Hugh O'Neil is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

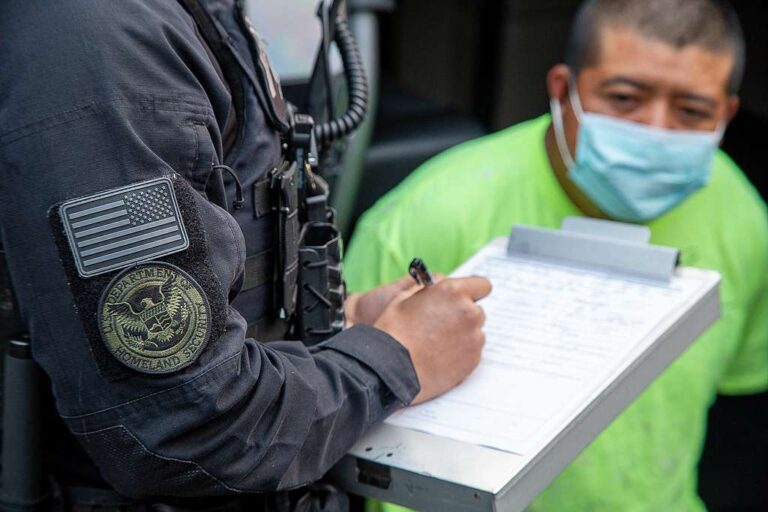

In the past year, Immigration and Customs Enforcement (ICE) agents have mounted a callous and unprecedented immigration crackdown. ICE’s tactics have violated the constitutional rights of undocumented and documented immigrants, as well as U.S. citizens. While ICE has deployed a range of enforcement strategies, raids on private businesses like hospitals, car washes, and agricultural facilities have become a mainstay. ICE’s actions have raised important questions sounding in morality, constitutionality, and politics.

What may not be top of mind to most observers is how recent events have affected workers’ rights under Section 7 of the NLRA. In this post, I argue that Trump’s immigration policy has revealed the extent of employer control over immigration-related issues, bolstering arguments that employees have a protected right to strike over federal immigration enforcement policy.

“Mutual Aid and Protection” Doctrine

Section 7 of the NLRA guarantees to workers the right to join a labor organization and bargain collectively. It also grants workers the power “to engage in other concerted activities for the purpose of collective bargaining or other mutual aid or protection.” Section 7 doctrine is expansive. Among other applications, courts have read §7 to grant employees the power to take certain collective political actions related to their status as employees.

In Eastex, Inc. v. NLRB, the Supreme Court held that employee §7 rights to engage in political activity depends, in part, on the extent to which the employer controls the issue that is the target of the employees’ activity. In particular, footnote 18 of Eastex explained that when the employer controls the target of employee concerted action, the employees’ use of economic weapons, like the strike, is likely protected. Thus, to take a classic example, because an employer has control over the temperature in the workplace, a work stoppage in opposition to a broken heating system is protected by § 7 (Washington Aluminum). On the other hand, Eastex also clarifies that where the employer lacks control, employee use of economic weaponry may be unprotected.

So, what if workers strike in pursuit of immigration policy goals? In interpreting Eastex footnote 18, two different NLRB General Counsels have arrived at opposite answers to this question. Both considered whether “A Day Without Immigrants” work stoppages were protected Section 7 activity. The advice memoranda diverged with respect to whether employers had sufficient control over the immigration policy targeted by employees to justify the walkout. The 2006 Board rejected the argument that the walkouts were protected, while the 2017 Board advised the opposite.

In the 2017 EZ Industrial Solutions memo, the General Counsel reasoned that although employers do not have direct control over immigration enforcement policy, there are sufficient actions they can take that evince enough control to justify a strike. For example, the GC posited, employers could pledge not to call or cooperate with ICE, requiring warrants and subpoenas for any searches or information requests. They could actively serve as “conduits” between their workers and “immigrant or legal aid groups.” Further, employers could publicly denounce ICE and self-designate as a “sanctuary” employer. Finally, employers can lobby legislators to change legislation or regulation.

How Current Events Effect the Doctrine

Given Trump’s focus on immigration enforcement and executive power, it is unlikely a Trump Board would reach the same outcome if EZ Industrial came up again. But in light of the breadth and depth of Trump’s immigration tactics, it is worth considering what recent events may have done to Section 7 doctrine as it relates to the use of the strike in pursuit of immigration enforcement policy.

On one view, the nearly unconstrained power of Trump’s immigration policy has weakened the argument that immigration advocacy and lobbying can fall within Section 7’s “mutual aid and protection” clause. The logic is as follows:

The Trump Administration’s immigration enforcement has included dozens, if not hundreds, of ICE raids. Even local law enforcement has been helpless in the face of this federal power; private employers are even more powerless. Even when raids have raised legal questions, workers and employers have unable to raise such challenges before it is too late. Any semblance of employer control over immigration policy is a mirage.

But this view takes a mile-high perspective and fails to reckon with how employers have responded to immigration crackdowns on the ground. Thus, instead of framing employers as completely powerless to the executive branch’s whims, a second view of the current situation highlights the various practical mechanisms employers have used to control the ways ICE interacts with the their workplaces. Indeed, this view more accurately accounts for what has happened over the last ten months.

It will always be true that an employer cannot unilaterally change federal immigration policy. But that is not what Eastex footnote 18 asks. Eastex asks not whether the employer has complete or unilateral control over the target of the employee political activity, but instead whether the employer “lack[s] . . . control.” The past year has shown that employers do not, in fact, lack control.

In the face of Trump’s ICE explosion, employers have devised protocols and procedures for how they and their employees should interact with ICE. The employee policies explain important guidelines like the warrant requirement and the the distinction between public areas of the workplace (where ICE may enter) and private areas (where ICE may not). At times, employers have refused comply with ICE except upon the issuance of a warrant or subpoena. For example, in a recent public showdown, the Los Angeles Dodgers blocked ICE’s entry to the Dodger Stadium parking lot. And when these policies failed to curb the potency of ICE raids, employers have vocalized dissent to the Trump administration. During the summer, ICE targeted factories and farms. Employers publicly denounced these efforts because the deportation of workers hurt their bottom line. They pleaded with Trump to stop. And as a result, Trump at least temporarily pulled back its focus on these sectors.

Recent events have also uncovered the extent to which employers are willing to cooperate with federal immigration enforcement. Home Depot and Lowe’s provide ICE access to security cameras. Many large corporations also maintain contracts with ICE. Although a different flavor, cooperation with ICE is still indicative of employer influence over immigration enforcement.

Conclusion

It remains to be seen which view of the last ten months will prevail. Of course, the odds are not in favor of an immigration advocate that files an EZ Industrial-type case during the next four years. Indeed, protests like “A Day Without Immigrants” are unlikely to be prevalent during the Trump administration because of the risks posed to the people that participate in them. Regardless, while the Trump administration’s actions have made many Americans feel powerless, employers can choose to take (or not take) a wide range of actions that impact the actual enforcement of immigration policy. The fact that those tools are available to employers means that the strike may also remain available to employees.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 24

In today’s news and commentary, the NLRB uses the Obama-era Browning-Ferris standard, a fired National Park ranger sues the Department of Interior and the National Park Service, the NLRB closes out Amazon’s labor dispute on Staten Island, and OIRA signals changes to the Biden-era independent contractor rule. The NLRB ruled that Browning-Ferris Industries jointly employed […]

February 23

In today’s news and commentary, the Trump administration proposes a rule limiting employment authorization for asylum seekers and Matt Bruenig introduces a new LLM tool analyzing employer rules under Stericycle. Law360 reports that the Trump administration proposed a rule on Friday that would change the employment authorization process for asylum seekers. Under the proposed rule, […]

February 22

A petition for certiorari in Bivens v. Zep, New York nurses end their historic six-week-strike, and Professor Block argues for just cause protections in New York City.

February 20

An analysis of the Board's decisions since regaining a quorum; 5th Circuit dissent criticizes Wright Line, Thryv.

February 19

Union membership increases slightly; Washington farmworker bill fails to make it out of committee; and unions in Argentina are on strike protesting President Milei’s labor reform bill.

February 18

A ruling against forced labor in CO prisons; business coalition lacks standing to challenge captive audience ban; labor unions to participate in rent strike in MN