Ariel Boone is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

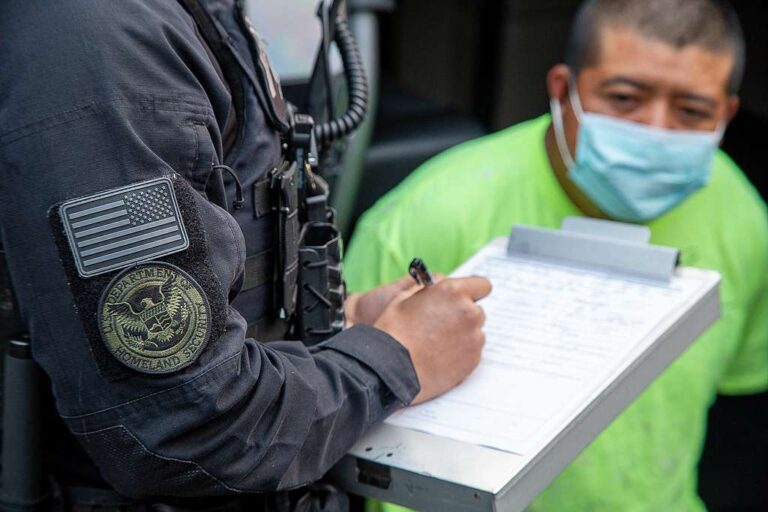

On January 20, 2025, the Trump administration rescinded a longstanding policy which previously protected “sensitive” areas like hospitals and clinics from immigration enforcement. Stripped of these protections, healthcare workers and noncitizen patients now face escalating intrusions by federal agents. Masked ICE agents are entering hospitals and clinics, refusing to show identification, surveilling patients, and stopping workers from doing their jobs. These workplace confrontations raise questions about federal law governing ICE presence in private healthcare settings, what Congress can do to protect workers and patients, and the ways workers are acting through their unions to protect themselves and their patients within the bounds of the law.

ICE’s Destructive Presence in Hospitals

In July, federal immigration agents “camped out” for 15 days at Glendale Memorial Hospital, a private facility in Southern California, after a woman arrested by ICE needed emergency medical care. According to the California Nurses Association, ICE “remov[ed] the patient from the side door apparently against the medical advice of the patient’s physician.” She was then transferred to another hospital, where ICE reportedly surveilled her, denied her visitors, and prevented her from speaking privately with her doctors.

Sometimes ICE enters a hospital or clinic to arrest a patient inside. Other times, they arrive at the hospital with a noncitizen who had a medical emergency during an arrest, or they follow someone known to be undocumented into the hospital, targeting them for arrest.

Workers have a stake in deciding what happens when immigration agents appear and how employers respond. Agents’ presence can interfere with healthcare delivery — as when an ICE agent reportedly physically blocked a UCLA nurse from caring for a screaming woman on a gurney. Such intrusion jeopardizes patient privacy and may measurably discourage patients from seeking care. Moreover, tensions with ICE can create a hostile environment for healthcare workers and expose them to stress and legal liability. A California Nurses Association leader told outlet CalMatters that ICE enforcement left Bay Area hospital staff “emotionally and physically upset.”

Current Law on Warrants, Access, and Interacting with ICE

Federal law puts workers in a bind when protecting themselves or patients: It requires ICE to have a warrant to enter private patient areas, but criminalizes interfering with agents’ duties.

At issue in healthcare facilities is where ICE is allowed to be. Federal law theoretically disallows ICE from entering private patient care areas closed to the general public without a valid warrant signed by a federal judge. (An administrative warrant is not sufficient.) But agents do not need warrants to enter hospital lobbies or waiting areas. Guidance from the ACLU advises that health centers must generally “allow ICE agents in any areas where they would allow general members of the public.” This public/private area distinction has spurred some workers and businesses to post signs identifying private areas as such.

Nevertheless, asking for a warrant can elicit a negative reaction from ICE. In October, ICE agents handcuffed a Chicago alderperson at an emergency room after the alderperson asked for their warrant to detain a patient. And, ICE agents have insisted on entering private patient areas without a warrant anyway, as occurred at UCLA.

Confronting ICE can expose workers to criminal consequences. Healthcare workers asserting patients’ rights risk running afoul of federal criminal code 18 U.S.C. § 111, which prohibits forcibly assaulting, resisting, impeding, or interfering with a federal officer’s duties, and 8 U.S.C. § 1324(a), which prohibits “harboring” or helping to conceal someone without lawful immigration status. In July, federal agents chased a man into a Southern California surgical center. In a dramatic video, workers asked an agent for identification and a warrant and demanded he leave, noting they were on private property. The workers were accused of impeding the operation and charged by a grand jury with misdemeanor assault on a federal officer.

To address these scenarios, Congress could codify protections for hospitals. In 2021, the Biden administration expanded a list of sensitive areas off-limits to immigration enforcement to include hospitals and healthcare facilities, schools, and places of worship. In February of 2025, several House Democrats introduced the “Protecting Sensitive Locations Act” to make the Biden policy permanent and prevent enforcement within 1,000 feet of such areas. With Democrats in the minority, the bill is stalled. States can also take action to instruct non-federal actors on how to interact with immigration agents or direct attorneys general to develop guidelines, but states cannot contravene federal law.

The Role of Unions

Handling legal rights in the healthcare workplace is tricky. For example, workers may want to assert the warrant requirement if ICE seeks entry to a private area, or designate a site representative to speak with ICE and examine warrants. These responses require advance training and guidance. Understandably, many workers are working within their unions to call on employers to issue clear guidance on how to lawfully protect workers and patients if ICE arrives.

Many nurses’ unions are speaking out about ICE’s entries into hospitals. The Massachusetts Nurses Association, Washington State Nurses Association, and Ohio Nurses Association have all issued advice and guidance to members about how to respond to ICE in the workplace. National Nurses United, SEIU-UHW, and the New York State Nurses Association have issued statements condemning the Trump administration’s immigration enforcement intrusions in healthcare workplaces. Workers are also hosting impromptu and independent meetings to make safety plans.

SEIU-UHW published model policies for responding to immigration enforcement. These include limiting the collection of patients’ immigration information, understanding ICE warrants, and verifying identities of purported federal agents. Above all, they demand employers have explicit training and policies in place to address intrusions by ICE.

Response to ICE presence could easily be considered a mandatory subject of bargaining addressing health and safety in the workplace, given the trauma, physical danger, and criminal liability that it can pose. Workers can demand the development of emergency response policies, additional signage identifying “private” areas off-limits to unwarranted access, and training for staff.

Workers may also bargain on “permissive” topics by bargaining for the common good, a strategy to prioritize community demands and well-being at the negotiating table. Permissive topics are by definition non-mandatory. But workers could demand that where allowed by state and federal law, their employers collect minimal information on patients’ immigration status. Workers can also call on hospitals to guarantee continued family visitation and communications rights for patients brought in by ICE, or ensure workers can inform patients of legal rights during patient visits without retaliation.

Still, reaching a new contract can take years, and immigration enforcement is escalating now. Outside of contract bargaining, workers can create emergency plans, assert the rights of their patients, film ICE, or call local immigration defense hotlines to report sightings of agents. All of these activities may arguably fall under Section 7 of the NLRA as “concerted activities” for employees’ “mutual aid and protection,” protected from employer retaliation.

Under these many approaches, advocates see one goal: A safe workplace for healthcare workers and protection for all patients seeking care, regardless of immigration status.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 27

The Ninth Circuit allows Trump to dismantle certain government unions based on national security concerns; and the DOL set to focus enforcement on firms with “outsized market power.”

February 26

Workplace AI regulations proposed in Michigan; en banc D.C. Circuit hears oral argument in CFPB case; white police officers sue Philadelphia over DEI policy.

February 25

OSHA workplace inspections significantly drop in 2025; the Court denies a petition for certiorari to review a Minnesota law banning mandatory anti-union meetings at work; and the Court declines two petitions to determine whether Air Force service members should receive backpay as a result of religious challenges to the now-revoked COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

February 24

In today’s news and commentary, the NLRB uses the Obama-era Browning-Ferris standard, a fired National Park ranger sues the Department of Interior and the National Park Service, the NLRB closes out Amazon’s labor dispute on Staten Island, and OIRA signals changes to the Biden-era independent contractor rule. The NLRB ruled that Browning-Ferris Industries jointly employed […]

February 23

In today’s news and commentary, the Trump administration proposes a rule limiting employment authorization for asylum seekers and Matt Bruenig introduces a new LLM tool analyzing employer rules under Stericycle. Law360 reports that the Trump administration proposed a rule on Friday that would change the employment authorization process for asylum seekers. Under the proposed rule, […]

February 22

A petition for certiorari in Bivens v. Zep, New York nurses end their historic six-week-strike, and Professor Block argues for just cause protections in New York City.