Mark Harcourt is a professor in the Waikato Management School, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand and author of over 60 articles, many of them about unions and employment relations.

Gregor Gall is a visiting professor at Leeds University, UK, and the author of more than 100 academic articles and 10 books about unions and employment relations issues.

Margaret Wilson is an emeritus professor, former Dean and Professor of Te Piringa/Waikato Law Faculty, University of Waikato, Hamilton, New Zealand, and former Minister of Labour and Attorney General in the Clark Government, 1999-2008.

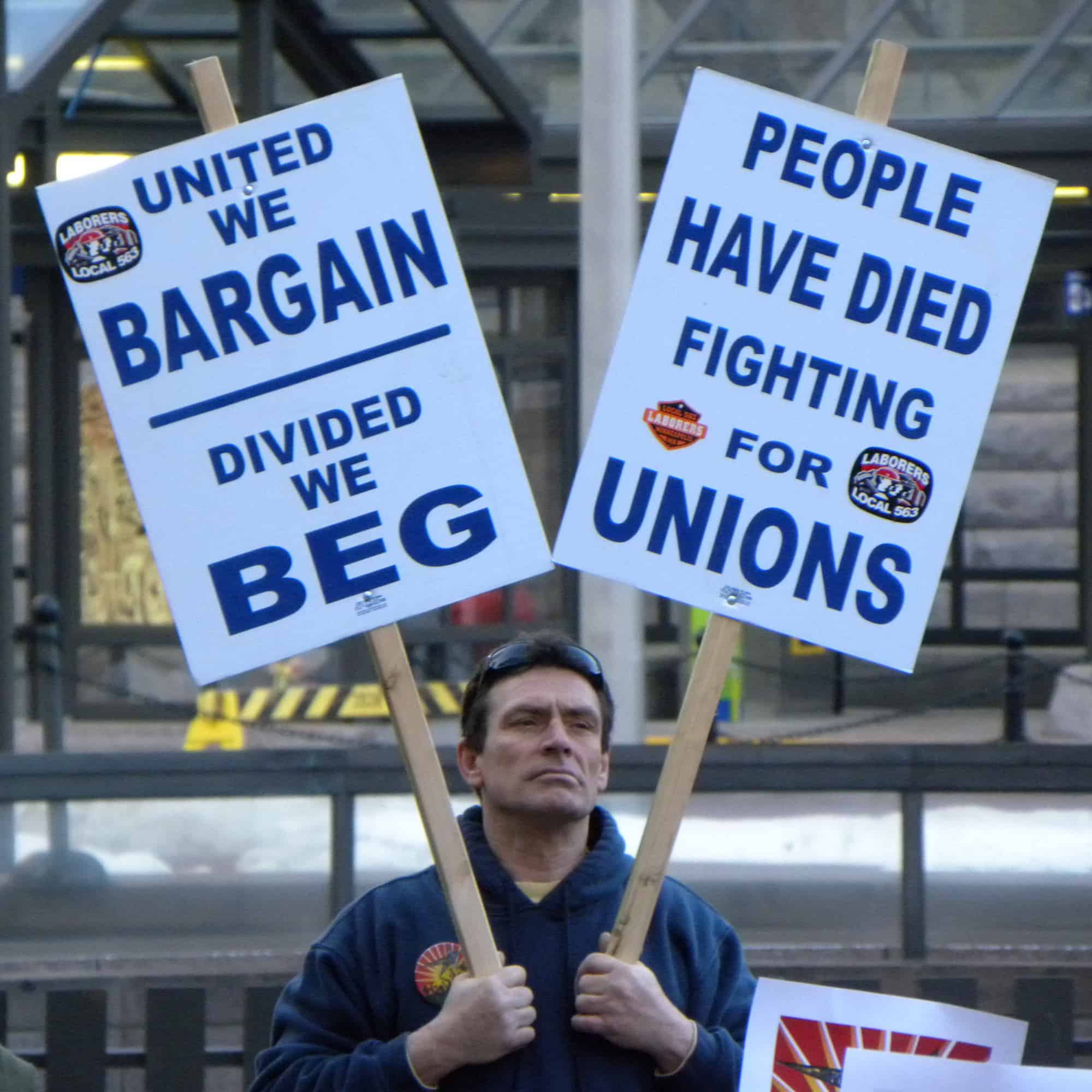

Unions have traditionally had a strong levelling effect on incomes, transferring money from capital to labour, particularly to the low-waged. Thus, falling union membership and collective bargaining coverage over the last 40 years have been strongly linked to widening disparities, particularly in the US, Britain, and New Zealand. Yet, approximately half the workforce in these English-speaking countries says it still wants union representation. And, if anything, workers now favour unions more than 20 years ago. However, organising workers has been problematic, not least because of the nature of the NLRA system and the employer opposition it allows.

In this article, we propose that the US adopt a union default policy to revive collective bargaining, counterbalance corporate power, and reduce income disparities. We, Mark Harcourt, Gregor Gall, Margaret Wilson, are leading experts on the union default, having completed two studies and written a number of articles on the subject. Mark and Margaret are professors at Waikato University in New Zealand; Gregor is a professor at Leeds University in the UK. Margaret has also been the Minister of Labour, Attorney General, and Speaker of the House (parliament) in New Zealand. Our research shows that a union default can be fitted into an existing employment relations legal framework, and that the idea is likely to be popular with the public.

What is a union default? A union default would default all employees within a given bargaining unit to union membership via an automatic enrollment process. Once enrollment was completed, employees would be free to opt out if they wished.

Is this compatible with freedom of choice? A default would preserve the freedom not to associate with a union as workers would not be obliged to remain members. And, a default could greatly enhance and strengthen the freedom to associate with a union by making it a lot easier for unions to organise new workplaces.

How would it work in the US? A default would operate in two phases. In phase one, a union would recruit at least 10% of a bargaining unit as members. The NLRB would then certify the union to only bargain collectively for its members. The certified union would also be granted default status. As a result, all workers in the bargaining unit, and any worker hired later, would be defaulted to membership of this union. However, each worker would still have a right to opt out for an individual contract with their employer.

If a second union also recruited 10% or more members in the same bargaining unit, it too would be certified to only bargain for its members. But, only the union with the greatest membership in the bargaining unit would be awarded default status.

In phase two, a union already certified in phase one could apply to become the sole and exclusive bargaining agent for union and non-union workers in the bargaining unit. The NLRB would supervise a ballot, with all workers in the bargaining unit entitled to vote. If a majority of those voting supported the idea, the applicant union would then be granted sole and exclusive representation rights.

How would workers be defaulted into a union? The employer would carry out a simple, standardised electronic enrolment process, established by the NLRB for all such situations. For example, a worker would receive a standardised message via text and email, announcing his/ her auto-enrolment, and a similar later notification of the opting out process (e.g., click on a weblink and fill out a short form). Opting out would not be possible, until automatic enrolment had been completed. The certified union could also be empowered to issue improvement notices against employers who failed to comply with the enrolment process. Failure to comply with an improvement notice would then be grounds for an unfair labor practice penalty, administered by the NLRA.

Why would employers bargain in good faith with newly certified unions? Given the history of employer opposition to bargaining, Canadian-style first contract arbitration would be appropriate. This option would still allow the parties to bargain collectively for their own first agreement. However, if they failed to settle within a strict time-frame (e.g., 3 months), a first agreement would be imposed via an NLRB-supervised arbitration process. A second solution could involve a protected right to strike over union recognition, available to all the members of the relevant certified union.

If workers can opt out, wouldn’t many do so? In right-to-work states, recruiting and retaining members is difficult when workers can ‘free-ride’. How would a union default change this? While free-riding would still happen, it would be significantly reduced by the default effect. Past research in many fields (e.g., medicine, marketing, and insurance) shows when an option is set as the default it greatly increases the chances that particular option will be chosen. Thus, individuals tend to stick with defaults, whatever they may be. They do so for four main reasons. First, individuals tend to stay with a status quo default because of the forces of inertia, indecisiveness and procrastination, especially where they are unsure of the costs and benefits of alternatives. Second, individuals often interpret defaults as norms they should follow: what is socially acceptable or what is preferred by a majority of their fellows. Third, defaults are often used as starting points for judging the ‘gains’ and ‘losses’ of any particular choice. Since individuals are much more averse to ‘losses’ than attracted to equivalent ‘gains’, they generally prefer to minimise their ‘losses ‘by sticking with a status quo default. Finally, the switching (e.g., time and trouble) costs of making a choice often dissuade individuals from doing so.

Would a union default be compatible with more centralised and effective bargaining? A union default combined with a low threshold of membership support (e.g., 10%) would make it easier to organise larger bargaining units, comprised of mainly small businesses with hard-to-contact employees. The NLRB would have to re-define the concept of the ideal bargaining unit, relying on new principles. These could include: the preferences of the union (as a freedom of association issue), economies of scale in union servicing, and community of interest across, for example, a shopping mall, a franchise, a supply chain, or an industry.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 25

OSHA workplace inspections significantly drop in 2025; the Court denies a petition for certiorari to review a Minnesota law banning mandatory anti-union meetings at work; and the Court declines two petitions to determine whether Air Force service members should receive backpay as a result of religious challenges to the now-revoked COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

February 24

In today’s news and commentary, the NLRB uses the Obama-era Browning-Ferris standard, a fired National Park ranger sues the Department of Interior and the National Park Service, the NLRB closes out Amazon’s labor dispute on Staten Island, and OIRA signals changes to the Biden-era independent contractor rule. The NLRB ruled that Browning-Ferris Industries jointly employed […]

February 23

In today’s news and commentary, the Trump administration proposes a rule limiting employment authorization for asylum seekers and Matt Bruenig introduces a new LLM tool analyzing employer rules under Stericycle. Law360 reports that the Trump administration proposed a rule on Friday that would change the employment authorization process for asylum seekers. Under the proposed rule, […]

February 22

A petition for certiorari in Bivens v. Zep, New York nurses end their historic six-week-strike, and Professor Block argues for just cause protections in New York City.

February 20

An analysis of the Board's decisions since regaining a quorum; 5th Circuit dissent criticizes Wright Line, Thryv.

February 19

Union membership increases slightly; Washington farmworker bill fails to make it out of committee; and unions in Argentina are on strike protesting President Milei’s labor reform bill.