Jason Vazquez is a staff attorney at the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 2023. His writing on this blog reflects his personal views and should not be attributed to the Teamsters.

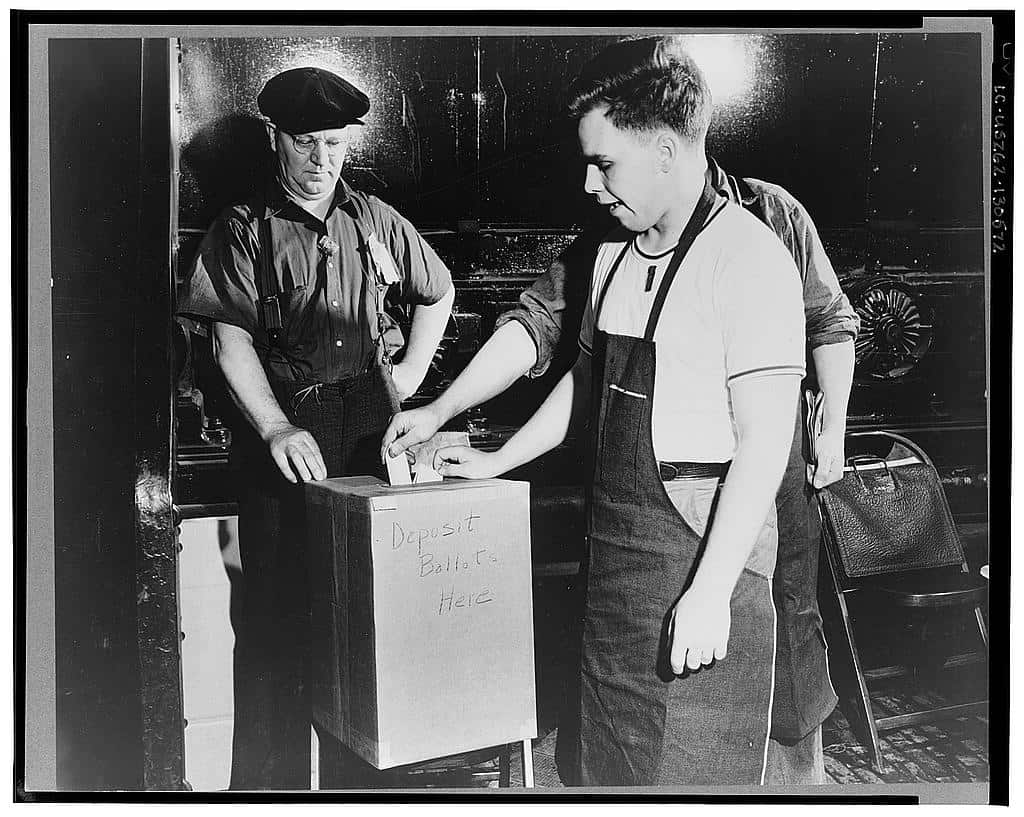

In a political economy characterized by private ownership of capital, transnational corporate consolidation, and immense concentrations of wealth, labor unions stand as uniquely democratic institutions. In sharp contrast to corporations — rigidly hierarchical, even tyrannical entities — federal law dictates that unions must be structured and operate democratically. In 1959, after a series of high profile hearings on criminal activities in the labor movement — in which Robert Kennedy and Jimmy Hoffa dramatically locked horns — Congress enacted the Labor Management Reporting and Disclosure Act (LMRDA) , which aims to purge corruption and racketeering from labor organizations. The Act mandates secret ballot elections for union officials, grants all members a legally enforceable right to vote, nominate candidates, run for office, and participate in union activities, protects members’ rights to speech and assembly, and requires that unions afford members a “full and fair hearing” before meting out internal discipline.

While the Act was largely motivated by antilabor impulses, there are reasons to embrace its protections. Democratic engagement — by activating and harnessing the militancy of the membership — is the foundation of labor power. Studies have highlighted that contracts negotiated by thoroughly democratic unions systematically tend to be stronger, as “union democracy increases union effectiveness in representing members’ interests and in mobilizing these members to support its collective bargaining agreements.” A number of academics and progressive thinkers have thus suggested that deepening the democratization of labor unions could help regenerate the embattled labor movement.

The U.S. labor movement took shape as the economy industrialized near the turn of the 20th century. The emerging labor organizations were decentralized and participatory, and labor activists — many of them socialists or communists — mobilized the membership to unleash militant, disruptive tactics, which subjugated powerful employers and organized millions of working people. The Gilded Age judiciary sough to fiercely repress this activity, issuing hundreds of injunctions to block strikes, work disruption, and other protest activities, which only intensified labor’s radical orientation. During the New Deal era, in an effort to alleviate disruptive labor strife, head off labor militancy, and channel labor disputes into an impartial administrative body, Congress codified basic labor rights into federal law. In the following decades, with these protections in place, unions expanded their size and authority and deepened their professionalization and bureaucratization. Some began to prioritize entrenchment over expansion. Compounding the pressure, as the neoliberal regime has dismantled organized labor, national unions have increasingly merged and consolidated in recent years. These currents have forged a modern union movement that is highly centralized and institutionalized, dominated by a handful of national organizations.

While large labor organizations may be necessary to countervail the enormous concentrations of private capital, the reality is that, notwithstanding significant efforts in recent years to expand their participatory outreach, today’s union remain plagued by democratic deficiencies. Research suggests that national unions, while “firmly democratic,” exhibit tendencies of oligarchies or autocracies. Barely a handful of the largest unions use a direct voting system, and it is not uncommon that top officer elections in many major unions are barely contested or uncontested. In fact, a challenger has not toppled an incumbent president in any of the largest unions in decades. While unions ‘ federated structure means that local affiliates are often more closely engaged with the membership than the national organization, there are indications that the dearth of democratic engagement at the highest levels has given rise to a disconnect between leaders and members — and working people more broadly. In 2016, for instance, while many members supported Bernie Sanders’ populist message, the executive boards of most major unions endorsed Hillary Clinton in the Democratic primary. And in the general election, a significant share of union members in crucial swing states sidestepped leaders’ endorsements and voted for Donald Trump. Labor leaders subsequently conceded they had misapprehended the depth of disillusion and frustration among their membership.

At bottom, the struggle for organized labor is a struggle for working people to control their lives; a struggle, in other words, for democracy. In embracing participatory democracy, unions enhance their capacity to democratize not only the workplace but the broader political economy.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

March 4

the NLRB and Ex-Cell-O; top aides to Labor Secretary resign; Attacks on the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service

March 3

In today’s news and commentary, Texas dismantles their contracting program for minorities, NextEra settles an ERISA lawsuit, and Chipotle beats an age discrimination suit. Texas Acting Comptroller Kelly Hancock is being sued in state court for allegedly unlawfully dismantling the Historically Underutilized Business (HUB) program, a 1990s initiative signed by former Governor George W. Bush […]

March 2

Block lays off over 4,000 workers; H-1B fee data is revealed.

March 1

The NLRB officially rescinds the Biden-era standard for determining joint-employer status; the DOL proposes a rule that would rescind the Biden-era standard for determining independent contractor status; and Walmart pays $100 million for deceiving delivery drivers regarding wages and tips.

February 27

The Ninth Circuit allows Trump to dismantle certain government unions based on national security concerns; and the DOL set to focus enforcement on firms with “outsized market power.”

February 26

Workplace AI regulations proposed in Michigan; en banc D.C. Circuit hears oral argument in CFPB case; white police officers sue Philadelphia over DEI policy.