Jason Vazquez is a staff attorney at the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 2023. His writing on this blog reflects his personal views and should not be attributed to the IBT.

The principle of democracy is exalted by many as a central feature of the U.S. constitutional regime that has, at least in the public imagination, secured us an exceptional degree of liberty, equality, and prosperity. The disquieting reality that the framers of the Constitution carefully circumscribed popular influence over the mechanisms of government and designed a political economy that operates as more of an oligarchy than a republic has done little to diminish the pervasive conviction among many that the United States remains a nation devoted to, predicated on, and characterized by ideals of democratic empowerment. As progressive thinkers have long theorized, however, the conception of democracy existing in the public imagination is incomplete, for it is premised on a superficial distinction between the “private” and the “public” sphere. In reality, the promise of democracy is greatly diminished, perhaps even rendered illusory, if confined solely to the electoral realm. To create a political economy truly embodying democratic ideals, then, popular participation must penetrate into the hearts of the powerful, private institutions wielding tremendous authority to shape the socioeconomic conditions around us. In short, if we wish to live in a democratic society, we must democratize the corporation.

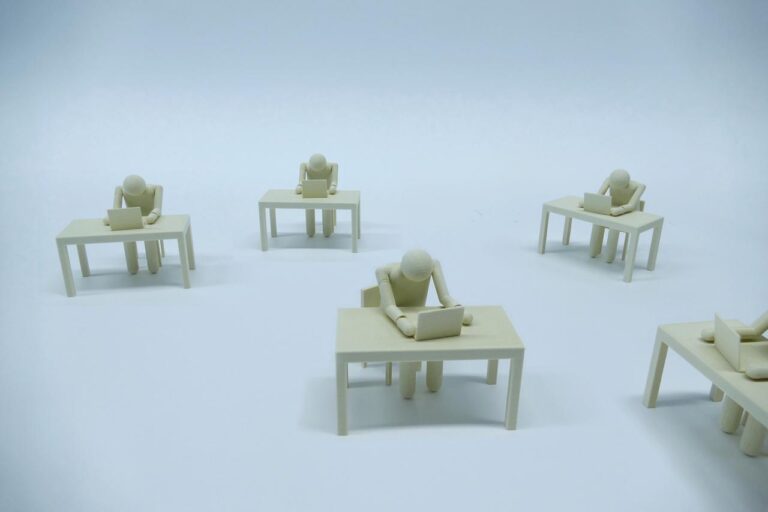

At its core, democracy rests on the ideal that individuals should be empowered to exercise a meaningful measure of influence over the decisions that affect their lives. Yet many of the most consequential policies shaping the U.S. political economy are formulated not in the nation’s ostensibly representative legislative chambers or government offices but rather by unelected and self-serving economic elite convening in fancy corporate boardrooms. Corporate leaders make decisions about employment, compensation, production, investment, and resource-allocation that have enormous implications for broader socioeconomic conditions. And this should be concerning in a nation that purports to prioritize democracy, given that the corporation is, at its core, a deeply autocratic institution. Indeed, a corporation’s internal management structure is a rigidly hierarchical one that vests ultimate authority in the hands of extravagantly wealthy executives and investors, which affords them nearly unlimited power to control the lives of the employees whose toil generates the firm’s resources and profits as well as social conditions in the communities in which they operate. In light of corporations’ power over our lives, then, so long as they remain autocratic, it is difficult to view our society as anything but.

A vision of democratic economic institutions has deep roots in the labor movement. In fact, unions in the 19th and 20th centuries routinely advocated for worker control of factories. Establishing industrial democracy was one of the original objectives of the Industrial Workers of the World, for instance, and the Knights of Labor enshrined the establishment of cooperative firms as a priority in their constitution. Even today, democratic control of corporations remains popular across ideological lines.

The concept of economic democracy is a simple and intuitive one. At bottom, it requires that a firm’s decisionmaking must, to some meaningful degree, be controlled or influenced by its employees. The ideal serves as more of an orienting principle than a specific policy prescription, and many attractive proposals to democratize corporations have been suggested. Expanding collective bargaining, for example, is one promising avenue. Labor unions, which are themselves democratically structured, redistribute power within a firm from capital to labor and thus have a democratizing impact on the workplace (although, to be sure, their capacity to dramatically transform the economic order may be limited). Another path toward economic democracy could come in the form of a powersharing arrangement between owners and employees. Such proposals range from establishing representative institutions to govern corporations to mandating that workers elect some portion of the firm’s board of directors. A limited version of the latter approach is practiced extensively and successfully in many European nations. The most fundamentally transformative model would, of course, be some form of worker cooperative or self-directed enterprise, in which employees own the firm and either entirely select the board of directors or, in the most comprehensively democratic enterprises, each participate equally in the firm’s decisionmaking. Thousands of such entities exist around the world, including hundreds in the United States. Some are impressively large and successful.

Democratizing economic institutions has the potential to vastly mitigate the inequality, displacement, and suffering inherent to shareholder capitalism. This is because when workers control management, production, and investment decisions, they tend to resist the temptation to pay top executives hundreds of times more than employees, spend trillions of dollars to inflate stock values, or outsource their own jobs to labor markets more susceptible to exploitation. To the contrary, research reveals that workplace democracy, particularly the worker cooperative model, enhances wages, economic security, job satisfaction, and productivity; reduces income disparities, unemployment, and crime; and even fosters local economic development. Indeed, the average wage paid at a worker co-op in the United States is more than double the federal minimum wage and, astoundingly, the vast majority report a top-to-bottom pay ratio of 2:1. By way of contrast, the average CEO in a traditionally structured U.S. corporation rakes in a salary more than 300 times that of an ordinary employee.

Moreover, beyond its implications with respect to distributive justice, economic democracy is to a large extent inextricable from political democracy. Private control of corporations has produced such exorbitant disparities in wealth as to, in a system in which money is equated with speech, largely preclude any meaningful political equality. Progressive thinkers have long perceived the danger that private control of such vast economic resources poses to the vitality of the political system. In the early 20th century, for example, future Supreme Court Justice Louis Brandeis, regretfully observing “the contrast between our political liberty and our industrial absolutism,” concluded that “industrial democracy should ultimately attend political democracy.” Similarly, the Walsh Commission, ordained by Congress in 1912 to examine labor conditions, explained in its final report that “political democracy can exist only where there is industrial democracy,” and thus recommended “the rapid extension of the principles of democracy to industry.” And in formulating the National Labor Relations Act of 1935, Senator Robert Wagner was in part animated by the nexus existing between industrial and electoral self-determination, insisting that “democracy cannot work unless it is honored in the factory as well as the polling booth.”

To be sure, it remains uncertain how democratized firms might operate and interact within a ferocious regime of competitive capitalism. In other words, corporate democracy will not entirely eradicate the destructive pressures of commercial competition, and complete democratization of the economic order will likely require transcending even employee ownership of private firms. But at the very least, democratizing corporations will enable working people to more meaningfully control their own lives. All told, if we cherish the principle of democratic rule and wish to exist in a free and equal society, we must rectify the absurd contradiction of democracy in politics and tyranny in the economy.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

December 13

In today’s News & Commentary, the Senate cleared the way for the GOP to take control of the NLRB next year, and the NLRB classifies “Love is Blind” TV contestants as employees. The Senate halted President Biden’s renomination of National Labor Relations Board Chair Lauren McFerran on Wednesday. McFerran’s nomination failed 49-50, with independents Joe […]

December 11

In today’s News and Commentary, Biden’s NLRB pick heads to Senate vote, DOL settles a farmworker lawsuit, and a federal judge blocks Albertsons-Kroger merger. Democrats have moved to expedite re-confirmation proceedings for NLRB Chair Lauren McFerran, which would grant her another five years on the Board. If the Democrats succeed in finding 50 Senate votes […]

December 10

In today’s News and Commentary, advocacy groups lay out demands for Lori Chavez-DeRemer at DOL, a German union leader calls for ending the country’s debt brake, Teamsters give Amazon a deadline to agree to bargaining dates, and graduates of coding bootcamps face a labor market reshaped by the rise of AI. Worker advocacy groups have […]

December 9

Teamsters file charges against Costco; a sanitation contractor is fined child labor law violations, and workers give VW an ultimatum ahead of the latest negotiation attempts

December 8

Massachusetts rideshare drivers prepare to unionize; Starbucks and Nestlé supply chains use child labor, report says.

December 6

In today’s news and commentary, DOL attempts to abolish subminimum wage for workers with disabilities, AFGE reaches remote work agreement with SSA, and George Washington University resident doctors vote to strike. This week, the Department of Labor proposed a rule to abolish the Fair Labor Standards Act’s Section 14(c) program, which allows employers to pay […]