Maddie Chang is a student at Harvard Law School.

In today’s Tech@Work, Senate Democrats consider whether AI might help shorten the work week; and researchers find OpenAI’s GPT exhibits racial and gender bias when used to rank job applicants.

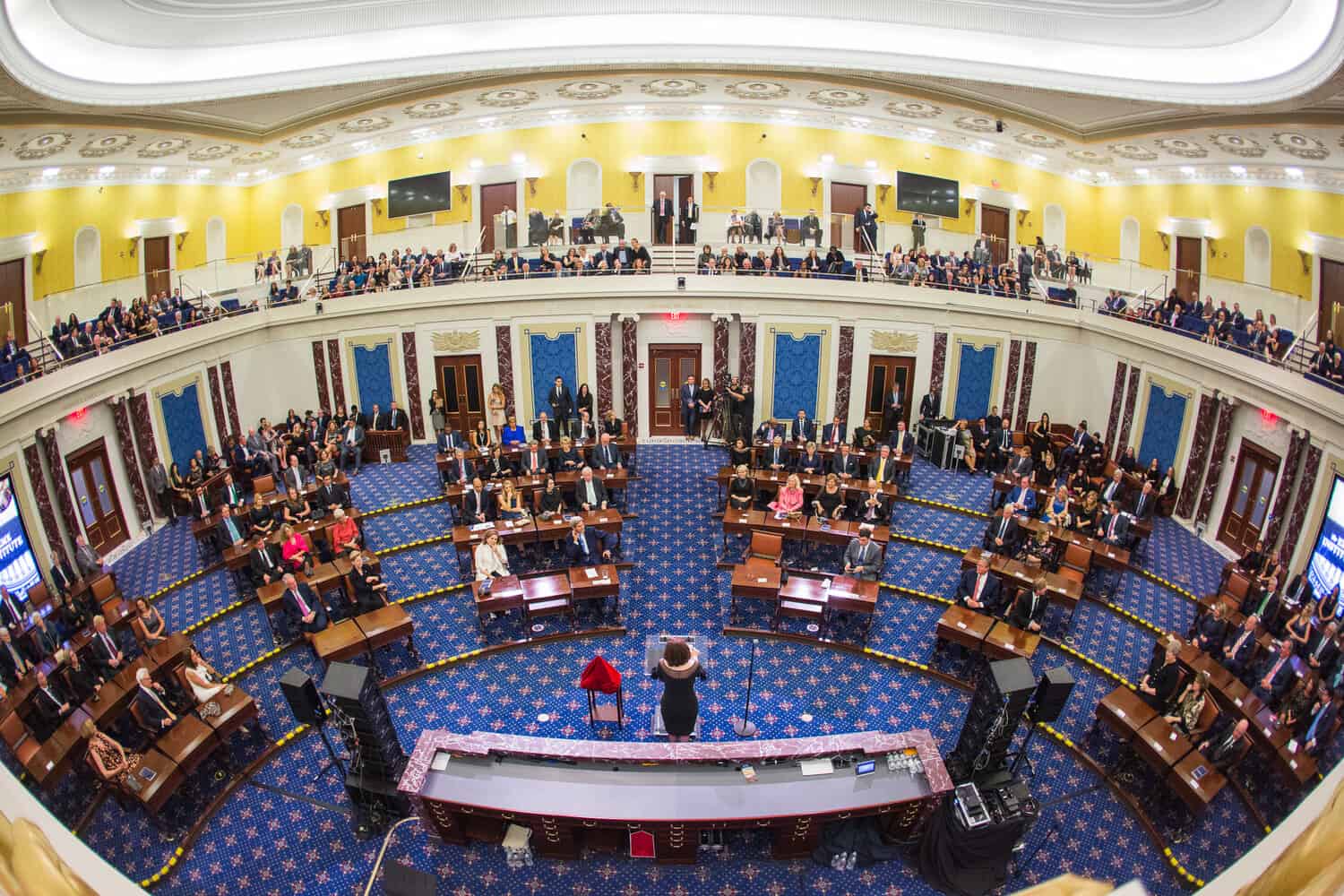

The Senate Committee on Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) held a hearing last week to explore the idea of a four day work week. Committee Chair Senator Bernie Sanders (I-Vt.) opened the hearing by noting that new technology like artificial intelligence makes workers more productive than ever before. He asked how the economic gains from that productivity will flow to workers. One possible route to shared benefit, he argued, is fewer working hours for the same pay, which may also increase worker productivity and lead to further gains.

Sen. Sanders and Senator Laphonza Butler (D-Calif.) introduced a bill to accomplish just that: it would reduce the Fair Labor Standards Act (FLSA)’s standard workweek from 40 to 32 hours by requiring that work beyond 32 hours per week be compensated as overtime. Senator Bill Cassidy (R-Louis.) expressed concern that a shorter workweek would add fuel to the inflation fire, passing costs to employers and hurting small businesses and retailers. At the hearing, Senators heard testimony from Boston College economist and sociology professor Dr. Juliet Schor whose research shows that a 32-hour workweek with no loss in pay leads to overall increases in productivity for companies because workers become more productive on an hourly basis – they are less stressed, happier and more efficient. Dr. Liberty Vittert, Professor of the Practice of Data Science Olin Business School, testified that the productivity gains of a four day workweek dissipate over time, and do not hold across all sectors. The committee also invited testimony from UAW International President Shawn Fain, Kickstarter’s Jon Leland (who has recently implemented the four day workweek), and Roger King of the HR Policy Association.

Last week, a team of reporters and researchers at Bloomberg tested the performance of OpenAI’s GPT for ranking job applicants and found worrying results. When fed names and resumes of fictitious job candidates for financial analyst and software engineer roles, GPT consistently down ranked candidates with names associated with Black Americans as compared to Asian, Hispanic and white counterparts. The experiment used an updated version of classic paired-test methodology to isolate the impact of race and gender on automated candidate ranking. The team began by generating eight different resumes with equal qualifications. They then randomly assigned “demographically-distinct” names to the resumes (names associated with Asian, Black, Hispanic and white men and women). Finally, researchers prompted GPT to rank the resumes for four different job postings, and ran the experiment 1,000 times. As they explain, “if GPT treated all the resumes equally, each of the eight demographic groups would be ranked as the top candidate one-eighth (12.5%) of the time.” But for the financial analyst and software engineer roles, Black Americans were disproportionately less likely to be ranked as top candidates. For example, “those with names distinct to Black women were top-ranked for a software engineering role only 11% of the time by GPT — 36% less frequently than the best-performing group.”

This degree of difference in outcomes meets the rule of thumb federal agencies use in findings of adverse impact, known as the four-fifths rule (when the selection rate for a given demographic group is less than 80 percent that of the best-treated demographic group – a threshold finding on the way to a potential overall finding of discrimination). Professor of Law at Emory Law School Dr. Ifeoma Ajunwa explains the background reason for this adverse impact: “The fact that GPT is matching historical patterns, rather than predicting new information, means that it is poised to essentially reflect what we already see in our workplaces. And that means replicating any historical biases that might already be embedded in the workplace.”

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

In Today’s News and Commentary, the Supreme Court green-lights mass firings of federal workers, the Agricultural Secretary suggests Medicaid recipients can replace deported farm workers, and DHS ends Temporary Protected Status for Hondurans and Nicaraguans. In an 8-1 emergency docket decision released yesterday afternoon, the Supreme Court lifted an injunction by U.S. District Judge Susan […]

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.