Sarah Leadem is a joint degree candidate at Harvard Law School and the Harvard Kennedy School of Government.

On February 11, 2022, the Southern District Court of New York preserved just cause protections for fast food workers in Restaurant Law Center v. City of New York. This decision lands a significant blow to the norm of at-will employment and is a boon to just cause advocacy in other cities and industries.

The subject of the litigation is New York City’s 2021 “Wrongful Discharge Law.” Under this law, after an employee completes a 30-day probation period, she cannot be fired or have her average hours reduced by more than 15% without just cause. An employer has just cause if (1) the employee failed to perform satisfactorily in her job duties, or (2) she committed conduct that was harmful to the employer’s legitimate business interests. The new law requires use of progressive discipline and written notice of termination, and it gives employees the right to arbitrate a wrongful dismissal. Layoffs for “bona fide economic reasons” due to “reductions in volume of production, sales or profit” are exempt.

The lawsuit was filed by the New York State Restaurant Association and the Restaurant Law Center. While the federal district court declined to consider state-based causes of action, it examined three legal issues: (1) preemption under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA); (2) constitutionality under the Dormant Commerce Clause; and (3) preemption under the Federal Arbitration Act.

NLRA Preemption

The court’s analysis focused on preemption under the NLRA, finding that the law was not preempted. The court analyzed the law under the Machinists doctrine developed by the Supreme Court. Under this doctrine, the NLRA preempts state and municipal laws that regulate conduct Congress intended to be left unregulated. But laws that provide “minimum labor standards” and do not intrude on the bargaining process are not preempted.

Plaintiffs argued that the law interferes with the collective bargaining process, by legislating on issues traditionally subjected to bargaining and essentially providing a collective bargaining agreement to workers through a municipal law. According to plaintiffs, this law is not generally applicable as a “minimum labor standard” because it applies narrowly to a particular industry and its provisions go far beyond establishing “background rules” against which employers and workers may negotiate. Finally, plaintiffs urged that the law shifts the balance of power toward employees, creating an incentive to unionize, and was advanced by union interests.

The court disagreed. According to the court, the purpose of NLRA is to regulate the processes of collective bargaining, not their substance. State and municipal laws are preempted only when they interfere with or frustrate those processes. Under the court’s conception, this law does not disrupt any balance of power that might interfere with those processes because it applies equally to union and to non-union workers across the entire fast food industry. The court characterized the law as a “minimum labor standard” of general applicability aimed at promoting job stability for hourly employees in a particular sector — the fast-food restaurant industry.” The court also defined the law as dealing with termination, not the process of collective bargaining, peeling it away from the preemptive scope of the NLRA.

Dormant Commerce Clause

The court ruled that the Wrongful Discharge Law did not violate the Dormant Commerce Clause. The “Dormant Commerce Clause” refers to a constitutional law doctrine that reads the Commerce Clause of the U.S. Constitution to implicitly prohibit state or local regulations that discriminate against or unduly burden interstate commerce.

Plaintiffs argued that the law discriminates by means of its statutory definition of a “fast food restaurant.” The underlying law (New York’s Fair Workweek Law) defines a “fast food restaurant” as a chain with 30 or more restaurants nationwide. Plaintiffs argued that this definition limits the law’s application only to interstate food chains, thereby discriminating against these operators.

The court here was brief in its response. It concluded, overall, that the Wrongful Discharge Law is a general welfare statute that bears no substantive differences in effect for interstate versus intrastate employers. To support this conclusion, the court relied heavily on a case in the Second Circuit, Vizio v. Robert Klee, which declined to find the similar requirement of a “national market share” as discriminatory against interstate actors. The court intimated that there could be — at most — an indirect burden on interstate restaurants but said this was not enough. Overall, the court held that the law affects all fast-food companies equally and is not discriminatory against out-of-state actors.

Federal Arbitration Act Preemption

Finally, the court held that the law was not preempted by the Federal Arbitration Act (FAA). The FAA prohibits regulations that limit the enforcement of private arbitration agreements. Plaintiffs argued that the FAA requires arbitration agreements to be consensual. Because the Wrongful Discharge Law mandates arbitration over alleged wrongful terminations, the law violates that consent principle. Plaintiffs argued that, as such, the law frustrates the ability of employers to comply with the FAA’s consent requirement. The court swiftly rejected this argument. Instead, it found the FAA silent on non-consensual arbitration and held that plaintiffs failed to prove preemption. Importantly, the court here did not make a finding on whether the FAA does in fact permits state and local regulations to mandate arbitration, but — at a minimum — found lack of evidence of preemption, relying heavily on the silence in the FAA.

Implications of this Decision

New York City has already begun enforcing the law. In December 2021, NYC’s Department of Consumer and Worker Protections announced it had resolved its first case under the new law by securing a settlement with a Subway franchisee that illegally terminated two employees.

NYC’s Wrongful Discharge Law fits into a patchwork of other state and local laws that have cut back on the norm at-will employment. Since 2002, California’s Displaced Janitors Opportunity Act has limited at-will termination of janitors during changes in building contractors. Los Angeles County passed a Right of Recall ordinance that provides a right to return to certain workers after a COVID-19 related layoff. Most significant, however, is Philadelphia’s 2019 just cause law that requires employers to provide a reason for termination to parking workers. However, none has gone as far nor covered as many workers as New York City’s law. It may be the “biggest win for the just-cause movement to date.”

This ruling is significant for the just cause movement. This victory is the result of and may embolden the growing movement of labor organizations calling for just cause protections. OnLabor’s initial report on NYC’s Wrongful Discharge Law highlighted similar legislation contemplated in California, Illinois, and Seattle. Groups like the National Employment Law Project have made a strong case for the expansion of just cause, characterizing it not just as a win for all workers but also as a racial justice issue for Black and Latinx workers.

The fate of this law, however, remains uncertain. The case was appealed on March 8, 2022. Given constitutional and preemption issues at play (particularly under the NLRA), SDNY’s analysis will be instructive. Just cause reformers and industry alike will surely be following the case closely as it advances to the Second Circuit.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

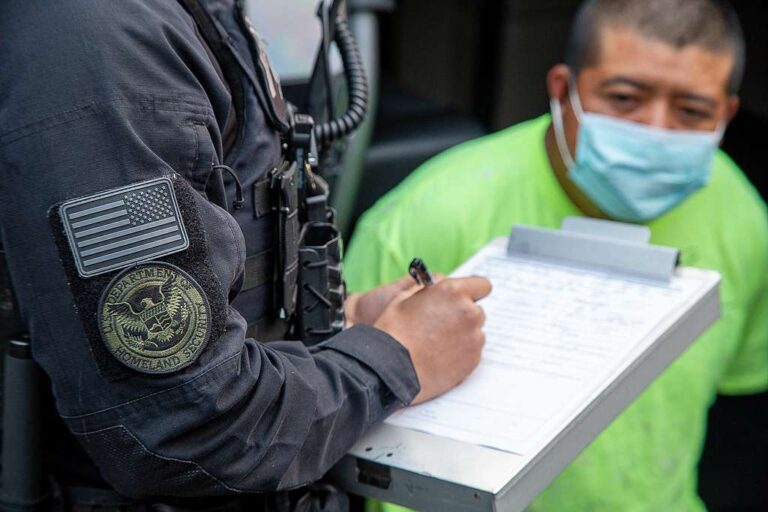

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.