Ian Kalil is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

Bargaining for the common good sprang up in the vernacular of labor organizing in the wake of the Great Recession. Common good bargaining is a practice by which a bargaining unit uses its negotiating power to make demands that benefit parties not formally at the negotiating table, often the community which the bargaining unit serves. For example, the National Education Association defines bargaining for the common good as “an innovative bargaining strategy where educators and their unions join together with parents and other stakeholders to demand change that benefits educators, students, and the community as a whole.” As the Bargaining for the Common Good organization describes, common good demands “move beyond ‘bread and butter’ issues like pay and benefits.”

In a recent example, teachers in Oakland made national news when they went on strike demanding implementation of the district’s Reparations for Black Students policy, expedited Section 8 housing vouchers for unhoused families in the district, and expanded transportation for students. In another example from 2019, Health Professionals and Allied Employees, the largest union of registered nurses and healthcare professionals in New Jersey, demanded that hospitals not sell any of their patients’ medical debt to third-party debt-collection agencies.

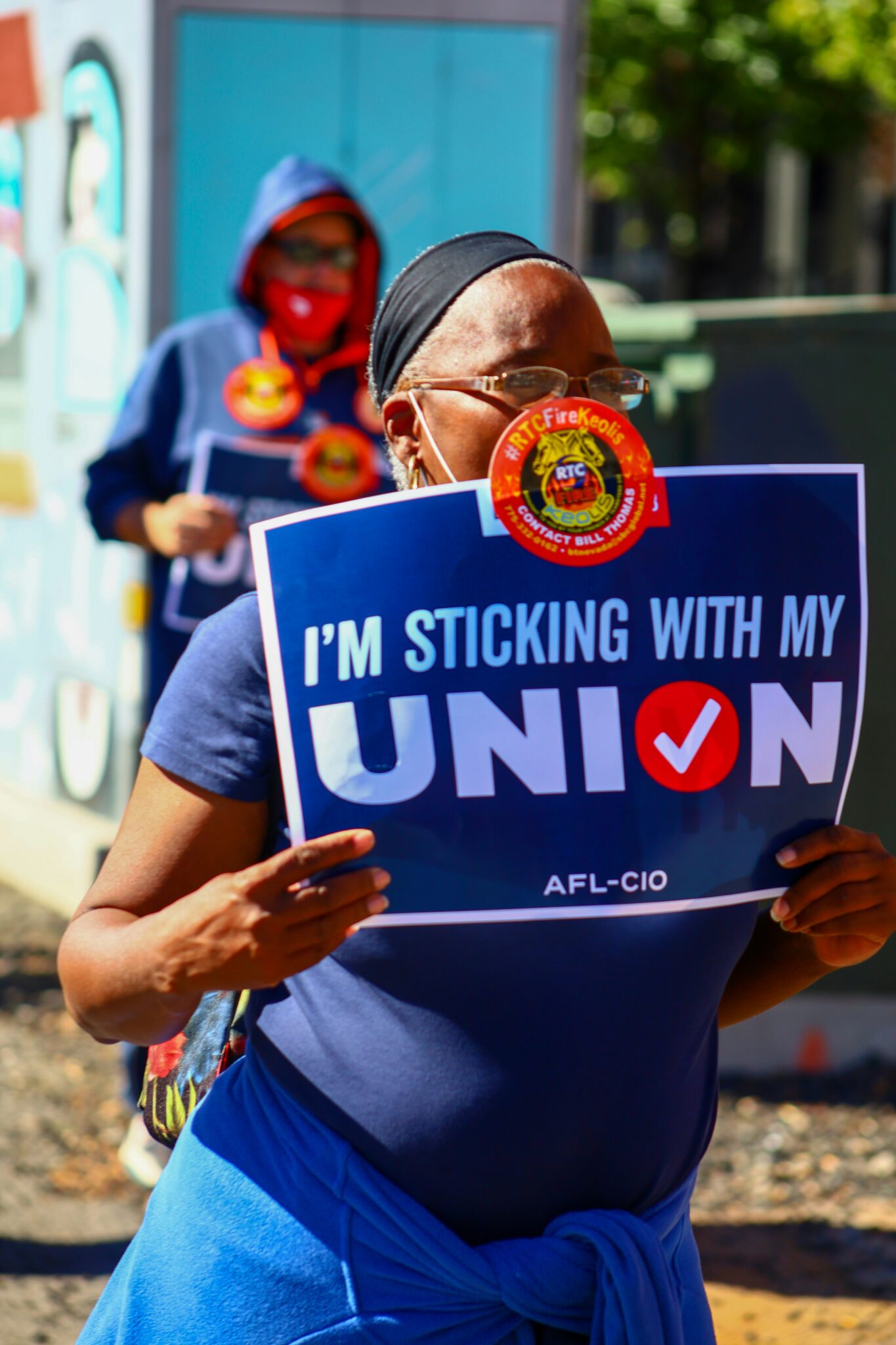

While the push to use collective bargaining power to advance demands that address issues like racial justice, climate justice, housing, and many other structural and societal issues is positive, bargaining for the common good need not be cast in contrast to “traditional” collective bargaining. For example, supporters of bargaining for the common good point out that the resurgence of public support for unions has been aided by unions’ incorporation of common good demands. But it is important that public support for unions stays strong even when unions engage in traditional bargaining for better wages and working conditions. A brief look at the history of labor organizing in the U.S. and economic research reveals that bargaining over those “bread and butter” issues contributes to the common good as well. Support that unions are receiving as a result of common good bargaining should extend to their traditional bargaining efforts.

The Five Day, 40-Hour Work Week

For an example of how the efforts of organized workers to improve their own working conditions can produce widespread benefit, one need look no further than the history of the eight-hour workday in America. In the wake of the American revolution and again in 1835, Philadelphia carpenters went on strike for a shorter, ten hour work day. Unions began demanding an eight-hour workday at least as early as 1866, when the first national labor group in the United States, the National Labor Union, called for Congress to mandate an eight-hour workday. In the absence of federal action, the Illinois state legislature mandated an eight-hour workday in 1867.

Through the close of the 19th century, unions and labor organizations continued to push for an eight-hour workday: “Eight Hour Leagues” formed, workers organized parades and mass meetings, and workers continued to strike. These efforts culminated in a strike of more than 30,000 Chicago workers on May 1st, 1886. The violence that erupted in the subsequent “Haymarket Incident” briefly chilled the movement but did not stop it. Union demands made it into the progressive campaign of Teddy Roosevelt resulting in the passage of the Adamson Act which mandated an eight hour workday for railroad workers. Finally, decades of union pressure and the Great Depression’s severe unemployment culminated in the Fair Labor Standards Act, establishing an eight-hour day and forty-hour work week for union and non-union workers alike.

We may see this particular common good effect of union bargaining again in the near future. In their recent strikes, the United Auto Workers demanded a 32-hour, 4-day work week. While this demand was not included in any of the tentative agreements reached by UAW and the Big Three, it might mark the beginning of an effort that will ultimately redefine the work week in America.

The Spillover Effects of Wage Bargaining

It is important to recognize that “traditional bargaining,” bargaining for increased wages and better working conditions, can itself be considered a common good in at least two ways. First, as Professor Diana Reddy writes, “Under the demand-side Keynesian view, higher wages for workers grew the economy for all.” In this view, worker bargaining for increased wages can be bargaining for the common good, as higher wages means greater consumer demand which can translate into greater economic activity. Though critics argue that higher wages are generally passed on to consumers in the form of higher prices, this need not necessarily be so. For example, during the 1945 – 46 United Auto Workers strike against General Motors, the UAW demanded pay increases but also demanded that GM not pass along the cost of the increases to consumers by raising car prices. When GM countered with a significant lower wage increase, the UAW demanded that GM open its books and prove its inability to pay. GM refused, calling the demands “un-American and socialist.” Although ultimately the UAW settled for a lower wage increase, and GM did not have to give up its control over product pricing, this history shows a viable approach to common good wage bargaining.

Second, when unions bargain for wage increases and better working conditions, this often has spillover effects on non-union workers’ wages and working conditions. Where unions have negotiated better contracts for their members, non-union employers often raise wages or offer similar benefits to attract workers and/or to discourage its own employees from unionizing. This is the so-called threat effect. A recent report from the U.S. Department of Treasury confirmed that these spillovers exist: “Each 1 percentage point increase in private-sector union membership rates translates to about a 0.3 percent increase in nonunion wages. These estimates are larger for workers without a college degree…”

Why It Matters

When workers demand higher wages, they often face the criticism that they are acting selfishly. When workers make “common good” demands that would impact the larger community, critics tell them that they have “gone too far.” In reality, union bargaining has positively impacted union and non-union workers alike, and unions have been making demands for the common good since their inception. Acknowledging this history is an important step towards strengthening public support for unions and collective bargaining.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 15

The Department of Labor announces new guidance around Occupational Safety and Health Administration penalty and debt collection procedures; a Cornell University graduate student challenges graduate student employee-status under the National Labor Relations Act; the Supreme Court clears the way for the Trump administration to move forward with a significant staff reduction at the Department of Education.

July 14

More circuits weigh in on two-step certification; Uber challengers Seattle deactivation ordinance.

July 13

APWU and USPS ratify a new contract, ICE barred from racial profiling in Los Angeles, and the fight continues over the dismantling of NIOSH

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

the Supreme Court allows Trump to proceed with mass firings; Secretary of Agriculture suggests Medicaid recipients replace deported migrant farmworkers; DHS ends TPS for Nicaragua and Honduras