Sharon Block is a Professor of Practice and the Executive Director of the Center for Labor and a Just Economy at Harvard Law School.

Reed Shaw is a Policy Counsel at Governing for Impact.

For the first time in decades, public attention was focused on union organizing in the American South. Eyes were on two German car companies, both the subject of high intensity organizing campaigns courtesy of the resurgent United Auto Workers (UAW) – one in Tennessee and one in Alabama. These two high profile campaigns – similar in so many respects – yielded very different results. In Tennessee, workers at the Volkswagen plant overwhelmingly voted for the union but, just one month later, the union lost an election at Mercedes in Alabama.

What can explain the difference? We believe that the difference is due to the very different response by the two companies to the union’s campaigns. At Volkswagen, the company remained neutral. But at Mercedes, the company launched an aggressive campaign to undermine support for the union. These efforts included forcing workers to sit through videos and lectures on a daily basis about the supposed dangers of organizing, as well as incessant text and direct mail messages. There are also allegations that Mercedes’ tactics veered into the unlawful – firing workers because they supported the union and making threats.

Mercedes – a company whose German employees are unionized – didn’t dream up this campaign of coercion on its own. It joined a growing list of employers who hire outside consultants and law firms to bust union organizing efforts. These union-busters are hired to run sophisticated campaigns to dissuade workers from exercising their rights to form and join a union. Employers like Mercedes pay union-busters exorbitant amounts of money to design aggressive – sometimes unlawful – tactics to secure a win against a union.

But few workers are aware of the great lengths (and expense) to which their employers’ go to deprive them of a union. If they did know, perhaps they would treat union-busters’ – who often present themselves to workers as neutral educators – claims with a bit more skepticism.

Congress wanted workers to know when they were being manipulated by professional union-busters. That’s one reason it passed the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA) long ago in 1959. The statute requires a series of disclosures from unions, employers, and union-avoidance consultants and law firms to ensure transparency about spending on union campaigns, so that workers and the public would know about the relationships that existed between the union-busters and employers.

But workers and the public remain in the dark as a result of widespread noncompliance with this obscure but important law. In 2016, the Department of Labor (DOL) estimated that roughly three-quarters of anti-union persuader activity went unreported between 2009 and 2014. In Alabama, neither the union-busting firms nor Mercedes disclosed the terms and conditions of their anti-union activity prior to the election.

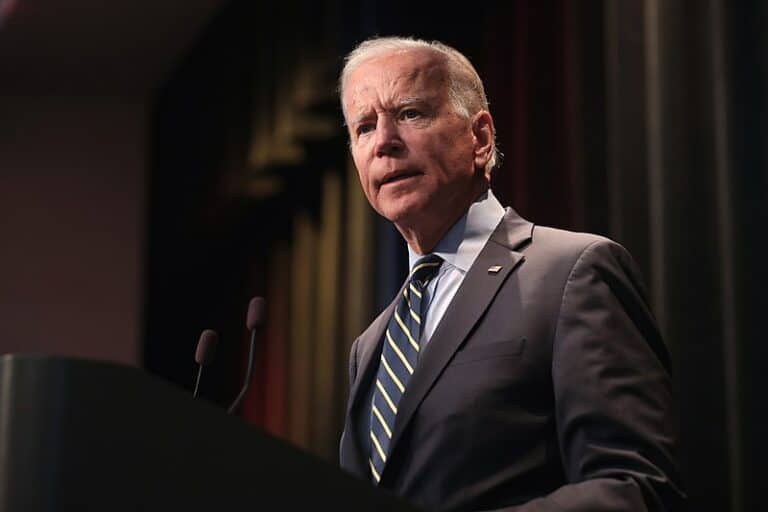

The divergent results at Volkswagen and Mercedes underscore how important it is for the law to be enforced. We just released a report encouraging the Biden Administration, which has done so much to support workers’ right to unionize, to do even more. First, DOL should fully enforce a regulation already on the books and rescind what was supposed to be a temporary reprieve put in place during the Obama Administration. We also recommend that DOL require employers who use these union busting consultants to reveal whether they receive certain kinds of federal funding, like grants, loans, and loan guarantees. Taxpayers deserve to know when their taxes are inadvertently funding union-busting efforts.

Other agencies could have a role to play as well. For example, the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) – chaired by the unabashedly pro-worker Lina Khan – should consider investigating the union-busting industry for anti-competitive behavior if consultants’ relationships with employers make it more likely that those employers coordinate on wages and strategy. The theory would that in sectors where a small number of anti-union consultants serve clients that comprise a large share of a particular sector, the FTC could consider investigation acts or practices that “facilitate” coordination in a way that makes it easier for parties to coordinate wages or other behavior in an anticompetitive manner. The legal question is whether these types of arrangements constitute “hub and spoke” conspiracies where an entity that has vertical relationships with several competitors helps coordinate anticompetitive behavior between the competitors.

It’s not all doom and gloom. As we’ve seen in a recent wave of successful organizing campaigns, even sophisticated anti-union efforts are no match for worker solidarity and effective worker organizing. The historic Volkswagen win, the UAW’s continued efforts to organize Southern workers, and near-record levels of public support for unions demonstrate the movement’s vibrancy.

But make no mistake: for countless reasons, the deck is stacked against workers who attempt to organize. Our hope is that the recommendations in our report help regulators pursue a course of action that helps tilt the playing field a smidge back toward level.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 5

Minnesota schools and teachers sue to limit ICE presence near schools; labor leaders call on Newsom to protect workers from AI; UAW and Volkswagen reach a tentative agreement.

February 4

Lawsuit challenges Trump Gold Card; insurance coverage of fertility services; moratorium on layoffs for federal workers extended

February 3

In today’s news and commentary, Bloomberg reports on a drop in unionization, Starbucks challenges an NLRB ruling, and a federal judge blocks DHS termination of protections for Haitian migrants. Volatile economic conditions and a shifting political climate drove new union membership sharply lower in 2025, according to a Bloomberg Law report analyzing trends in labor […]

February 2

Amazon announces layoffs; Trump picks BLS commissioner; DOL authorizes supplemental H-2B visas.

February 1

The moratorium blocking the Trump Administration from implementing Reductions in Force (RIFs) against federal workers expires, and workers throughout the country protest to defund ICE.

January 30

Multiple unions endorse a national general strike, and tech companies spend millions on ad campaigns for data centers.