Tascha Shahriari-Parsa is a government lawyer enforcing workers’ rights laws. He clerked on the Supreme Court of California after graduating from Harvard Law School in 2024. His writing on this blog reflects his personal views only.

In today’s news and commentary, an anti-union Apple memo leak; union election filings at a Target store in Virginia; a piece by Steven Greenhouse calling on national labor unions to poor resources into supporting self-organized union efforts; and the UC Berkeley Labor Center’s Low-Wage Work in California Data Explorer.

An anti-union memo from Apple was leaked yesterday. The memo, obtained and verified by VICE’s Motherboard magazine, was sent to Apple store leaders, and contains talking points to combat unionization at apple retail stores. The talking points suggest to workers that that forming a union could lead to a loss of flexibility in granting time off, job promotions based on merit, and “career experiences.”

“There are a lot of things to consider,” one of the memo headings reads. “One is how a union could fundamentally change the way we work.” Under that heading, the memo emphasizes that a union “would actually speak for you on most issues related to work,” going on to remind workers that they may disagree with the union’s approach to something. The memo does not also remind workers that, even if a majority of workers or elected union leadership make decisions that are different from what some or many individual workers desire (as necessarily happens in a democracy), having a union gives workers more of a voice rather than less to countervail the currently unilateral power of Apple to determine wages, working conditions, and all rules governing work for employees. The memo similarly also notes that a future union contract could lead to more rigid rules that impede flexibility of employee assignments, without mentioning that workers have no reason to ratify a contract that makes their situation worse—and “an outside union” can’t ratify a contract for them.

The memo comes after workers at three apple stores filed for union election with the NLRB. One of these is the Cumberland Mall store in Atlanta, which is scheduled to vote starting on June 2 and would be the first apple store to unionize if successful. “We want to have a voice in our workplace,” said Elli Daniel, a store employee and organizer. Their demands include fair compensation, career development, equity, health and well-being, and safety. Apple’s Grand Central Terminal retail store in Manhattan has also filed for a vote, where the organizers—calling themselves “Fruit Stand Workers United”—affiliated with the SEIU-affiliate Workers United on February 21st. The third drive is taking place at the Towson Mall store in Maryland.

Joining the wave of retail organizing, workers at a Target store in Virginia also filed for union election with the NLRB on Tuesday. Workers at the store in Christiansburg, Virginia say they are overstretched and are not seeing their pay keep up with inflation, according to Adam Ryan, who founded Target Workers United three years ago and has been working at the store for five years. Like workers at Apple, Target workers were also subjected to anti-union propaganda from the company which was leaked earlier this year. Target’s training specifically stated that unions could lead to “reduced flexibility and narrowed job descriptions,” among other things. Another aspect of the training, encouraging store leaders to create an environment where workers feel heard to avoid workers from unionizing, points to another positive externality of unionization efforts: that even places that don’t unionize improve their practices and give workers a greater voice to avoid the threat of unionization.

An opinion piece in the Guardian by Steven Greenhouse identifies a critical moment for American labor leaders to back independent unionization efforts throughout the country. The piece, titled, “The key to worker power in America? Let a thousand Chris Smalls bloom” argues that we are in “an unusually promising moment for labor,” not just because of the rise of labor organizing in general, but because of the rise in self-organizing. Chris Smalls is the prototypical example: Smalls was fired from Amazon after organizing against Amazon’s unsafe covid conditions, and then formed the Amazon Labor Union (ALU), which went on to win the first unionization drive at an Amazon facility in Staten Island. When the ALU organized, Amazon couldn’t call the union a group of outsiders like they had in Alabama—because the organizing was done from the ground up, by Amazon workers. But outside of rare occasions, such organizing efforts can be doomed to fail without having sufficient resources to take on big companies like Amazon and Starbucks, even just to have lawyers to file for union elections or fight back when companies illegally fire workers for organizing.

“Many labor leaders might hesitate to back today’s burst of self-organizing because they won’t control those efforts and won’t get the members and the dues money resulting from them,” Greenhouse writes. “But if labor leaders are serious about ending decades of decline and about strengthening unions to win a better deal for workers, they need to jettison their old-style thinking and provide money and lawyers to help today’s union surge grow and then grow some more. If they don’t do this, it will show that all their talk about reversing labor’s decline is empty rhetoric.”

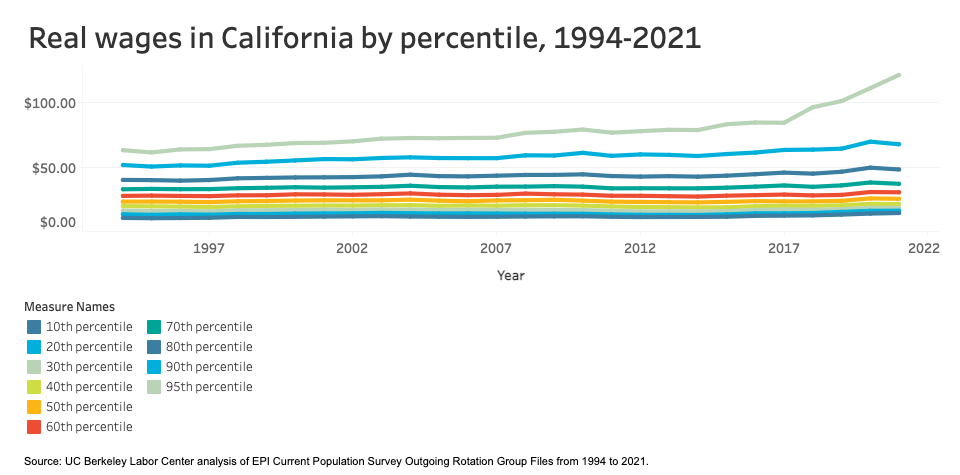

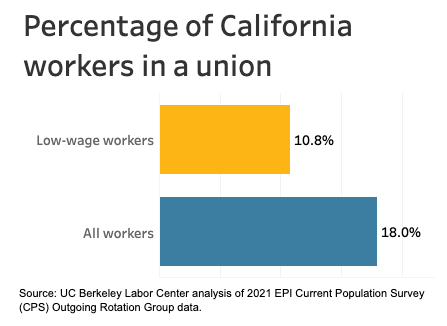

The UC Berkely Labor Center published an updated version of its Low-Wage Work in California Data Explorer. The Data Explorer contains a “wide range of data on California’s low-wage workers: numbers of workers, demographics, job quality, occupations, industries, economic security indicators, geography, and more.” The numbers show that one in three working Californians has a low-wage job, defined as jobs that pay less than $18.02 per hour—less than two-thirds of the median full-time wage in California. Low wage workers have seen much slower real wage growth than workers with higher wage earnings, despite increases in the state minimum wage. The data also shows that unionization rates for low-wage workers are disproportionately low. “As the state emerges from the pandemic, more needs to be done to ensure that workers who are paid low wages benefit from the economic recovery,” said Enrique Lopezlira, who directs the Low-Wage Work Program at the Labor Center. The data comes from various sources including the U.S. Bureau of Labor Statistics.

Some highlights:

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 27

The Ninth Circuit allows Trump to dismantle certain government unions based on national security concerns; and the DOL set to focus enforcement on firms with “outsized market power.”

February 26

Workplace AI regulations proposed in Michigan; en banc D.C. Circuit hears oral argument in CFPB case; white police officers sue Philadelphia over DEI policy.

February 25

OSHA workplace inspections significantly drop in 2025; the Court denies a petition for certiorari to review a Minnesota law banning mandatory anti-union meetings at work; and the Court declines two petitions to determine whether Air Force service members should receive backpay as a result of religious challenges to the now-revoked COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

February 24

In today’s news and commentary, the NLRB uses the Obama-era Browning-Ferris standard, a fired National Park ranger sues the Department of Interior and the National Park Service, the NLRB closes out Amazon’s labor dispute on Staten Island, and OIRA signals changes to the Biden-era independent contractor rule. The NLRB ruled that Browning-Ferris Industries jointly employed […]

February 23

In today’s news and commentary, the Trump administration proposes a rule limiting employment authorization for asylum seekers and Matt Bruenig introduces a new LLM tool analyzing employer rules under Stericycle. Law360 reports that the Trump administration proposed a rule on Friday that would change the employment authorization process for asylum seekers. Under the proposed rule, […]

February 22

A petition for certiorari in Bivens v. Zep, New York nurses end their historic six-week-strike, and Professor Block argues for just cause protections in New York City.