Dr. David Doorey is an Associate Professor of Labor and Employment Law at York University in Toronto.

In a recent OnLabor post, Michael Migiel-Schwartz examined the growing movement to abolish at-will employment, the distinctly U.S. employment law doctrine that permits employers to terminate employees for no reason at all with no prior notice. Several months ago, Professors Kate Andrias and Alexander Hertel-Fernandez published a detailed report for the Roosevelt Institute arguing for at-will to be replaced by a statutory “just cause” model that would require employers to demonstrate that they had a valid business reason to terminate an employee. Professor Rachel Arnow-Richman has long argued for the replacement of at-will employment with a model that requires notice of termination.

In the push to reform and replace at-will employment, the Canadian system of employment law is often identified as an example of a preferable model. In reality, there are a variety of Canadian models that function in a somewhat complicated and overlapping system of common law and statutory regulation of employment contracts. For the purposes of the U.S. debates, it might be useful to provide a quick description of the Canadian approach to the termination of non-union employment contracts.

Although the U.S. and Canada share a similar background in the received common law of Britain, by the late 19th century the legal models of the two countries had diverged sharply in their treatment of termination of employment contracts. By the 1880s, the presumption of at-will employment was firmly rooted in the U.S. In 1908, consistent with the prevailing British approach, an Alberta court ruled that an employment contract is terminable only with “reasonable notice.” Subsequent Canadian decisions adopted this approach and then, in an important 1936 decision called Carter v. Bell, the Ontario Court of Appeal confirmed that in Canada, “there is implied in the contract of hiring an obligation to give reasonable notice of an intention to terminate” the contract.

Therefore, by the early twentieth century, the common law in both countries permitted employment contracts to be terminated for any or no reason at all, but in Canada there was a legal presumption that notice of termination was required. Common law courts in Canada rarely ordered employers to reinstate terminated employees; failure to provide notice was a breach of contract—a “wrongful dismissal”—that gave rise to damages calculated based on the loss of wages and benefits that the employee would have received had proper notice been provided.

This remains the presumptive common law model today in Canada. Courts determine how much notice is “reasonable” by applying criteria that act as a proxy for how long it might take the employee to find comparable alternative employment. Those criteria, known colloquially as “the Bardal Factors” after the decision that first listed them, include length of service, character of employment, age of the employee, and availability of similar employment having regard to experience, training, and qualifications of the servant. Notice periods can range from as little as a two weeks for a short-term employee up to two years or more for very long service employees, as I explain in this chapter from my text The Law of Work.

The purpose of requiring employers to provide notice of termination is to give the employee time to prepare for the loss of employment and to search for a new job. However, there are a number of exceptions to the general rule that employers must provide reasonable notice of termination. For example, an employer is not required to provide notice when the employee has committed a serious (or repudiatory) breach of the contract (“summary dismissal”), such as theft, violence, or gross incompetence.

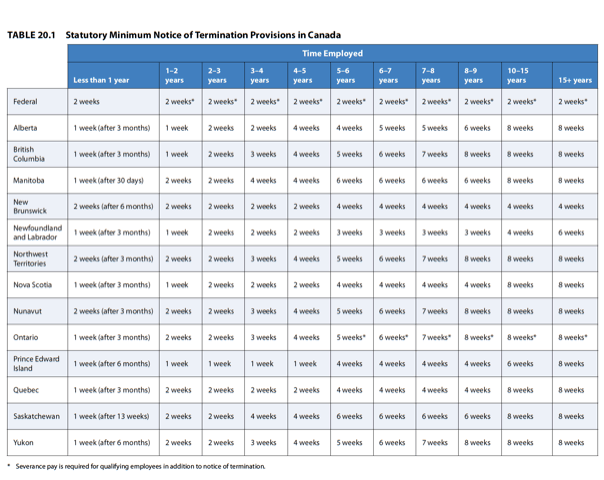

In addition, because the requirement to provide reasonable notice of termination is an implied contract term, it can be overridden by expressed agreement of the parties. In theory this means that employers could include a term permitting termination at-will and thereby avoid the implied obligation to provide notice. However, that option was removed in relation to most (but not) all employees beginning in the 1960s when Canadian governments introduced statutory minimum periods of notice of termination (see chart). As a result, employees who are covered by the labor standards legislation are entitled to receive at least the minimum amount of notice required by the legislation. Therefore, an employment contract term can limit notice to the statutory minimum, but it is unlawful to contract out of the statutory notice period.

In addition to the statutory and common law requirement for notice of termination, many Canadian employees are covered by “just cause” protection in some form. For starters, virtually every unionized employee in Canada is covered by just cause protection found in the collective agreement. Approximately 31 percent of Canadians are unionized. Unions enforce the just cause provisions before labor arbitrators and an immense volume of arbitral just cause case law exists spanning over 70 years.

Only three Canadian jurisdictions have introduced statutory just cause protection applicable to non-union employees: the federal jurisdiction (introduced in 1978), Quebec (1979), and Nova Scotia (section 71) (1975). These laws were inspired by ILO Recommendation 119 on Termination of Employment (1963) which recommended that states protect employees from termination of employment unless there exists “a valid reason…connected to capacity or conduct of the worker” or the operational requirements of the establishment.

In Canada, provinces have primary jurisdiction over employment regulation with the result that the federal “unjust dismissal” provisions reach only about 8 percent of Canadian workers who fall within federal jurisdiction. Those provisions apply to any non-union employee who is terminated after at least 10 years of consecutive employment. The Supreme Court of Canada has ruled that the unjust dismissal provisions were intended to mimic just cause provisions found in collective agreements. Under the statutory unfair dismissal laws, tribunals are granted powers to reinstate employees terminated without just cause. Considering just cause provisions in collective agreements and the statutory unfair dismissal provisions in three Canadian jurisdictions it is a reasonable guess that approximately 35-40 percent of Canadians have some form of just cause protection.

A striking feature of the presence of these greater protections for workers in Canada is how little employers complain about them. Not even the most conservative of Canadian politicians argue in favor of at-will employment. In recent consultations during an Ontario government review of employment laws, the powerful lobby groups Retail Council of Canada and Restaurants Canada, which together boast membership including Walmart, Apple, McDonalds, Yum Brands, Staples, Best Buy, among other large American companies, did not raise any concerns about notice of termination requirements. A review of federal labor standards legislation attracted not a single employer submission demanding repeal of either notice requirements or the just cause standard.

Nor is there evidence to suggest that the termination rules discourage investment in Canada. Wal-Mart just announced a $3.5 billion investment to raise its Canadian profile. Starbucks has over 1400 Canadian stores. Tech companies, including Amazon, are aggressively expanding their Canadian footprint. When U.S. companies cross the border into Canada, they accept the rules governing termination of contracts as a normal cost of doing business. Only at home in the U.S. do these companies and their lobbyists defend at-will employment as if it is sacred ground.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 14

More circuits weigh in on two-step certification; Uber challengers Seattle deactivation ordinance.

July 13

APWU and USPS ratify a new contract, ICE barred from racial profiling in Los Angeles, and the fight continues over the dismantling of NIOSH

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

the Supreme Court allows Trump to proceed with mass firings; Secretary of Agriculture suggests Medicaid recipients replace deported migrant farmworkers; DHS ends TPS for Nicaragua and Honduras

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]