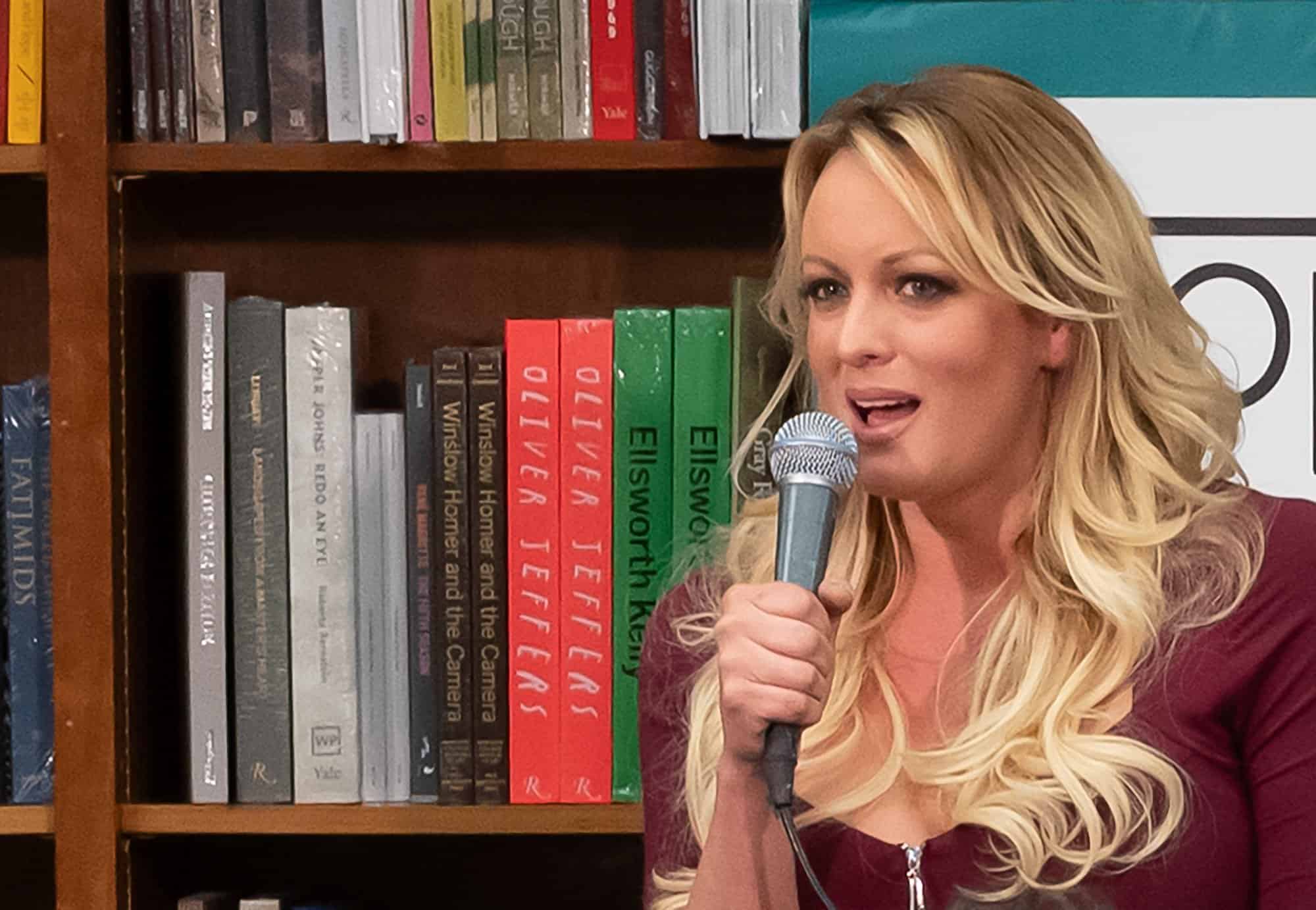

In February, Stormy Daniels published an op-ed arguing that exotic dancers should be “treated as freelancers, not employees.” In doing so, she criticized the California Supreme Court’s adoption of the “ABC test” in Dynamex. Under that test, a business that wants to classify a worker as an independent contractor must establish each of the following:

A) that the worker is free from control and direction of the hirer in connection with the performance of the work, both under the contract for the performance of such work and in fact;

(B) that the worker performs work that is outside the usual course of the hiring entity’s business; and

(C) that the worker is customarily engaged in an independent established trade, occupation, or business of the same nature as the work performed by the hiring entity.

That second factor, wrote Daniels, means that all California-based dancers, the overwhelming majority of whom are classified as independent contractors, are now employees; it is hard to argue that the usual course of a strip club’s business is anything other than selling strip-dances. Daniels argues that “forcing all dancers to become employees is not the answer” and that many prefer independent contractor status.

As Marissa has already discussed, Daniels’s op-ed is situated squarely within the ongoing debate over Dynamex. On one side are California Assemblywoman Lorena Gonzalez, who has introduced legislation to codify Dynamex, Soldiers of Pole, and other pro-union groups. On the other are Assemblywoman Melissa Melendez, who has tabled a competing bill to undo Dynamex, and the Independent Entertainer Coalition (IEC), a group of some 2,800 dancers who want to protect the “worker’s choice of deciding her employment status.” The clash between the two factions of exotic dancers is enlightening as a microcosm of the broader controversy around employment status and worker choice.

Exotic Dancer Misclassification Litigation

Lurking behind this debate are years of litigation over the employment status of exotic dancers. Since at least 2009, dancers have brought class actions under the FLSA and state laws against clubs in New York, Georgia, Michigan, Nevada, California, and Massachusetts, among other states. These lawsuits invariably accuse owners and managers of exploiting workers by misclassifying them as independent contractors while subjecting them to extensive control over the manner and means of work.

The typical case looks something like this: to work at a club on any given night, dancers are required to pay a “house fee” that ranges between $10 and $500, but typically hovers around $50. Once they’re in the door, they have little control over how much they earn because the clubs set prices for dances. They also impose strict rules over how dancers perform their work, including guidelines for interacting with customers and mandatory dress codes. At the end of the night, dancers do not receive a paycheck, but instead theoretically keep their tips. Yet clubs commonly require dancers to tip out a large portion of their earnings to other staff. On a slow night, it’s possible for a dancer to go home empty-handed or indebted to the club after paying out fees and tips. Finally, many clubs bar dancers from working for competitors, dictate their schedules by requiring them to work a minimum number of shifts, and impose fines for tardiness and absence.

In short, argue plaintiffs, strip clubs want it both ways: a tightly controlled workforce to which they can outsource all of the risk of loss without paying for employment benefits. Corporate consolidation in the industry has reportedly worsened those practices; in recent years a handful of companies have been buying up local clubs and imposing standardized contracts containing the abovementioned provisions.

The plaintiffs in these lawsuits have frequently prevailed, with courts determining that they are employees under the circumstances and ordering clubs to pay out millions of dollars in backpay. Notably, in 2016 Judge J. Harvey Wilkinson authored an opinion for the Fourth Circuit holding that a group of dancers were employees under the FLSA and Maryland state law despite “[t]he clubs[’] insist[ence that] they had very little control over the dancers.” In most instances, the affected strip clubs reclassified their dancers as employees.

That reclassification has met with mixed reviews. While some celebrate the protections and benefits that employee status affords, including the possibility of unionizing, others argue that reclassification has eaten into incomes. For example, one dancer writing for The Daily Caller in 2010 argued that, although employee status protects dancers from going home with zero or negative earnings, it limits their upside because the clubs can now claim a percentage of their commissions, presumably to offset employment costs. Thus, a dancer who took home $1400 working a 14-hour shift as an independent contractor might earn only $1100 as an employee.

Dancers After Dynamex

Hence the Dynamex debate. Since that decision came down in April, clubs throughout California have reclassified their dancers as employees, with some claiming that they have been “compelled by Court order to eliminate the independent contractor option” despite attempts to “protect[ their dancers’] right and freedom to be an independent contractor.” They have begun paying their dancers the minimum wage, but have also reportedly imposed quotas for sales of dances and drinks, and drastically cut commissions. Daniels and the IEC have cited these developments to argue that employee status strips dancers of control over their own schedules, curbs their freedom to work how and for whom they want, and reduces earnings by up to 70 percent. Consequently, they argue that workers should be able to choose their own employment status.

There is reason to push back on some of these claims. First, as this blog has repeatedly discussed, a change in status from independent contractor to employee does not necessitate greater control over the worker. Control is a factor that indicates an employment relationship, not a consequence thereof. Put another way, there is no legal doctrine preventing dancers from exercising control over their work lives if they are deemed employees.

Second, while employee status may result in some reduction in net income, it seems dubious that it should lead to such a drastic decline. That issue may soon be litigated. Recently, a class of dancers filed suit against a group of clubs owned by Déjà Vu, the largest strip club operator in the world, alleging that management unjustifiably slashed their earnings after reclassifying them as employees. The dancers argue that a new compensation structure, which has reduced their pay by hundreds of dollars per shift, was implemented in retaliation for prior misclassification litigation, pointing to managers’ statements that both reclassification and reduced pay were the result of “the lawsuits and ongoing demands by the suing dancers and their attorneys.”

Lastly, Daniels, the IEC, and other groups advocating for worker choice in California get one fundamental thing wrong: just like workers can’t waive their rights to overtime pay, minimum wage, or discrimination protection, they can’t waive their right to employee status by choosing to be independent contractors. In every test—from Dynamex’s ABC to the FLSA’s economic realities—it is the nature of the relationship between the worker and the putative employer that dictates employment status. In the dancers’ case, courts have resolved that question time and again in favor of employee status.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

In Today’s News and Commentary, the Supreme Court green-lights mass firings of federal workers, the Agricultural Secretary suggests Medicaid recipients can replace deported farm workers, and DHS ends Temporary Protected Status for Hondurans and Nicaraguans. In an 8-1 emergency docket decision released yesterday afternoon, the Supreme Court lifted an injunction by U.S. District Judge Susan […]

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.