Tascha Shahriari-Parsa is a student at Harvard Law School.

In today’s news and commentary: budget reconciliation deal excludes fines for labor law violations; the first union at Trader Joe’s; and the Third Circuit’s blow to unions and other advocacy groups.

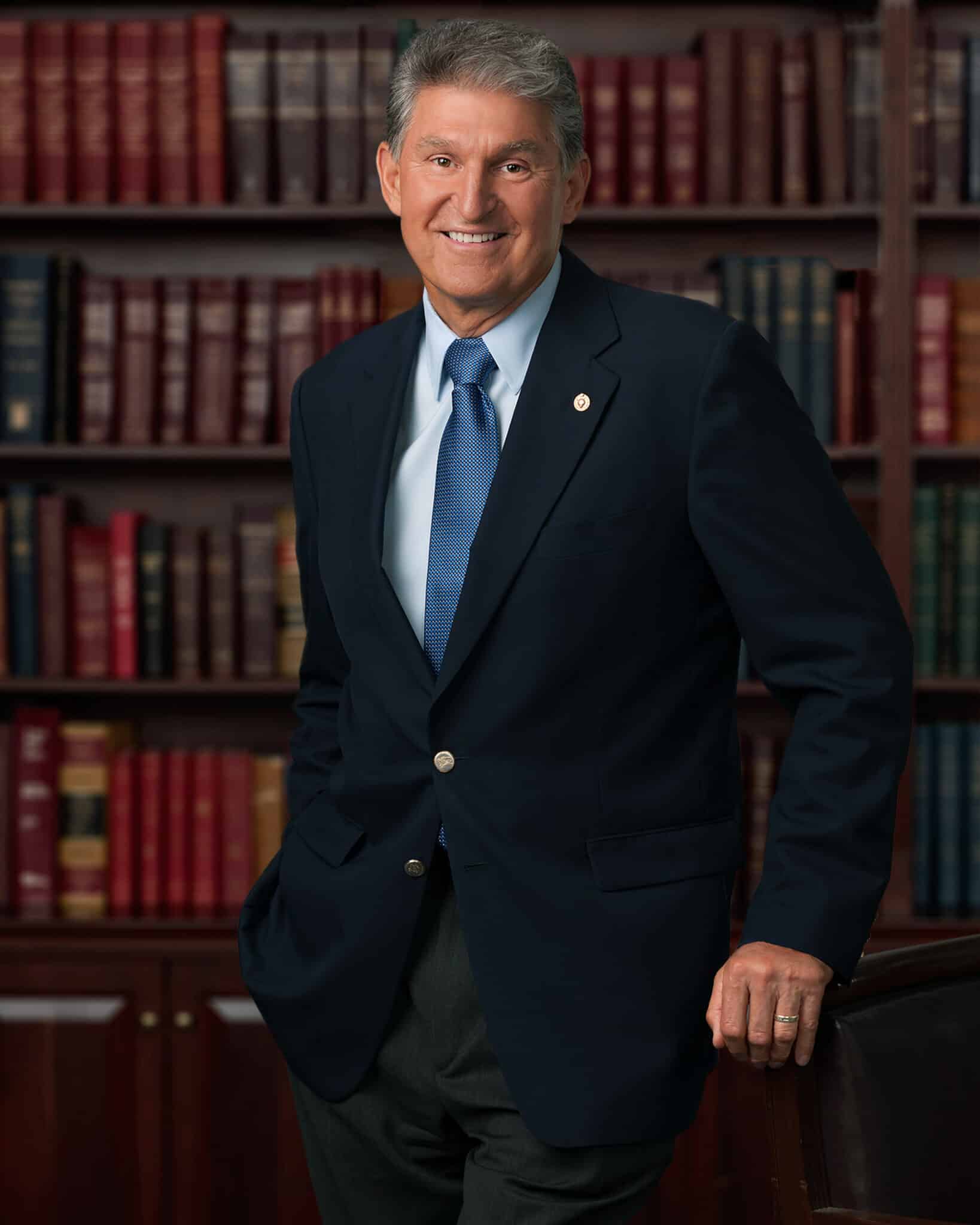

This week, as Senate Majority Leader Chuck Schumer (D-NY) reached a deal with Senator Joe Manchin (D-WV) for legislation to pass through budget reconciliation, the package contained a consequential omission: civil penalties for labor law violations. As Ben, Maxwell and I wrote for the blog last July: “If enacted, a new monetary penalties regime would mark the most significant, pro-worker reform of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) since the Act’s passage in 1935 and could significantly boost workers’ ability to address violations of their right to organize.” Earlier drafts of the reconciliation bill contained civil penalties provisions as well as increased funding for the NLRB, though the latter was removed from the proposed bill in March.

Former two-term NLRB member Mark Gaston Pearce, now the executive director of the Workers’ Rights Institute at Georgetown University Law Center, called the scrapping of civil penalties from the bill “another outrageous turn of the knife to an agency principally responsible for enforcing the primary labor law in this country.” After decades of labor law’s ossification, empowering the NLRB to impose fines for Unfair Labor Practices is the least that Congress can do to effectuate the NLRA’s commands—to address the “inequality of bargaining power” between employees and employers.

Just as the draft bill was previously amended to remove the provisions, the provisions can just as easily be added in again in negotiations with Manchin. Additionally, once the bill reaches the Senate floor, any Senator can motion to amend the bill during what has been termed the “vote-a-rama” of the budget reconciliation process.

A Trader Joes store in Western Massachusetts was the first to unionize on Thursday. Workers at the store in the city of Hadley voted 45-31 in favor of unionizing. “Our contract will not just benefit us,” Trader Joe’s United said in a statement. “We believe that our union, by improving our store and every store across the country, will strengthen Trader Joe’s as a whole and help the company return to its core values.”

On Thursday, the Third Circuit ruled that a jury could reasonably find that SEIU affiliates representing nursing home workers committed extortion under the Racketeer Influenced and Corrupt Organizations (RICO) Act. The case, Care One Management v. United Healthcare Workers East, could have lasting implications and chilling effects for union organizing, collective bargaining, and even broader advocacy efforts by non-profit groups.

Care One sued SEIU affiliates in court alleging both mail and wire fraud, as well as extortion, under RICO. After an appeal by Care One from a District Court decision granting summary judgment to the Unions, the Third Circuit first affirmed the District Court on all grounds. Care One appealed again, and on re-hearing, the same Third Circuit panel modified its previous holding and determined that the District Court erred in granting summary judgment to the Unions on the question of extortion.

In arguing that the Unions committed extortion, Care One characterized the Unions’ actions as amounting to both sabotage and fear of economic loss. The night before the Unions planned to strike, the Care One facilities in Connecticut were vandalized, medical records were altered, and other similar acts of sabotage were committed. Although there was no evidence that the Unions had authorized these acts—and if anything, ample evidence that they affirmatively rebuked it—on rehearing, the Third Circuit agreed that a jury could find that the Unions—not just union members—committed sabotage.

In supporting its claim that there was sufficient evidence for a jury to find that the union authorized sabotage, the opinion wrote:

[T]he evidence is mutually reinforcing, each piece strengthening the inferences to be drawn from the other. Though no one piece of evidence is sufficient by itself, we must view the evidence in the aggregate … This evidence includes the Unions’ prior statements, the coordinated timing of the acts of sabotage, and subsequent actions that could be interpreted as obfuscation by the Unions. It is undisputed that, the night before multiple union-organized strikes were scheduled to begin, acts of sabotage simultaneously occurred at three Care One facilities. A jury could conclude that was not just a serendipitous coincidence. We realize, of course, that this may have been the result of coordination among various union members acting independently of the Unions. However, there is also evidence that, in advance of that sabotage, the Unions engaged in inflammatory rhetoric and encouraged labor organizers to ‘become angry about their working conditions’ … [and] to take on ‘greater and more militant levels of activity’ … [which] could certainly be interpreted as a call to engage in illegal acts rather than rely only upon the collective bargaining process.

Arguably, the referenced “inflammatory rhetoric” is communication that would be normal under any union organizing campaign, and which one would never expect to encourage or lead to acts of vandalism or sabotage. By concluding otherwise, the Third Circuit sets a dangerous precedent that suggests that promoting protected concerted activity could, when combined with the unauthorized individual criminal acts of one union member (or even, someone completely unrelated to the union) be used to charge the union itself under RICO.

As for fear of economic loss, the Third Circuit noted that although “Care One did not have a right to pursue its business interests free of” fears of negative advertising campaigns by the Unions, “the Unions had a right to pursue favorable terms in a collective bargaining agreement by employing such tactics . . . only if there is a nexus between this objective and the means used.” Care One filed applications with the Massachusetts Department of Public Health, the Unions filed petitions for public hearings which delayed approval of the application. The Third Circuit held that, with regard to these regulatory activities, there was ambiguity around whether such a nexus existed, ambiguity that should be left to a jury:

There is, of course, nothing wrong with the Unions exercising their right to report violations of the law through either regulatory or criminal processes. But if the Unions implicitly intended to use these channels as a means to pursue their objective, then liability would turn on whether there is a nexus between using these processes and pursuing favorable terms in a CBA. The record, however, is not conclusive on that issue. Therefore, this is a question of fact that a jury should decide, and summary judgment in favor of the Unions was inappropriate.

Similar to the court’s holding on sabotage, the court’s finding on fear of economic loss also could have a dangerous chilling effect. The idea that engagement with a regulatory process—filing petitions for public hearings through an official government process—could amount to extortion is, on its face, extremely dangerous, not just for unions but for democracy at large. That is not even to mention the lack of clarity in the Court’s nexus test: what counts as a “nexus between using these processes and pursuing favorable terms in a CBA”? The court offers little in the form of guidance, let alone reassurance about the limits of this doctrine.

With regards to mail and wire fraud, Care One argued that the union made false and misleading statements which effectively amounted to fraud, claims which the district court and Third Circuit summarily dismissed. SEIU affiliates had engaged in a fairly typical “corporate campaign” where they protested Care One nursing homes’ policies and practices, including through billboards and other advertisements with messages criticizing Care One. For example, one flyer asked “Who’s in charge at Care One Nursing Homes?” and implied that quality of care at the nursing homes might be compromised as a result of high turnover rates. Another flyer asks, “Is Healthbridge giving your loved one antipsychotic drugs?” and mentions both the risks of such drugs and statistics about how often they were prescribed to patients at a Care One nursing home.

As the Third Circuit noted, “the Unions’ affidavits provide sufficient evidence that the affiants believed that all the material in the advertisements was truthful and accurate,” and Care One was unable to substantiate anything to the contrary. Moreover, “the law does not require the Unions to present a balanced view in their . . . advertisements.” Even if, as Care One Alleged, the union wasn’t telling the “full story,” the First Amendment protects unions’ rights to tell whichever part of the story they want—and “[i]t is unrealistic to expect that either side of a labor dispute will present a balanced view” of the dispute.

(Full disclosure: the author of Today’s News & Commentary has worked on the Care One case as a summer associate at Bredhoff & Kaiser, PLLC, one of the firms litigating the case on behalf of the Unions).

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 26

Starbucks and Workers United resume bargaining talks; Amazon is ordered to disclose records; Alabamians support UAW’s unionization efforts.

April 25

FTC bans noncompete agreements; DOL increases overtime pay eligibility; and Labor Caucus urges JetBlue remain neutral to unionization efforts.

April 24

Workers in Montreal organize the first Amazon warehouse union in Canada and Fordham Graduate Student Workers reach a tentative agreement with the university.

April 23

Supreme Court hears cases about 10(j) injunctions and forced arbitration; workers increasingly strike before earning first union contract

April 22

DOL and EEOC beat the buzzer; Striking journalists get big NLRB news

April 21

Historic unionization at Volkswagen's Chattanooga plant; DOL cracks down on child labor; NY passes tax credit for journalists' salaries.