Eric Jang is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

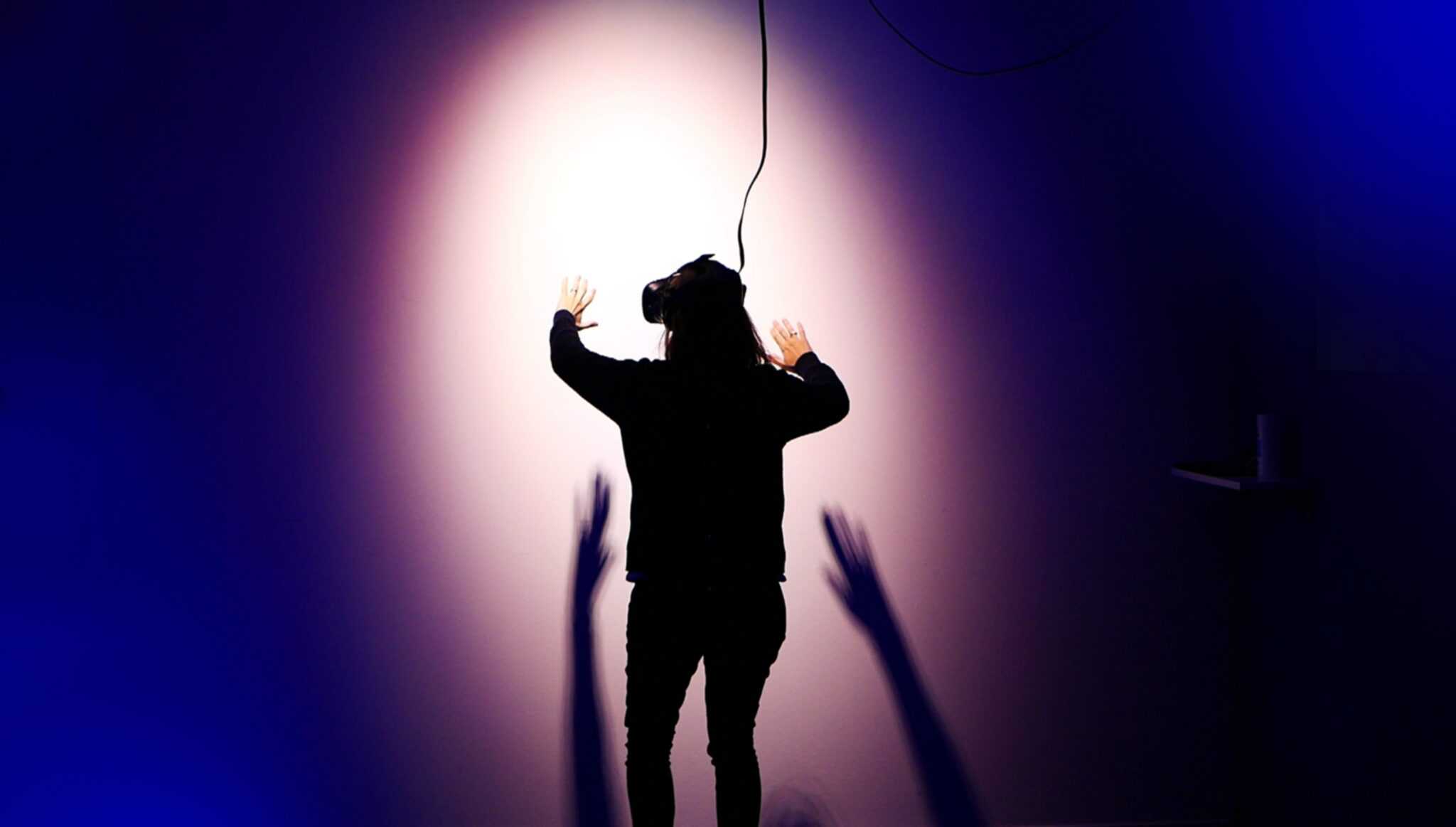

Remote work is here to stay. Although the COVID-19 pandemic that necessitated the Work-From-Home (WFH) revolution is on its way out (fingers crossed), 83% of employees and 63% of employers have expressed a desire for a hybrid model for the future: working both at the office and remotely from home depending on individual needs. The WFH revolution has galvanized big tech companies to find new ways to ease the challenges of working remotely, and a new development has captured their imagination. Enter the metaverse: a space created in virtual reality (VR) so that even when you are working from home, you can feel like you are at the office with your colleagues.

Integrating VR into the workspace is not a new phenomenon birthed by the pandemic. Many large businesses ranging from Walmart to Accenture have utilized VR to train and recruit employees, even before the pandemic. However, the metaverse distinguishes itself by providing a VR space for collaboration, rather than instruction. With the new potential for the metaverse, VR’s usage in business is projected to grow and impact up 23.5 million jobs by the year 2030. Although the market’s enthusiasm signals an exciting future on the horizon, the metaverse also presents a threat to employee privacy. If regulations fail to keep up with the rapid advancements in VR technology, it could allow employers to surveil even the thoughts and feelings of their staff.

Working in a Virtual Office

At its essence, working in VR is much like a Zoom call where employees can hold conferences, but instead of opening your laptop to join a meeting, you put on a VR headset. Meta’s flagship VR headset is the Oculus Quest 2, which comes with two hand-held controllers to capture your hand’s movements. The headset lets you experience what your avatar would see and hear in the metaverse, thereby providing you with a first-person, visual and auditory experience of a simulated VR office.

To join a meeting in Meta’s Horizon Workroom, you first have to design your avatar, customizing every aspect of its appearance such as its apparel, skin color, and hair style. The avatar is a representation of you in this virtual space and will be what other Workroom participants see as you interact with one another. It will mimic your hand gestures based on the movement of your Oculus controllers, and nod or shake its head along with your own head movements. In Microsoft’s Mesh, you can even move your avatar around the VR office, and the VR headset’s output will adjust to your change in location.

The VR workspace is also customizable. Depending on your needs, you could host a meeting in a round-table conference room or arrange the desks into an intimate lecture hall. You could even bring your own laptop into the VR environment by scanning your desk and keyboard with the Oculus controllers. With your computer’s display projected in front of you in VR, you can effectively perform work in the metaverse. The myriad of features offered by Meta’s Horizon Workroom attempts to close the gap between working in person at an office versus working remotely from your home. But the advanced technologies employed to transform remote work could also have troubling implications for employees’ data privacy.

Privacy in the Metaverse

Working in the metaverse could significantly erode the boundary of privacy between employers and employees. To track and project our physical motions, VR headsets need to collect our biometric data. In fact, using a VR headset for 20 minutes can generate up to 20 million data points about your body. Current VR functionalities that track a person’s head and hand movements can be used to identify the user with up to 95% accuracy. As a result, VR tracking data can serve as a digital fingerprint that makes it impossible to maintain your anonymity.

As VR technology improves, it is poised to collect even more information from our bodies. Meta has promised that its next iteration of the Oculus headset will also have eye- and face-tracking features so that your avatar can roll its eyes or smile in concert with your real self. On its surface, data about where you are looking and your facial expression may appear benign, but they can have disturbing implications for workplace monitoring. For example, your facial expressions to different workplace stimuli could be studied and used to draw inferences about your emotional state. Based on these inferences, an employer could find patterns in your emotions and discover who you enjoy working with and which tasks you find fulfilling, or the opposite. Data about your eye movements could be used by Meta and other companies facilitating VR workspaces to deliver highly customized ads, or be used to determine your level of engagement at work. Even worse, eye-tracking technologies can be used to make predictions about your mental illnesses or who you are attracted to, and even your sexuality. Therefore, working in the metaverse could open a trove of intimately personal data that for employers to monitor and appraise workplace performance of their employees.

Lagging Regulations

Unfortunately, it is unclear how much of the data collected by VR companies will be protected under existing laws. For example, the Biometric Information Privacy Act (BIPA) of Illinois defines biometric information to include scans of your retina, hands or “face geometry”, but it does not address whether tracked movements fall within its definition. Furthermore, the BIPA requires employers to provide ample notice and consent before collecting biometric data, but employees will be hard-pressed to decline if it is conditioned upon their employment or if their denial could reflect poorly on them. Finally, the BIPA restrictions on what employers can do with employees’ biometric data does not prevent employers from monitoring and analyzing the employees’ behavior and emotional states.

In other states, biometric data privacy laws closely mirror the BIPA and share the same shortcomings. Texas’s Capture or Use of Biometric Information Act and Washington’s Biometric Identifiers Law similarly require notice and consent from employees when it comes to collection and usage of biometric data. However, both statutes are overly broad in defining what employers can do with their employees’ biometric data — so long as they have their employees’ consent, employers can sell, lease, and otherwise disclose biometric data for any “commercial purpose.” This could allow employers to hire third-party consultants to track and analyze your biometric data for workplace monitoring. All three statutes allow employers to retain the biometric data for at least as long as the employee is with the company. As a result, the current legal framework surrounding biometric data leaves a gap wide open for employers to collect, monitor and exploit their employees’ personal data through the metaverse.

The metaverse could fundamentally reshape how we think of physical office spaces and secure a right for people to choose where they work. But if left unchecked, it could allow employers to open a window into some of the most private details of their employees’ minds. As big tech companies continue to push forward towards innovation, lawmakers must provide sensible regulations to ensure that the future of work maintains the essential boundaries between employers and employees.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

In Today’s News and Commentary, the Supreme Court green-lights mass firings of federal workers, the Agricultural Secretary suggests Medicaid recipients can replace deported farm workers, and DHS ends Temporary Protected Status for Hondurans and Nicaraguans. In an 8-1 emergency docket decision released yesterday afternoon, the Supreme Court lifted an injunction by U.S. District Judge Susan […]

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.