Catherine Ordoñez is a student at Harvard Law School.

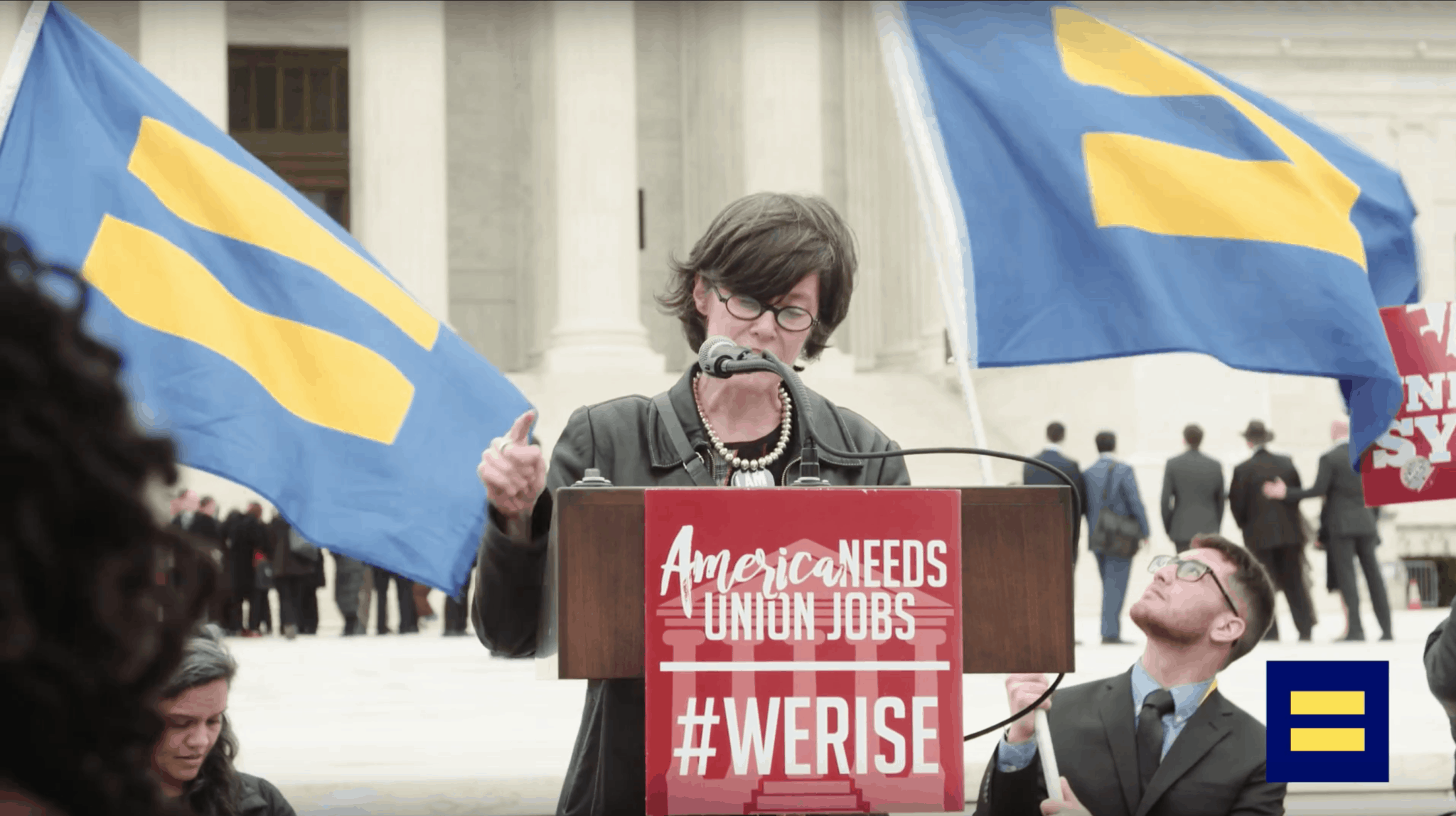

A coalition of six organizations committed to eliminating discrimination against LGBT individuals in the workplace filed an amicus brief in support of the respondents in Janus.

Miriam Frank—teacher, feminist, and author of Out In the Union: A Labor History of Queer America—said this brief marks the first time that a coalition of LGBT rights organizations has joined a non-marriage case at the Supreme Court as amici curiae. Departing from previous tradition of signing onto amicus briefs with other liberal organizations not focused on gay rights, these groups announced they are friends of the court in Janus as a queer community in particular because gay rights are baked into union policies. “AFSCME must be defended from the point of view of LGBT individuals because AFSCME and unions in the U.S. have been defending gay rights in the work place since the 1970s,” Frank said. “Unions have given our community dignity and a way to make a living. We want to show how that has been part of the labor unions that Mr. Janus is trying to destroy.”

The brief argues that the question presented in Janus is critical to eliminating workplace discrimination against LGBT people because fair-share fees fund union efforts to secure protections for LGBT workers. Although the brief noted that the question in Janus is critical, the brief does not discuss the legal issues in the case. Instead, the brief sets out to educate the Court on the “important role that secure, fee-supported unions have played in securing equal treatment for LGBT workers” so that the Court “understands the full scope of what is at stake in the case at bar.” This historical rather than legal analysis may resonate importantly with Justice Kennedy, whose majority opinions in Windsor and Obergefell are referenced in the brief.

The brief establishes first that LGBT workers, including public employees, suffer from workplace discrimination. This discrimination includes pay disparities, verbal and physical harassment, and termination. The brief cites various studies to illustrate the following about sexual orientation-based or gender identity-based discrimination suffered by LGBT workers:

- Gay male employees are paid up to 32% less on average than straight male coworkers, and lesbian workers earn less than both gay and straight men;

- In the public sector, LGB-identified employees earn 8 to 29 percent less than their straight counterparts;

- A quarter of LGB-identified and government-employed survey respondents reported experiencing employment discrimination because of sexual orientation in the past five years;

- Harassment, followed by termination, is the most frequently reported form of discrimination by LGB-identified individuals who are open about their sexual orientation at work;

- Transgender workers report unemployment at twice the rate of the general population; and

- 78% of trans individuals reported having experienced workplace discrimination related to their gender identity.

The brief demonstrates the verbal harassment and physical violence suffered by LGBT workers in the public sector, and notes that this discrimination negatively affects the mental and physical health of LGBT workers:

A gay employee of the Connecticut State Maintenance Department was tied up by his hands and feet; a firefighter in California had urine put in her mouthwash; a transgender corrections officer in New Hampshire was slammed into a concrete wall; and a transgender librarian at a college in Oklahoma had a flyer circulated about her declaring that God wanted her to die (internal citation omitted).

After establishing the prevalence of workplace discrimination against LGBT people, the brief transitions to discussing the power and practice of unions to protect LGBT workers from discrimination.

The brief presents a rich history of the ways that unions pioneered protections for LGBT workers, relying heavily on history detailed in Frank’s book Out In the Union. For example: In 1974, two American Federation of State, County and Municipal Employees (AFSCME) local unions negotiated collective bargaining agreements that expressly prohibited discrimination based on sexual orientation. In 1982, the staff union at the Village Voice in New York City “paved the way for modern domestic partner benefits” when it negotiated an extension of the company health plan to “spouse equivalents.” In the mid-1980s, the Columbia clerical local union collectively bargained for nondiscrimination protection for LGBT workers, spousal equivalent bereavement leave, health coverage, and tuition benefits for domestic partners. And that same decade, the Amalgamated Clothing and Textile Workers Union negotiated the addition of “change of sex” to the list of protected classes at an industrial laundry facility after a union steward was harassed at work following her gender reassignment surgery.

The brief highlights how unions prevent and remedy discrimination against LGBT workers through collective bargaining. To start, the brief asserts that collective bargaining allows the contractual creation and enforcement of workers’ rights that exist independent of any state or federal law. As a result, CBAs that include a ban on sexual orientation discrimination or gender identity discrimination provide independent protection from discrimination for all LGBT workers covered by these agreements. This protection is particularly important for workers in states that do not prohibit discrimination on those bases under state law. As evidence that unions pursue these contractual protections in CBAs, the brief provides that greater than 1,700 AFSCME union contracts include sexual orientation as part of a nondiscrimination clause, and many also include language prohibiting discrimination on the basis of gender identity.

Antidiscrimination provisions in CBAs, according to the brief, protect LGBT workers by measurably deterring discrimination—“research suggests that LGBT employees experience less discrimination when their employer has a nondiscrimination policy that includes sexual orientation and gender identity”—and allowing workers to invoke union grievance procedures to address and resolve violations. The brief argues that these grievance procedures are good for aggrieved employees, taxpayers, and the judicial system, as they provide an efficient and cost-effective way to resolve employment disputes at no cost to the individual employee and without any court involvement.

The brief, which was submitted on behalf of Human Rights Campaign, Lambda Legal Defense and Education Fund, the National Center for Lesbian Rights, the National LGBTQ Task Force, and PFLAG National, can be found here.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 26

Starbucks and Workers United resume bargaining talks; Amazon is ordered to disclose records; Alabamians support UAW’s unionization efforts.

April 25

FTC bans noncompete agreements; DOL increases overtime pay eligibility; and Labor Caucus urges JetBlue remain neutral to unionization efforts.

April 24

Workers in Montreal organize the first Amazon warehouse union in Canada and Fordham Graduate Student Workers reach a tentative agreement with the university.

April 23

Supreme Court hears cases about 10(j) injunctions and forced arbitration; workers increasingly strike before earning first union contract

April 22

DOL and EEOC beat the buzzer; Striking journalists get big NLRB news

April 21

Historic unionization at Volkswagen's Chattanooga plant; DOL cracks down on child labor; NY passes tax credit for journalists' salaries.