Oscar Heanue is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

Discrimination on the basis of speech patterns — also called “linguistic profiling” — is an unfortunate reality in many workplaces. For employees who experience discrimination on the basis of an accent or dialect, it can be important to know what protections the law offers.

What is Linguistic Profiling?

Linguistic profiling occurs when a listener makes judgments about a speaker’s social characteristics (such as race or social class) based on their accent, dialect, or other speech patterns. This form of profiling can lead to discrimination based on the listener’s implicit or explicit biases.

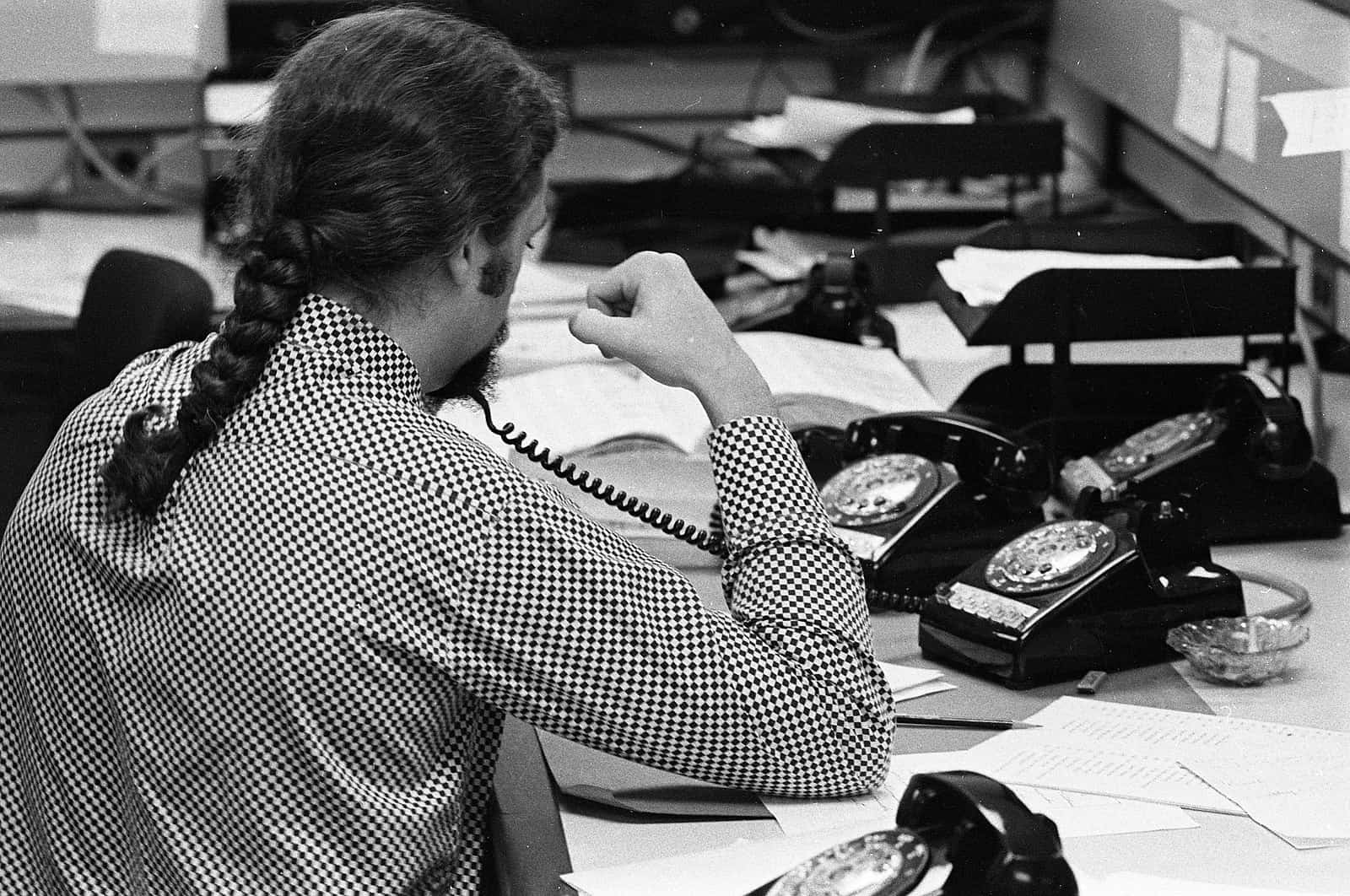

The term was first coined by Dr. John Baugh, whose pioneering research on linguistic profiling found that prospective tenants who belong to racial and ethnic minority groups may be subject to discrimination in the housing market even if they never actually meet a landlord. In a study conducted in the San Francisco Bay Area, Baugh found that prospective tenants who placed calls requesting to see an available apartment were significantly less likely to receive a call-back if they spoke in an African American or Chicano dialect. Subsequent research has indicated that linguistic profiling may lead to discrimination against Black and Hispanic callers seeking other publicly available goods or services. A 2019 study, for example, found that callers who were identifiable as Black based on accent cues were more likely to be told that pediatricians’ offices were not accepting new patients.

These issues may be especially salient for non-native speakers of a language. Linguistic profiling occurs quickly, and may result in snap judgments about a person’s background or abilities. Professionals with an identifiably foreign accent often have their competence questioned at a higher rate than their peers.

While linguistic discrimination against racial minorities and non-native speakers of a language has been well-studied, research shows that linguistic profiling also occurs among individuals with the same racial or ethnic backgrounds and native language. Regional accents, for example, may be viewed as markers of character or status: in a 2012 study, researchers at the University of Chicago found that children as young as five viewed those with Northern accents as more likely to be “in charge,” while those with Southern accents were seen as “nicer.”

Biases against particular regional accents or dialects may persist even within their region of origin. Residents of Eastern Kentucky, for example, have been found to hold negative stereotypes about the “socio-intellectual status” of Appalachian English speakers when compared to speakers of other dialects. These stereotypes can have real impacts. Individuals who have a regional accent which is perceived as low-status may feel a desire to “lose” their accent in order to avoid such negative stereotyping.

Linguistic Profiling in the Workplace

Linguistic profiling can be a major source of invidious discrimination in the workplace. Hiring decisions, promotions, and other key work-related matters may be influenced by linguistic profiling, which are often cabined within notions of “professionalism” that may be steeped in white supremacy and classism. Scholars have noted that workplace professional standards often disfavor the dialects of Black and other minority employees, creating an environment where minority employees feel pressure to code switch when speaking with colleagues.

A large body of research suggests that linguistic profiling may impact hiring decisions. Accents and dialects — both foreign and regional — can impact a candidate’s job opportunities. A 2016 study found that managerial respondents “actively discriminated” against candidates who spoke Chinese-, Mexican-, or Indian-accented English. Candidates received even lower marks for customer-facing roles. Certain regional accents and dialects have also been shown to impact hiring rates in the US; candidates with Appalachian dialects, for example, may face bias in both hiring and performance appraisals.

Even when linguistic discrimination does not cause an employee to be passed over for a job, it can impact the employee’s treatment and compensation while working at the job. In the US, research indicates that having a “non-mainstream” accent or dialect results in lower pay. This bias against “non-mainstream” accents appears to transcend borders and languages, as a recent study from the Universities of Chicago and Munich found a 21 percent wage gap between workers in Germany with regional accents and those with “mainstream” accents.

Linguistic racism against minority employees in the US is especially pronounced and can further compound racial inequities. According to University of Chicago researchers, Black employees whose voices study participants “could distinctly identify as Black” earn, on average, 12 percent less than their counterparts whose racial identity was not identifiable.

Low pay does not tell the whole story, though. Employees with “non-mainstream” accents or dialects may be treated differently by their colleagues. Non-native speakers of a language, for example, frequently report feeling judged, devalued, or excluded while at work, and may also experience more limited career opportunities and mobility. And even when an employee’s coworkers are not an issue, employees in customer-facing roles can face harassment on the basis of their accent or dialect.

Fortunately, in many cases, the law provides remedies for employees who suffer linguistic discrimination.

The Law on Linguistic Profiling by Employers

Statutory employment law in the United States makes no direct reference to discrimination based on accent or dialect, but it does offer limited protections. Title VII’s ban on discrimination based on national origin has been held to encompass discrimination on the basis of foreign accents, and successful cases have been brought under the law. In 2012, for example, the EEOC secured a $975,000 settlement with Delano Regional Medical Center in California based on harassment and mockery of Filipino employees. There are limits to the law’s reach, however. Where an employee’s accent “interferes materially with job performance,” the EEOC cautions that the law may not offer protection.

The applicability of Title VII is less clear in cases where an individual experiences linguistic discrimination not tied to national origin. When accent or dialect is used as a proxy for race, Title VII’s bar on race and color discrimination may be implicated. For example, in a Title VII race discrimination case, Mayse v. Protective Agency, Inc., the court considered that the employer had written “sound good — black?” on the plaintiff’s job application after an initial phone conversation.

The law offers little protection, however, in cases where linguistic profiling occurs but does not implicate the statutory prohibition on race or national origin discrimination. On the international stage, however, there is growing precedent for that to change. France recently passed a law barring discrimination on the basis of regional accents. The law, passed by an overwhelming 98-3 margin, takes a hard stance on accent discrimination, making it a criminal offense to discriminate on the basis of accent in areas including employment, housing, education, and access to goods or services.

France’s law is notable as the first to explicitly bar discrimination against all accents and dialects, including native accents. The move could set the stage for other countries to follow suit. While it remains to be seen how effective the law will be in curbing accent discrimination in France, it may be an area for U.S. lawmakers to monitor. Though linguistic profiling may not be the first form of discrimination that many think of, it can have serious and adverse consequences for the careers of individuals with non-mainstream accents or dialects.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]

June 27

Labor's role in Zohran Mamdani's victory; DHS funding amendment aims to expand guest worker programs; COSELL submission deadline rapidly approaching

June 26

A district judge issues a preliminary injunction blocking agencies from implementing Trump’s executive order eliminating collective bargaining for federal workers; workers organize for the reinstatement of two doctors who were put on administrative leave after union activity; and Lamont vetoes unemployment benefits for striking workers.

June 25

Some circuits show less deference to NLRB; 3d Cir. affirms return to broader concerted activity definition; changes to federal workforce excluded from One Big Beautiful Bill.

June 24

In today’s news and commentary, the DOL proposes new wage and hour rules, Ford warns of EV battery manufacturing trouble, and California reaches an agreement to delay an in-person work mandate for state employees. The Trump Administration’s Department of Labor has advanced a series of proposals to update federal wage and hour rules. First, the […]