Ryan Zhang is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

For decades, political scientists have documented a stark reality: Economically marginalized Americans struggle to exert meaningful influence over public policy. Studies show that the preferences of low- and middle-income constituents exert “little or no independent influence” on federal decision-making, while elected officials give “no weight” to the views of constituents in the bottom third of the income distribution. The same holds true at the state level, where low-income citizens’ impact on state policy is “indistinguishable from zero.” Crucially, these patterns have persisted through the Trump era. Despite populist rhetoric, the administration’s major policy initiatives, from tax cuts to health and safety-net rollbacks, have served the interests of the affluent rather than the working class. This democratic deficit has many causes, but one overlooked factor is structural. Redistricting, or the process by which legislative districts are drawn, can serve as a tool to improve political responsiveness to working-class communities. By drawing maps that preserve, rather than splinter, these communities, states can ensure that they have the ability to elect their preferred representatives and have a stronger voice in shaping the laws by which they are governed.

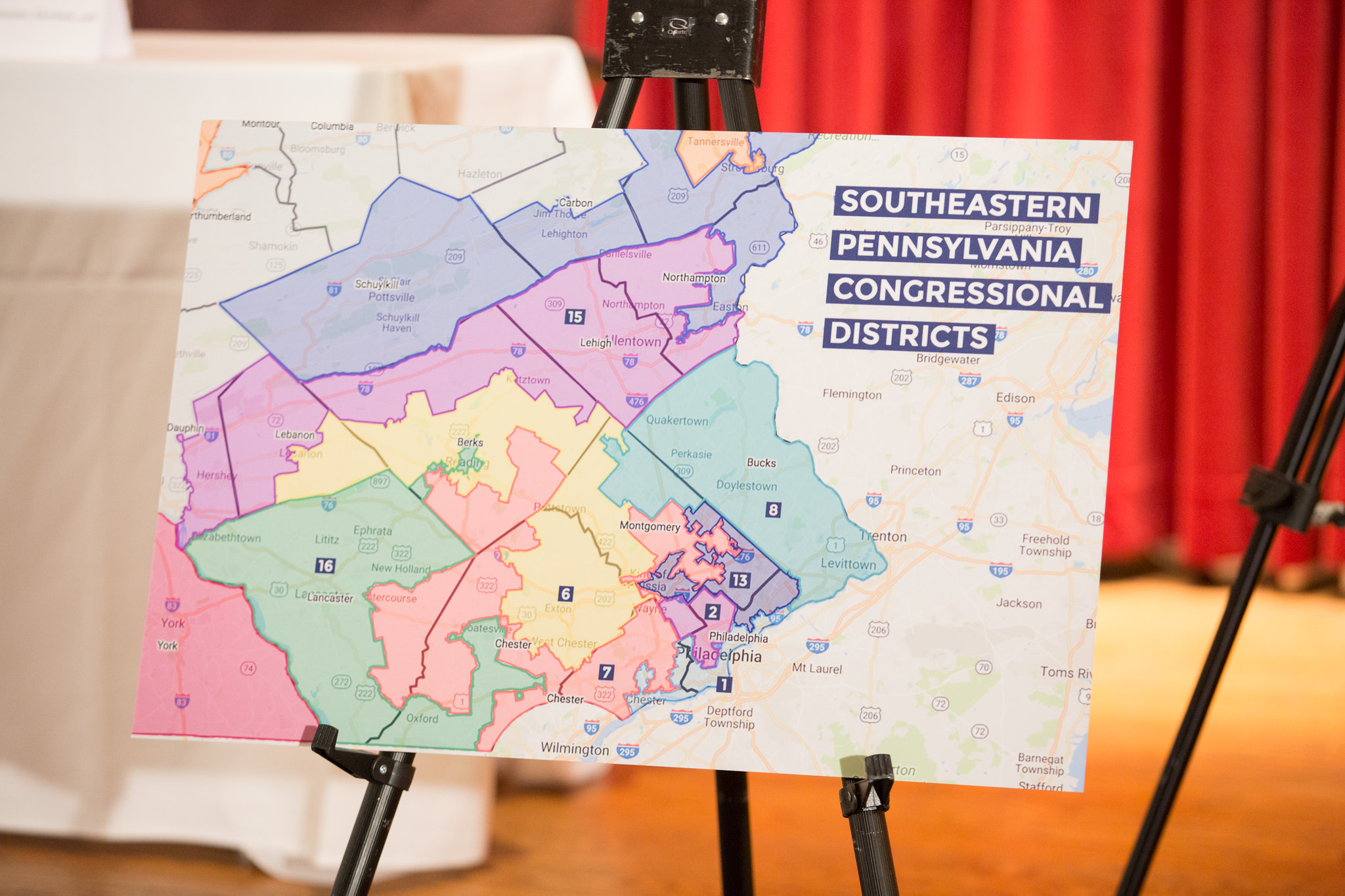

District lines play a central role in determining whether low-income voters have a political voice. In a single-member district system, as most U.S. jurisdictions use, being a sufficiently large share of a district is what determines whether a community can elect a representative who is responsive to its needs. As civic engagement groups like Common Cause note, redistricting determines who is elected and, thus, how responsive public policy will be to working-class communities for the next decade. A community kept intact can more effectively “elect candidates of choice and keep elected officials accountable,” while fractured communities lose their political power and with it a platform to voice their needs.

Map drawers, however, can easily manipulate whether a group forms a majority. One common tactic is “cracking,” or splitting a cohesive community across multiple districts so that it is too small in each to elect its preferred candidate. For working-class communities, cracking occurs by folding low-income neighborhoods into wealthier districts, where their preferences are overshadowed as officials prioritize the concerns of higher-income, higher-turnout voters who wieldgreater political influence. Ensuring that economically disadvantaged neighborhoods form a meaningful share of a district—large enough to give them a realistic opportunity to elect their preferred candidate—can help concentrate their voting power behind a representative more attuned to their needs.

Oakland illustrates how district lines can systematically mute the voices of working-class communities. For decades, Oakland’s city council districts zigzagged across the city’s geography, intentionally combining working-class “flatland” neighborhoods with affluent hill communities. The stated rationale was to ensure that “the interests of both [communities] would be addressed,” but the true effect was to “dilute the voices of low-income people.” Community coalitions noted that these gerrymandered lines split cohesive neighborhoods like Chinatown and Maxwell Park, while producing hill-area majorities in multiple districts, leaving flatland communities with little ability to elect representatives responsive to their needs. The result was chronic underrepresentation on issues that disproportionately affected low-income residents, including “transportation, school resources, and delivery of city services.”

Empirical research shows that drawing economically coherent districts can meaningfully improve responsiveness to working-class voters. Work by Christopher Ellis and Kristina Miler finds that representatives from districts with working-class constituencies are more attentive to poverty-related issues, introduce more legislation addressing economic inequality, and devote greater attention to concerns such as wages, housing, and social services. Evidence at the local government level similarly shows that when disadvantaged neighborhoods are placed in their own districts, their representatives devote more attention to the provision of basic services. Together, this research demonstrates that when working-class communities are kept intact rather than splintered, their political preferences register more clearly and loudly, such that elected officials become meaningfully more responsive to their concerns.

But if districts with working-class majorities produce more responsive representation, then redistricting rules must be designed to make such districts possible. Many states already use a tool that serves this purpose: the “community of interest” (COI) criterion, which instructs map drawers to keep intact groups of residents whose shared circumstances make cohesive representation especially important. Although often discussed in racial, ethnic, or cultural terms, COIs can also reflect socioeconomic realities, such as neighborhoods linked by similar income levels.

The challenge, however, remains in coverage. Only about half of states require map drawers to consider COIs. Michigan, for instance, requires the preservation of COIs defined by “share[d] cultural or historical characteristics or economic interests,” while Kansas directs mapmakers to consider “social, cultural, racial, ethnic, and economic interests common to the population.” These provisions reflect an understanding that preserving economically coherent communities, including working-class communities, strengthens democratic representation and responsiveness. Yet without wider adoption, many communities remain vulnerable to being cracked apart.

Looking forward, all states should adopt clear, enforceable COI criteria. States can begin by explicitly recognizing shared economic conditions, employment patterns, and industry-based ties as legitimate COI factors. States should ensure that these protections apply to not only congressional maps but also state legislative districts. Many of the policies most directly shaping economic opportunity, whether the minimum wage or housing policy, are made at the state level, making state-level COI protections essential. Alternatively, though politically unlikely, the most effective solution would be for Congress to adopt a federal COI mandate under its Elections Clause authority, ensuring that working-class communities receive nationwide protection. And ultimately, to guard against manipulation, districts should be drawn by independent redistricting commissions rather than partisan legislatures.

Of course, redistricting is not a panacea. Even if working-class Americans are better able to elect their preferred representatives, redistricting can counterbalance neither the influence of money in politics, including the influence corporations wield through lobbying and campaign spending, nor other structural barriers that impede working-class political power, such as chronically low voter turnout driven by demanding work schedules, unstable housing, and limited access to transportation. Nevertheless, economic COIs give low-income communities a baseline, making their votes and priorities harder for elected officials to ignore.

For decades, working-class Americans have struggled with persistent economic hardship and a political system unattuned to their needs. Poverty remains stubbornly high, and socioeconomic mobility has stagnated, while the most affluent Americans have benefited from concentrated income and wealth growth. Reforming redistricting to ensure that working-class communities can elect their preferred representatives would strengthen their political voice and improve responsiveness, laying the groundwork for more equitable policymaking.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

January 28

Over 15,000 New York City nurses continue to strike with support from Mayor Mamdani; a judge grants a preliminary injunction that prevents DHS from ending family reunification parole programs for thousands of family members of U.S. citizens and green-card holders; and decisions in SDNY address whether employees may receive accommodations for telework due to potential exposure to COVID-19 when essential functions cannot be completed at home.

January 27

NYC's new delivery-app tipping law takes effect; 31,000 Kaiser Permanente nurses and healthcare workers go on strike; the NJ Appellate Division revives Atlantic City casino workers’ lawsuit challenging the state’s casino smoking exemption.

January 26

Unions mourn Alex Pretti, EEOC concentrates power, courts decide reach of EFAA.

January 25

Uber and Lyft face class actions against “women preference” matching, Virginia home healthcare workers push for a collective bargaining bill, and the NLRB launches a new intake protocol.

January 22

Hyundai’s labor union warns against the introduction of humanoid robots; Oregon and California trades unions take different paths to advocate for union jobs.

January 20

In today’s news and commentary, SEIU advocates for a wealth tax, the DOL gets a budget increase, and the NLRB struggles with its workforce. The SEIU United Healthcare Workers West is advancing a California ballot initiative to impose a one-time 5% tax on personal wealth above $1 billion, aiming to raise funds for the state’s […]