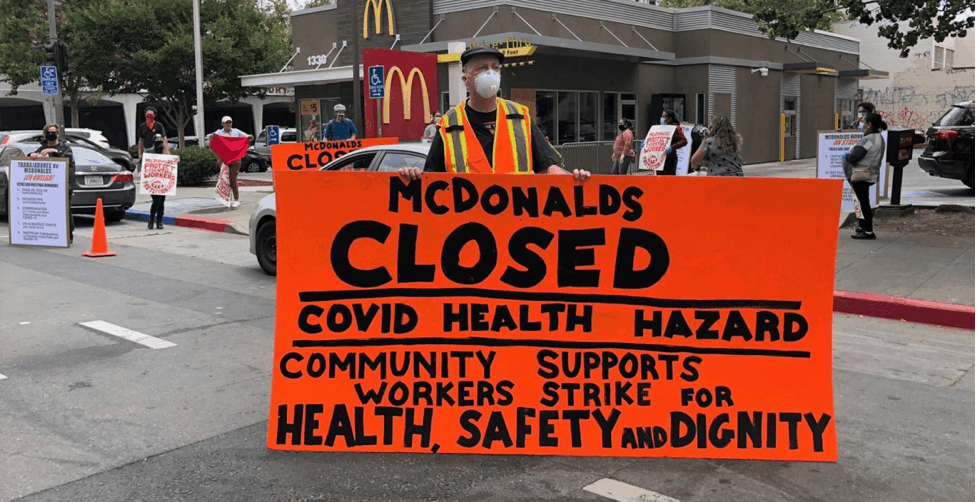

In other news, on Thursday, cooks and cashiers at a McDonald’s in Oakland, California, where twelve workers and eight of their family members had previously tested positive for COVID-19, signed a settlement with McDonald’s in which the restaurant agreed to various COVID-related safety measures. Following a similar settlement two weeks earlier in Chicago, the Oakland settlement comes after a 33-day strike—one of the longest in McDonald’s history—as well as a lawsuit filed by workers and their family members for which a judge granted a preliminary injunction on this day last year. The lawsuit was based on a novel application of public nuisance doctrine to safeguard the health and safety of workers. As Maxwell described in more detail in March, public nuisance is typically defined as when a defendant’s conduct creates “an unreasonable interference with a right common to the general public” and has traditionally been used to address property owners infringing on the rights of the public—such as a smelly cattle field lot near a populous area. The successful application of the doctrine to workplace safety in a pandemic follows a similar settlement with employees of a McDonald’s restaurant in Chicago, reached just two weeks earlier. In the Chicago case, a judge had also granted a preliminary injunction last spring, which the settlement rendered permanent.

“We’re not going to get tired of fighting,” said Angely Rodriguez, a McDonald’s striking worker, last spring. “And we’re going to keep fighting. And we’re gonna fight with more force, because we demand dignity so that no other fast food worker passes through what I went through.”

On Thursday, the Supreme Court halted a portion of New York State’s eviction moratorium, which could quickly lead to thousands of evictions. The blocked provision previously prevented the eviction of tenants who filed forms stating that they suffered economic hardship as a consequence of the pandemic, though tenants who provide evidence in court would not be affected by the ruling and would still be covered by the moratorium. The case rested on the landlord’s argument that their due process rights were violated by allowing eviction proceedings to be halted without the involvement of courts, depriving landlords of their access to the legal process.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 23

Supreme Court hears cases about 10(j) injunctions and forced arbitration; workers increasingly strike before earning first union contract

April 22

DOL and EEOC beat the buzzer; Striking journalists get big NLRB news

April 21

Historic unionization at Volkswagen's Chattanooga plant; DOL cracks down on child labor; NY passes tax credit for journalists' salaries.

April 19

Alabama and Louisiana advance anti-worker legislation; Mercedes workers in Alabama set election date; VW Chattanooga election concludes today.

April 18

Disneyland performers file petition for unionization and union elections begin at Volkswagen plant in Tennessee.

April 18

In today’s Tech@Work, a regulation-of-algorithms-in-hiring blitz: Mass. AG issues advisory clarifying how state laws apply to AI decisionmaking tools; and British union TUC launches campaign for new law to regulate the use of AI at work.