Isabelle Holt is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

Traditionally, psychologists need to be licensed in the state where their clients are located and are not allowed to practice in states where they are not licensed. As many patients relocated beyond the reach of their psychologists’ licenses during the pandemic and mental health needs soared, states enacted licensure exceptions that allowed psychologists to see patients remotely out of state. As these exceptions are lifted, and especially given the wide acceptance of telehealth, patients and psychologists alike are questioning the need for licensure that limits practice areas to a single state.

Imagine if each time you traveled out of state you had to pass the driver’s license test of every state you drove through. You don’t need to do this thanks to an interstate compact that allows you to maintain a single driver’s license but drive in any state. Similarly, the Psychology Interjurisdictional Compact (PSYPACT) is an interstate compact designed to facilitate the practice of telepsychology and temporary in-person psychology across state boundaries. PSYPACT thus allows for continuity of care and simplifies burdensome licensure requirements. While there is a constellation of interests at stake in PSYPACT, including public and individual health, this post will first explain what PSYPACT is, then examine PSYPACT’s benefits to practitioners, and finally turn to interjurisdictional compacts as a worker issue.

What Is PSYPACT?

PSYPACT was conceived of by the Association of State and Provincial Psychology Boards (ASPPB), which is the alliance of state, provincial, and territorial agencies responsible for the licensure and certification of psychologists throughout the United States and Canada. ASPPB created mobility programs such as PSYPACT to “promote responsible professional mobility for psychologists in all ASPPB jurisdictions.”

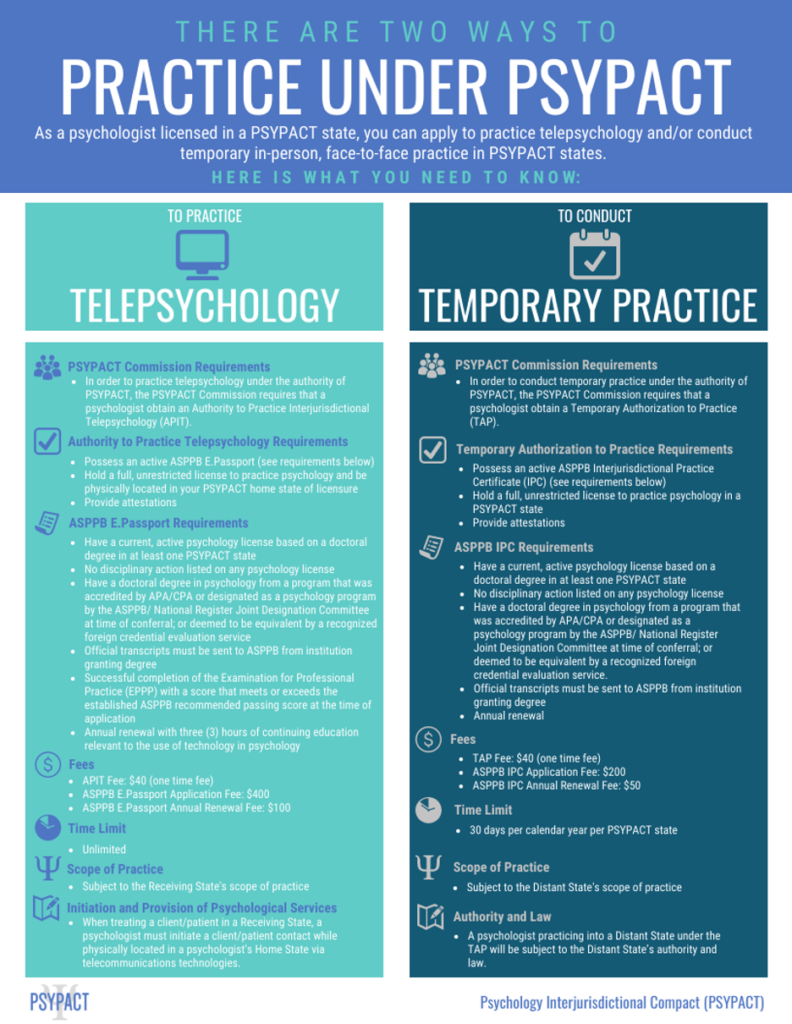

PSYPACT allows licensed psychologists that meet certain requirements to do two new things: (1) practice telepsychology in any state that is a member of the compact and (2) conduct a temporary in-person practice in any PSYPACT state for 30 days each year. PSYPACT specifically covers psychologists and does not cover Licensed Clinical Social Workers or any other kind of therapist or counselor.

Why Have PSYPACT?

Transferring licensure is time consuming and expensive for psychologists and maintaining licensure in multiple states is doubly time consuming and expensive.

Let’s take for example a practitioner living in Philadelphia, licensed to practice in the state of Pennsylvania. Such a practitioner’s clients may move frequently between Pennsylvania, New York, New Jersey, and Delaware given these states’ proximity. Without PSYPACT a practitioner who maintained a license in each state would pay around $1300 every two years to maintain her licenses. In addition to the expense, each state has different renewal dates and number and types of continuing education hours required so hours earned for one state don’t necessarily count for another. Whereas, with PSYPACT, she could pay only $100 a year for licensure and benefit from a streamlined renewal process.

While legislators have framed PSYPACT as increasing consumer access to a broad range of psychological services, streamlining licensure requirements so psychologists can maintain their practices, reach the populations they are interested in serving, and understand what law applies to recordkeeping, mandatory reporting, and confidentiality, is a worker issue.

Interjurisdictional Compacts as a Worker Issue

26 states are currently participating in PSYPACT and adoption of PSYPACT is snowballing; 11 of these jurisdictions passed PSYPACT legislation in 2021. An additional 8 jurisdictions have pending legislation. PSYPACT has gained so much momentum that states yet to enter the compact are concerned that failure to participate will be a disincentive to psychologists to practice in their state.

While there seems to be consensus that PSYPACT would increase patient access to care, especially in rural areas, it remains an open question if interstate licensure will equally benefit psychologists as workers in different states.

While virtually nothing has been written about the potential drawbacks of interstate licensure for psychologists, other caring professions, such as nurses, which have had interstate licensure for longer present a more nuanced view. While nurses surveyed in Minnesota overwhelmingly voted to join the interstate licensure compact, nursing unions in Massachusetts, Washington, and Oregon opposed interstate licensure. These unions argue introduction of interstate licensure will allow nurses from less unionized states with lower wages and lower licensure requirements to provide care remotely, undercutting wages and collective bargaining power. Additionally, because, as is true under PSYPACT, discipline against a practitioner’s license is left to that person’s home state, nurses involved in the same kinds of incidents while practicing in the same state could face different disciplinary action. Finally, certain nursing unions point to the fact that interstate licensure enables care facilities to offload patient care to call centers staffed by nurses in states with lower prevailing wages.

Unlike nurses, however, psychologists are not traditionally unionized. Most psychologists practice in settings that exempt them from union eligibility under the NLRA, such as private practice (29%), where they are largely considered independent contractors. Those who work in certain government settings (10%), private higher education and those employed in private outpatient mental health care and private hospitals (24% combined), are eligible for unionization but only a miniscule 2% were affiliated with a labor union.

By effectively nationalizing the market for mental health care, PSYPACT has the potential to give psychologists access to markets that were previously inaccessible. While it is difficult to generalize, it seems obvious that the interests of psychologists as workers are not uniform. With the increasing nationalization of care one would expect to see psychologists from states where average earnings are low and most clients are unable to afford self-pay fees try to access markets in areas with higher psychologist compensation such as Miami and New York where psychologists bill upward of $200 a session without insurance.

At the same time, there is a huge unmet need for mental health care. One in five people in the United States has a mental illness, however, 57.2% of adults with a mental illness received no treatment. The distribution of psychologists per capita is also highly skewed. While 19% of metropolitan counties lacked a sufficient number of psychologists to meet per capita client needs, 47% of non-urban counties did not have enough psychologists to meet their populations’ needs.

While PSYPACT opens the door for psychologist mobility to underserved areas, it does not create a financial incentive for psychologists to practice there. For efforts like PSYPACT to have truly redistributive effects, as psychologists have long recognized, psychologists need greater collective bargaining power with both private and public insurers. Coupled with the flexibility of PSYPACT, increasing insurance reimbursement rates would benefit psychologists as workers. Instead of creating an incentive for psychologists in areas where people cannot afford to self-fund and insurance does not provide a sufficient hourly to try and compete across state lines in preexisting booming mental health markets, increased insurance reimbursement rates would provide psychologists the support they need to use PSYPACT to move into undersaturated and underserved areas.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]

June 27

Labor's role in Zohran Mamdani's victory; DHS funding amendment aims to expand guest worker programs; COSELL submission deadline rapidly approaching

June 26

A district judge issues a preliminary injunction blocking agencies from implementing Trump’s executive order eliminating collective bargaining for federal workers; workers organize for the reinstatement of two doctors who were put on administrative leave after union activity; and Lamont vetoes unemployment benefits for striking workers.

June 25

Some circuits show less deference to NLRB; 3d Cir. affirms return to broader concerted activity definition; changes to federal workforce excluded from One Big Beautiful Bill.

June 24

In today’s news and commentary, the DOL proposes new wage and hour rules, Ford warns of EV battery manufacturing trouble, and California reaches an agreement to delay an in-person work mandate for state employees. The Trump Administration’s Department of Labor has advanced a series of proposals to update federal wage and hour rules. First, the […]