Yoorie Chang is the Project Manager for the Clean Slate for Worker Power Project at Harvard Law School’s Center for Labor and a Just Economy.

Thea Burke is the Communications Associate at Harvard Law School’s Center for Labor and a Just Economy

Earlier this month, CLJE announced that Michelle Miller, formerly of Coworker.org, has joined the team as the new Director of Innovation. Michelle is leading the Center’s research, strategy, and programming on the impact of artificial intelligence and emerging technologies on the experience of work, and how workers can meet the challenges and opportunities posed by technology.

In this interview, Michelle shares perspectives on the potential threats AI poses to autonomy, privacy, and decision-making in the workplace, and what new approaches to protecting workers’ rights could look like in a world where technology in need of regulation is rapidly developing. Michelle also shares why we shouldn’t be afraid of technology, but rather how we can address the inevitable changes and ethical challenges it brings to workers.

What is the relationship between the tech sector and most workers? What are the ways new tech can impact labor activity like organizing and collective bargaining?

Most workers encounter some kind of automated system in the course of performing their jobs. This can take many forms: pay and benefits software, automated hiring systems, apps that “help” workers track wellness to lower insurance costs, algorithms for task allocation and management…the list goes on. While these tools can, in some cases, be helpful, many rely on an invasive system of data extraction and surveillance to track, manage, punish, and reward workers based on an opaque set of automated standards. Activists and researchers have raised concerns for more than a decade about the impact of algorithmic decision-making and increased digital surveillance on peoples’ ability to exercise basic rights at work. In short, when your boss is a computer, it’s another barrier to effectively being able to advocate for your rights. And when that computer is built on data that contains pre-existing biases according to race, gender, ability, immigration status, etc., it raises significant concerns for the proliferation of this software across the workforce.

What is something we might not know about the way data is used at work?

The first thing to know is that data collection requires constant surveillance by the software that uses it. Many people have explained this process in detail, but, for example, if you’re an office worker and HR is using performance management software, something is not only tracking every email you write or call you do, it’s likely drawing conclusions about your affect and behavior. And if it’s off-the-shelf software, there’s a chance it’s selling that data to brokers who then package and sell that data to others. There’s a huge market of shadowy, third-party brokers profiting off of the data that is collected from us and, in the course of our jobs, our choice to opt in or out of that market is constrained by the conditions of our employment.

Artificial intelligence seems to be the primary focus of most tech sector coverage and regulatory efforts right now. Can you explain how AI might show up at work? Does it function like the other workplace software you described?

It’s important to think about AI and its regulation as part of a continuum of workplace software development. Artificial intelligence relies on massive data sets (including copyrighted material), significant computing power, and networks of humans doing microtasks to perform some basic cognitive tasks that have traditionally been performed by paid employees.

So, when we saw the Writers Guild go on strike last summer, one of their concerns was that studios would attempt to use AI for initial script production then use writers to clean it up, thus getting around agreements about pay and crediting. What they negotiated was transparency and consent around the use of AI, limiting the ways in which it could show up. AI can still be used as a tool at the writer’s discretion, but not as a workaround for paying writers. What I think is important about this case is that the use of AI for creative production has an impact on all of us. It’s not just about the writers’ jobs (which are extremely important!). It’s about ensuring that the few mega-tech companies who can afford to build AI models aren’t monopolizing culture production and the stories we tell about ourselves through mass media.

In your opinion, what is one of the biggest threats to workers’ rights when it comes to AI in the workplace?

There is great potential for AI to enhance our work lives when it is provided as a tool – for example, to augment our capacity or take over dangerous tasks. But any time AI is being used to make decisions about peoples’ lives, we’ve got a problem. The technology is too new, too unregulated, too reliant on data that has proven built-in biases to make decisions for and about peoples’ lives – that is, to control workers instead of being controlled by them. And at the human level, this is about basic dignity. We deserve the dignity of negotiating with a human being on things that really matter, not being directed by a system with murky accountability. The direction I see it going is that we won’t entirely replace humans with AI, but that your ability to interact with a human will be directly related to your social and class position. We all deserve better than that.

What are some possible solutions?

As we lay out in the report, solutions require some kind of co-governance model with workers and their chosen representatives. That means giving workers a seat at the table where decisions are made about how AI is used, where it is used and what happens to the data it collects. Scholars like Margaret Mitchell have done impressive work laying out potential structures for intervention. There’s a lot we can do when we find ways for workers to be involved from the outset.

CLJE’s latest report explores mechanisms for worker governance in the deployment of AI and technology in workplaces. The report also emphasizes that it was not born out of a “fear” of technology or its advancements. Can we strike a balance where technology is used to support the autonomous worker?

The worst thing we can do is be afraid of this new technology or to treat it like it’s new at all. It is an evolution of processes that have been in place for years. We are in our best position when we size up what is happening now to the most vulnerable workers and address those issues. The best way to ensure we’re doing this is to – you guessed it – listen to workers. What are people who are working in these jobs saying about their own experiences with and relationship to AI? What do they want from the latest tech developments, not just in their jobs, but in their lives? There are a lot of areas that tech threatens to destabilize that are, frankly, not exactly in great shape to begin with. We should be focused on building a society in which stability and abundance are the baseline for everyone.

Read more about our recommendations for empowering workers in the deployment of AI in the workplace in our latest report, “Worker Power and Voice in the AI Response.”

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

December 13

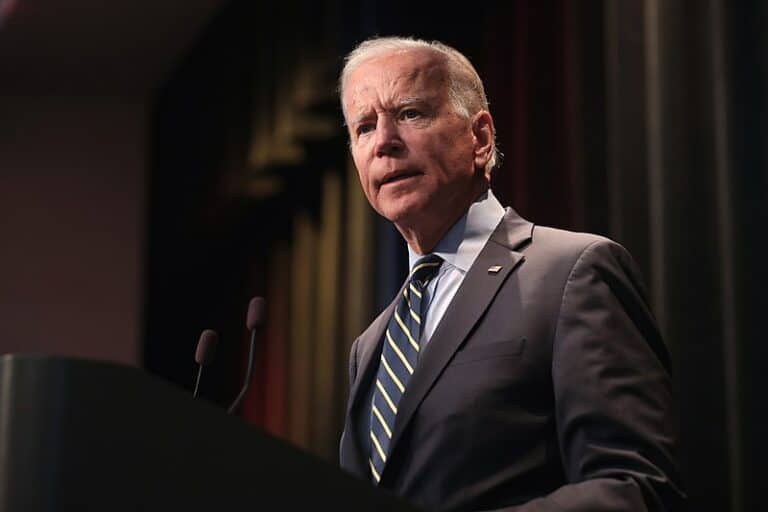

In today’s News & Commentary, the Senate cleared the way for the GOP to take control of the NLRB next year, and the NLRB classifies “Love is Blind” TV contestants as employees. The Senate halted President Biden’s renomination of National Labor Relations Board Chair Lauren McFerran on Wednesday. McFerran’s nomination failed 49-50, with independents Joe […]

December 11

In today’s News and Commentary, Biden’s NLRB pick heads to Senate vote, DOL settles a farmworker lawsuit, and a federal judge blocks Albertsons-Kroger merger. Democrats have moved to expedite re-confirmation proceedings for NLRB Chair Lauren McFerran, which would grant her another five years on the Board. If the Democrats succeed in finding 50 Senate votes […]

December 10

In today’s News and Commentary, advocacy groups lay out demands for Lori Chavez-DeRemer at DOL, a German union leader calls for ending the country’s debt brake, Teamsters give Amazon a deadline to agree to bargaining dates, and graduates of coding bootcamps face a labor market reshaped by the rise of AI. Worker advocacy groups have […]

December 9

Teamsters file charges against Costco; a sanitation contractor is fined child labor law violations, and workers give VW an ultimatum ahead of the latest negotiation attempts

December 8

Massachusetts rideshare drivers prepare to unionize; Starbucks and Nestlé supply chains use child labor, report says.

December 6

In today’s news and commentary, DOL attempts to abolish subminimum wage for workers with disabilities, AFGE reaches remote work agreement with SSA, and George Washington University resident doctors vote to strike. This week, the Department of Labor proposed a rule to abolish the Fair Labor Standards Act’s Section 14(c) program, which allows employers to pay […]