Gwen Byrne is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

Apprenticeships have garnered bipartisan support as a way to enhance economic prosperity. Democrats and Republicans alike advocate for the use of apprenticeships to cultivate a skilled and diverse workforce, offering technical proficiency and sustainable wages to the middle class. This bipartisan enthusiasm isn’t new. President Clinton pledged to ensure that his administration would guarantee workers “get training and retraining throughout their careers.” President Obama’s labor secretary described apprenticeships as “the other college – without the debt” and invested 175 million dollars in American Apprenticeship Grants. President Trump instituted Industry-Recognized Apprenticeship Programs (IRAP) with the intent to “allow employers to take a more active role in training and quickly develop new programs.”

The importance of these initiatives is especially salient as four-year degrees start to fall out of vogue. 2022 saw the smallest percentage of high school graduates enroll in college in two decades. College-age Americans cite escalating student debt, a lack of meaningful education, and an unreasonable time commitment as reasons that college is losing its shine. Yet, despite efforts to revamp alternative paths to high-paying jobs, apprentices receive a mere 2 percent of the taxpayer that college students do and severe labor shortages in the skilled trades persist. The question is, what are these plans missing?

History of Apprenticeships

The Department of Labor (DOL) defines an apprenticeship as having three pillars: a paid job, education, and credentials. Apprenticeships can be split into two buckets: state and federal. State-level apprenticeships are run by recognized state apprenticeship agencies registered with the DOL’s Office of Apprenticeships (OA). Federal apprenticeships are run by OA field offices and are overseen by DOL. In total, there are 607,509 active apprentices across the country. Over half of apprenticeships are in construction or public administration. After hitting a low in 2012, the number of Recognized Apprenticeship Program (RAP) enrollees has been steadily increasing. A mix of employer and government funding typically covers the cost of training apprentices, which can carry a stick price of up to $250,000.

A staunch history of racism and sexism has shaped the apprenticeship industry. In the 1960s and ‘70s, vocational education at the high school level was used to “segregate poor and minority students to preserve the academic curriculum for middle- and upper-class students.” Unions, which exercise significant control over trade apprenticeships, long excluded women and non-whites from their programs. While policies have changed, white men continue to dominate the market. Black apprentices consistently have the lowest earnings, in part because they are concentrated in southern states with lower minimum wages.

Apprenticeship programs also tend to favor male-dominated industries, like construction and technical trades. This preferential structure has numerous consequences. For one, there is now a labor surplus in construction. Meanwhile manufacturing, education, and health services all suffer from labor shortages. Childcare development and registered nursing apprenticeships exist, but their enrollment levels are dwarfed compared to other occupations, such as electricians and carpenters. Women constitute only 13 percent of all apprentices, dropping to a mere 3 percent in construction. Sexual harassment and checkerboarding, a hiring practice that moves minorities and women between short-term projects while reserving steady positions for white men, further deters their participation.

Lastly, the failure to get more young people interested in apprenticeships is likely a result of cultural perceptions. Managers in technical trades, like plumbing, note that people look down on manual labor, which makes recruiting an uphill battle. Emphasizing four-year degrees as the preferred and “best” option after high school disincentivizes, and at times stigmatizes, entering skilled trades. Although those beliefs are unfounded, the most “prestigious” and high-paying jobs in the United States are indeed only accessible to college graduates. Comparatively, European countries often use apprenticeships as an on-ramp to coveted professions. In Switzerland, 25 percent of students attend a traditional university and 70 percent pursue apprenticeships.

Why Apprenticeships Fall Short

Addressing racism, classism, and sexism in apprenticeships requires robust policy changes. Yet, it seems that both parties, whether intentionally or not, enact programs that maintain these troublesome histories. Republican think tanks have started to use “apprenticeships” as code for “keep students out of college” and “undermine the agenda of the woke left.” Right-wing policies also emphasize employer interests over worker-development and slash government oversight. In other words, they seek to generate a pool of cheap labor and make education antithetical to hands-on learning. Senator Tom Cotton’s apprenticeship bill, heralded as a way to heal from the “college catastrophe,” epitomized this ideal; it would tax university endowments to generate apprenticeships, exclude anyone with a bachelor’s degree from participating, and require no more than minimum wage for trainees.

Similarly, Trump (perhaps echoing his own role starring in NBC’s “The Apprentice”) developed the IRAP model, which delegated apprenticeships to third parties and reduced DOL oversight. Proponents viewed IRAPs as a way to decrease bureaucratic headaches and encourage industry leaders to take a more active role. In reality, decentralization meant less funding for union apprenticeships, lower-quality programs, and lower wages. The proposal drew ire from unions across the country. Corporations were exempted from stepwise wage increases, prevailing wage requirements, and equal-opportunity employment. These approaches compound, rather than alleviate, the problems already endemic to apprenticeships; they perpetuate earnings gaps, refuse diversity efforts, and prioritize efficiency over quality.

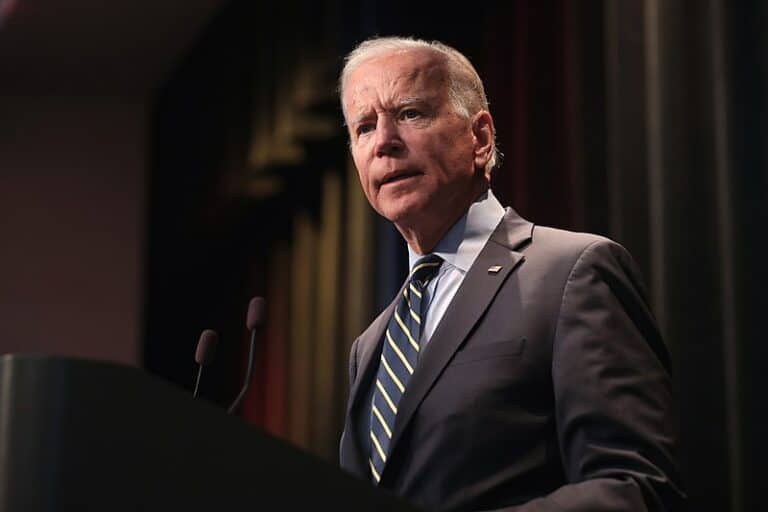

Democrats have made more substantial steps to expand and diversify apprenticeships, but fail to debunk the assumption that apprenticeships are only meant for blue-collar Americans. Biden’s Good Job Challenge attempted to remedy the issue of prevailing attitudes and awarded grants in cloud computing, wind power, and rural primary care. Expanding RAPs to high-paying sectors might diminish the comparative advantage college degree holders have in higher average earnings, but it cannot negate clear funding discrepancies. The federal government spends upwards of $70 billion on higher education; it spends $285 million on apprenticeships. The undeniable prioritization of college in funding parallels the same tension that surveyed voters voice; apprenticeships are good for someone, but that someone would never be me or my kid.

Lastly, Democratic policies have yet to resolve the racial and gender-based inequities that plague apprenticeships. Although Biden’s Apprenticeship Ambassador Initiative increases access to RAPs for women, people of color, people with disabilities, and other underrepresented communities, it falls short of its equitable aims. As of 2023, the median hourly-rate for women apprentices is only two-thirds of men’s. Persistent devaluation of women-led industries is partially to blame; apprentice-trained childcare development specialists have a median wage of $9.75 whereas electricians have a median wage of $23.46. Apprenticeship programs also often lack funding for childcare, transportation, and health insurance, leaving behind the populations they purport to serve.

Conclusion

Why should we care? Rethinking job training and breaking out of the restrictive bounds of four-year degrees allows us to reimagine what a successful career looks like. It encourages more flexible and varied ways of learning that decouple a college education from an individual’s worth. Apprenticeships are also one way that the United States can modernize its workforce and keep up with other countries in fields like manufacturing. With policy changes that focus on equity and robustly fund nontraditional fields, politicians can avoid falling into the same traps as before.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.