Sophia is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

The Harvard Graduate Students Union (HGSU) and Harvard University are six months into negotiations over their third collective bargaining agreement. Like many other grad unions engaged in contract bargaining, HGSU is facing stiff opposition — the University has issued rejection after rejection after rejection of the Union’s proposals. At the same time, anxiety over the possible overturning of Columbia — the 2016 National Labor Relations Board decision that granted graduate student workers at private universities the right to unionize — pervades grad student organizing spaces across the country. In this post I argue that a sectoral bargaining system for higher education would address the weak position many grad student unions occupy when bargaining at the individual campus level, while offering a host of benefits to other university employees and higher education as a whole.

The Saga of Graduate Student Worker Classification

Graduate student unionization began in the late 1960s and 70s at the University of Wisconsin-Madison where graduate student workers negotiated the country’s first collective bargaining agreement between graduate student workers and university administrators. This CBA was a momentous occasion for graduate student workers at public universities where state law governs public sector collective bargaining. The road to unionization for graduate students at private universities, on the other hand, was much more tortuous.

For over fifty years, the Board has vacillated on the question of whether to classify graduate student workers at private schools as statutory “employees” under the National Labor Relations Act. In Leland Stanford Junior University (1974), the Board held that graduate student assistants at private universities were “not employees within the meaning of Section 2(3) of the Act.” The Board upheld this decision excluding student workers from the statutory definition of employees for 26 years until New York University (2000) where it held that some university graduate student assistants were in fact employees covered under the Act. Then, in Brown University (2004), the Board reverted back to its former position, arguing that graduate students “have a predominately academic, rather than economic, relationship with their school,” so are therefore not statutory employees. Flipping positions once again, the Board decided in Columbia University (2016) that “student assistants who have a common-law employment relationship with their university are statutory employees under the Act.”

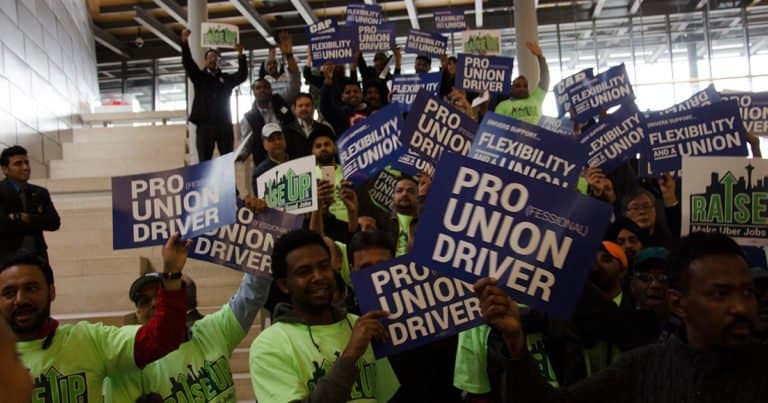

Though Columbia remains the law today, its status is viewed by many as precarious given the Board’s shifting attitude towards graduate student workers, which begs the question: What would a future look like where grad student unions didn’t have to rely on the whims of the Board? Today, over 1 in 3 grad student workers is represented by a union. Since 2012, the number of graduate student worker union members has risen from about 64,400 to over 150,100 in 2024 — a 133% increase in union membership. Pro-labor advocates should take advantage of this momentum to push for higher education sectoral bargaining — a system of collective bargaining where all workers within a given sector are covered by the same contract setting wages, hours, benefits, and other terms and conditions of employment.

Securing the Future of Grad Student Unions and Higher Education Through Sectoral Bargaining

A system of sectoral bargaining would offer a host of benefits. First, by extending collective bargaining coverage to all workers in the sector — regardless of their classification as employees — a system of collective bargaining for graduate student workers could relieve anxiety that the Board might strip them of their right to unionize at any time. In addition, sectoral bargaining could benefit grad unions by frustrating university administration efforts to outsource labor. For example, in an effort to weaken the Student Workers of Columbia by reducing the number of dues-paying bargaining unit members, Columbia University solicited non-Columbia doctoral candidates for positions historically filled by unionized grad student workers. In the higher education context, an industry-wide agreement could stipulate that universities must offer teaching positions to their own students first before seeking students from other institutions. In addition, by extending the reach of the collective bargaining agreement to all workers in the sector, a sectoral system would reduce the incentive for Universities to outsource in the first place.

For the same reason, sectoral bargaining could help better the lives of contingent faculty members. American universities increasingly resemble fissured workplaces due to the dramatic shift in hiring practices over the last four decades: The percentage of academic employees who are full-time tenured or on the tenure-track dropped from 70% in the 1980s to just 32% today. The host of struggles contingent faculty members experience is well reported, including abysmal wages, job insecurity, inadequate access to benefits, and lack of respect. Sectoral bargaining would empower contingent faculty — individuals who occupy an especially precarious and weak position in the university hierarchy when speaking alone — to band together and even bargain for what the Connecticut State Universities American Association of University Professors calls the “Contingent Faculty Bill of Rights.” Bargaining at the sectoral level, as opposed to the enterprise level alone, would prevent universities from constantly seeking cheaper labor elsewhere — a cycle which inevitably leads to a race to the bottom for wages.

Third, sectoral bargaining could benefit universities as a whole — students, faculty, staff, and administration alike — by increasing the overall bargaining power of the higher education industry such that they could maintain integrity despite the bitterest of political attacks. For instance, academic workers, using their collective voice, could bargain for a baseline level of academic freedom that every private university must honor, which would give higher education employees a sort of just cause protection for certain expressive speech. Establishing an industry-wide understanding of academic freedom could also, in turn, strongly incentivize university administrations to hold the line against political attacks and resist capitulation.

While sectoral bargaining is not required under federal law, it can be established through voluntary agreements made by unions and employers. Alternatively, if a future Board reverses Columbia and holds that grad students are not statutory employees, states could establish sectoral bargaining systems for those workers (and any others excluded from federal coverage). However, as Benjamin Sachs and Sharon Block note, designing an effective sectoral bargaining scheme requires making decisions on a number of system-design questions: how to define a sector, who should sit at the bargaining table, the scope of bargaining, what to do when an impasse occurs, and the enforcement mechanism for when a contract violation occurs.

Although developing a higher education sectoral bargaining system would be a complex and, quite frankly, daunting process, efforts in sector-wide coordinated activity have already begun: The American Association of University Professors aims to promote economic security and academic freedom for all higher education professionals, and Higher Ed Labor United invites university and college workers from across the country and across job categories to unite and advocate for a future where higher education is treated and funded as a social good and universal right. Though seemingly modest stepping stones, these initiatives demonstrate that there is a collective desire to ensure that university administrations treat their workers right and that higher education remains committed to free inquiry.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

December 22

Worker-friendly legislation enacted in New York; UW Professor wins free speech case; Trucking company ordered to pay $23 million to Teamsters.

December 21

Argentine unions march against labor law reform; WNBA players vote to authorize a strike; and the NLRB prepares to clear its backlog.

December 19

Labor law professors file an amici curiae and the NLRB regains quorum.

December 18

New Jersey adopts disparate impact rules; Teamsters oppose railroad merger; court pauses more shutdown layoffs.

December 17

The TSA suspends a labor union representing 47,000 officers for a second time; the Trump administration seeks to recruit over 1,000 artificial intelligence experts to the federal workforce; and the New York Times reports on the tumultuous changes that U.S. labor relations has seen over the past year.

December 16

Second Circuit affirms dismissal of former collegiate athletes’ antitrust suit; UPS will invest $120 million in truck-unloading robots; Sharon Block argues there are reasons for optimism about labor’s future.