Isabelle Holt is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

Incarcerated workers harvest corn, peppers, and melons in Colorado, fight wildfires in California, clean the governor’s mansion in Nebraska, and manufacture everything from mattresses to body armor. Just like other employers, the Bureau of Prisons sets inmate-worker job descriptions, pay grades, and performance standards for federal prisons, and state prison systems do the same. Like other employees, prisoners are required by their employer to clock in and work a minimum number of hours a day. Yet, despite working for years while in prison, incarcerated workers remain ineligible for unemployment insurance upon their release.

That’s because, in the eyes of the UI system, the work performed by incarcerated workers does not count toward the accrual of UI benefits. The Thirteenth Amendment, while abolishing slavery in the United States, created a loophole allowing forced labor as the punishment for a crime. This excluded incarcerated work from the definition of employment as well as the labor protections created by the Fair Labor Standards Act and UI benefits.

This post will examine the structure and history of the UI system, why the base period earnings requirement should be removed or adjusted for incarcerated workers, and how UI for formerly incarcerated workers is a normatively good policy choice. In short, it will argue that formerly incarcerated workers should be eligible for UI if they cannot find work upon their release from prison.

The Structure of the UI System

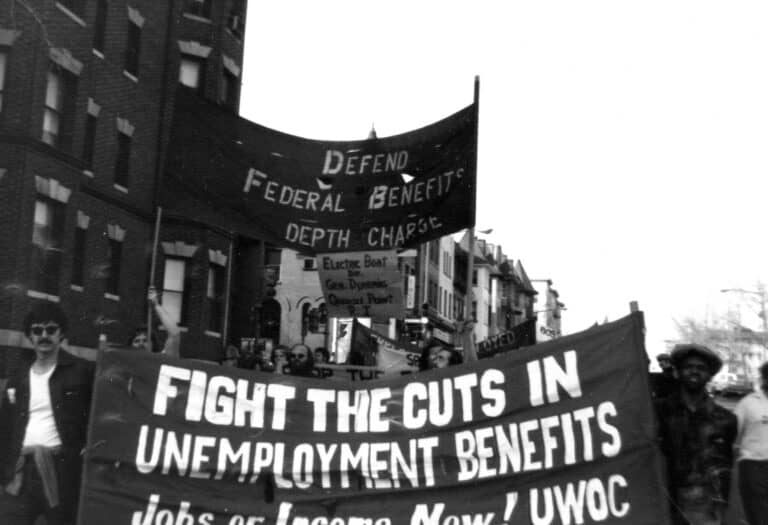

The current unemployment system was created in 1935 as part of the Social Security Act, and recognizes only a slice of all work performed. UI was designed to systemically disadvantage low-wage workers, informal workers, and workers of color — and to completely exclude incarcerated workers. Beyond this history of slavery and discrimination, there is no reason that incarcerated workers should not be eligible for UI benefits.

UI eligibility requirements are designed to measure a worker’s attachment to the labor force — the rationale being that those who have put sufficient labor into the system are those who “deserve” UI. The unemployment system is funded primarily by state taxes on employers and secondarily by the Federal Unemployment Tax Act, which pays the administrative costs of the program. While exact requirements vary by state, to qualify for UI, workers generally must: 1) be able and available to work, and actively seeking work; 2) have lost their job through no fault of their own; and 3) have earned a certain amount during the “base period” before becoming unemployed.

Formerly incarcerated workers should clearly satisfy the first two eligibility prongs. They are able and available to work and lost their prison employment because they were released (i.e., through no fault of their own). All that stands in the way of their UI eligibility is including earnings while incarcerated in “base period” earnings calculations. Given that states have extensive flexibility in determining UI eligibility, such a modification is within the power of state governments. If states waived or modified base period earnings requirements and incarcerated workers’ employers paid into the UI system — UI for incarcerated workers could function similarly to traditional UI.

Despite their low earnings, incarcerated workers are just as “attached” to the labor market as UI-eligible workers. Many incarcerated workers work full-time while in prison and their labor affects the economy outside prisons. UNICOR, the Federal Prison Industries program, makes half a billion dollars in net sales and millions of dollars in profits annually while paying inmates between $0.23 and $1.15 an hour. State prisons generate more than one billion dollars from prison labor and over 4,100 private corporations profit from the labor of incarcerated workers in the United States. Because incarcerated workers are not considered employees, they are paid far below market value, making them unable to meet base period earnings requirements.

Incarcerated workers could be eligible for UI if states waived or adjusted base period earnings requirements or if incarcerated workers were compensated at market rate for their labor. Just like any other employer, those who employ incarcerated workers can and must pay into the UI system for their employees.

The Case for UI for Incarcerated Workers

Not only is UI for newly released incarcerated workers feasible, it is vital. Workers are unable to meaningfully save while incarcerated and face high barriers to re-entering the workforce. Most of what workers earn while incarcerated goes back into the prison system through high prices for telephone calls or basic sanitary supplies and prisons charging working inmates for the cost of incarceration. For example, as profiled by NPR, when Dominique Morgan was released from prison after working twelve hours a day for a decade making tablecloths for Oriental Trading, she had only $300 in savings and when she applied for the same job she had while incarcerated, Oriental Trading told her they did not hire felons. Formerly incarcerated people are unemployed at a rate higher than the highest unemployment rate during the Great Depression, and are unemployed for longer periods than workers who have not been incarcerated.

Even beyond the moral and logical imperative to recognize incarcerated workers as employees, creating a UI system for newly released incarcerated workers is in the state and taxpayers’ best interest. Incarceration costs on average $30,000 per person per year, whereas the average cost of paying a UI claim is between $4,200 and $12,000 a year (most of which is paid by the employer through state payroll taxes). While the low cost of most UI claims indicates the need to overhaul the UI system, even if UI benefits were increased, it would still be in the state’s best interest to provide UI for incarcerated workers.

The strongest predictor of recidivism is poverty. A single incident of recidivism can directly cost taxpayers upwards of $50,000 per person per incident per year, not including public safety or court costs. Unemployment benefits lift people out of poverty. Analysis of the effect of UI on those unemployed after the Great Recession of 2008 found that receiving UI reduced poverty rates of workers by half. Only 56% of unemployed workers were receiving UI at the time, meaning that expanding UI eligibility and access would have pulled many more people out of poverty. Expanding UI eligibility through waiving or adjusting the base period earnings requirement to include the wages of formerly incarcerated workers would reduce poverty and therefore recidivism, thus reducing taxpayer costs while shifting the cost of such a UI system onto those benefiting from prison labor.

Conclusion

Incarcerated workers should be compensated fairly for their labor while incarcerated and be eligible for UI benefits upon release. Even access to only market-rate UI benefits would substantially reduce poverty on re-entry, allow incarcerated individuals to re-enter society with dignity, and provide support to workers during the critical time immediately after release.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 15

The Department of Labor announces new guidance around Occupational Safety and Health Administration penalty and debt collection procedures; a Cornell University graduate student challenges graduate student employee-status under the National Labor Relations Act; the Supreme Court clears the way for the Trump administration to move forward with a significant staff reduction at the Department of Education.

July 14

More circuits weigh in on two-step certification; Uber challengers Seattle deactivation ordinance.

July 13

APWU and USPS ratify a new contract, ICE barred from racial profiling in Los Angeles, and the fight continues over the dismantling of NIOSH

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

the Supreme Court allows Trump to proceed with mass firings; Secretary of Agriculture suggests Medicaid recipients replace deported migrant farmworkers; DHS ends TPS for Nicaragua and Honduras