Marina Multhaup is a Senior Associate at Barnard, Iglitzin & Lavitt—a law firm in Seattle, Washington, that represents unions, and a former student member of the Labor and Employment Lab at Harvard Law.

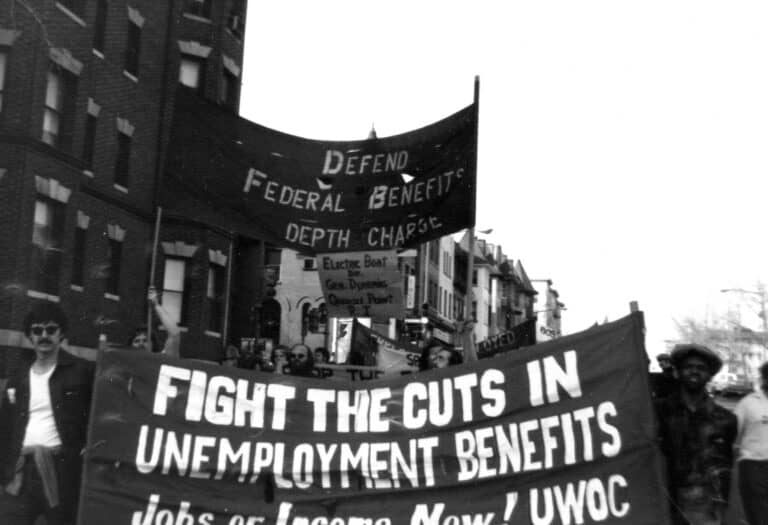

Across the country hundreds of thousands of people are receiving notices from their state unemployment office telling them that they were “overpaid” unemployment benefits and are now in debt to the state. Because most people received expanded federal unemployment benefits, this debt can be in the tens of thousands of dollars. When people cannot repay the debt the state either seizes remaining benefits if the person is still receiving assistance or garnishes wages if the person has managed to find work. Forcing impossible-to-pay debts onto people who are already facing hardship, mostly due to mistakes made by states in calculating unemployment benefits and eligibility, makes no sense. Not only is it impossible for most people to pay this money back, but clawing back benefits from people who did not commit fraud in the middle of a recession is a waste of government resources and detrimental to our collective recovery.

During the first six weeks of the pandemic over 30 million people, or almost 20% of the U.S. labor force, filed for unemployment relief. Almost a year later millions of people are still relying on unemployment insurance to live while the pandemic rages on and jobs continue to be dangerous, scarce, and unreliable. For the past month at least a million people a week filed new claims for unemployment. The leisure and hospitality industry had the highest unemployment rate as of December 2020: that’s cooks, bartenders, cleaners, and front desk workers. Most of those workers are working class and poor people of color and women. Ironically but not surprisingly, the least-hit-hard sector was the financial sector, as the rest of the country collapsed into financial hardship.

There are several reasons why states are declaring that someone has been “overpaid.” Some people applied for unemployment because they believed they were qualified for it but are now, months to a year later, deemed ineligible due to the technical requirements of unemployment insurance qualification. Other people made good-faith mistakes filling out the complicated forms, like getting a date wrong or checking the wrong box. In many cases, it was clerical errors by states themselves that led to these “overpayments.” For example in Pennsylvania it was a computer error that resulted in 30,000 people being “overpaid.” There are examples of criminal-level fraud resulting in overpayment, such as someone taking out multiple claims. However, out of the hundreds of thousands of people who are being forced to pay back benefits, fraudulent claims represent only a small fraction of people affected.

People who receive unemployment assistance do not have tens of thousands of dollars to pay to the state. Even in “normal” times this practice is cruel and makes no sense, and in a pandemic demanding unemployment benefits back from those who needed the lifeline makes even less sense. People who file for unemployment insurance are facing hardship, they need money to pay their bills and make it through to their next paycheck. Unemployment insurance doesn’t go into savings or add to a preexisting financial cushion, it goes right back out the door in food, clothing, rent, utilities, and—god forbid—perhaps a few extra items like new toys for children or a family trip to the zoo. A woman laid off in March from her job at a hotel was told she had to repay $12,500 in unemployment benefits, but she had already used the money to support her family. “It’s all gone,” she said, “I can’t afford to pay it back.” In a pandemic, the point of unemployment benefits isn’t just to alleviate poverty but also to stabilize the entire economy, which has been teetering on the edge of a cliff since the pandemic started. Sending people into impossible debt, when there aren’t jobs available or any relief in sight, has a “cascading effect,” causing not only further poverty of those directly affected but also has wider economic effects like closures of small businesses and negative public health consequences.

Sticking people with the burden of navigating the unemployment insurance process perfectly is not only morally and economically wrong, but also hypocritical. The unemployment insurance system is known to be one of the most archaic and complicated systems in our government. Since the start of the pandemic the Department of Labor has issued over thirty six different “Guidance” documents, which states have struggled to implement. State unemployment offices are under-resourced, under-staffed, and were totally unprepared to deal with this crisis. People have reported example after example of “Kafkaesque” encounters with state unemployment agencies all around the country: claims going missing, waiting on the phone for hours to speak to someone, websites crashing, weeks of delays, and no one to talk to about it, no authority to ask for help.

Congress passed a waiver option in its December coronavirus stimulus bill aimed at alleviating this nonsensical policy. According to the bill’s text, state unemployment agencies can waive repayments if it determines that “the payment of such pandemic unemployment assistance was without fault on the part of any such individual; and such repayment would be contrary to equity and good conscience.” While the waiver provided some opportunity for relief where before there wasn’t any, it’s not enough. The waiver language is restrictive—what does “without fault” mean? Someone who filled out a form incorrectly, someone who spent day after day on the phone trying to ask the agency which form to file and finally just made their best guess, would they be at “fault”? Because the waiver option was only passed in December, we don’t yet know how states and potentially courts will interpret this. But in a pandemic raging over the worst recession in U.S. history, asking anyone to give up their precious benefits or income to pay back a state debt should de facto violate society’s “equity and good conscience.”

Congress has the power to stop this. Congress should legislate that no state can extract previously paid benefits from people unless there was criminal-level fraud involved. Congress should modify the waiver language in the next stimulus bill, changing the “without fault” language to “absent intentional fraud,” or something to that effect. Congress should include direct payments to state unemployment agencies to cover the debts that states are facing. This would direct precious state resources away from trying to claw back money from poor people of color and towards trying to help people get the relief they need. Finally, Congress should not allow states to garnish unemployment benefits or future wages to cover overpayments. Withholding precious benefits or wages for hundreds of thousands of low-income workers, due mainly to the inefficiency of state bureaucracies, will only entrench racial-economic disparities and worsen our national crisis.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 1

In today’s news and commentary, the Department of Labor proposes to roll back minimum wage and overtime protections for home care workers, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit by public defenders over a union’s Gaza statements, and Philadelphia’s largest municipal union is on strike for first time in nearly 40 years. On Monday, the U.S. […]

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]

June 27

Labor's role in Zohran Mamdani's victory; DHS funding amendment aims to expand guest worker programs; COSELL submission deadline rapidly approaching

June 26

A district judge issues a preliminary injunction blocking agencies from implementing Trump’s executive order eliminating collective bargaining for federal workers; workers organize for the reinstatement of two doctors who were put on administrative leave after union activity; and Lamont vetoes unemployment benefits for striking workers.

June 25

Some circuits show less deference to NLRB; 3d Cir. affirms return to broader concerted activity definition; changes to federal workforce excluded from One Big Beautiful Bill.