Tascha Shahriari-Parsa is a government lawyer enforcing workers’ rights laws. He clerked on the Supreme Court of California after graduating from Harvard Law School in 2024. His writing on this blog reflects his personal views only.

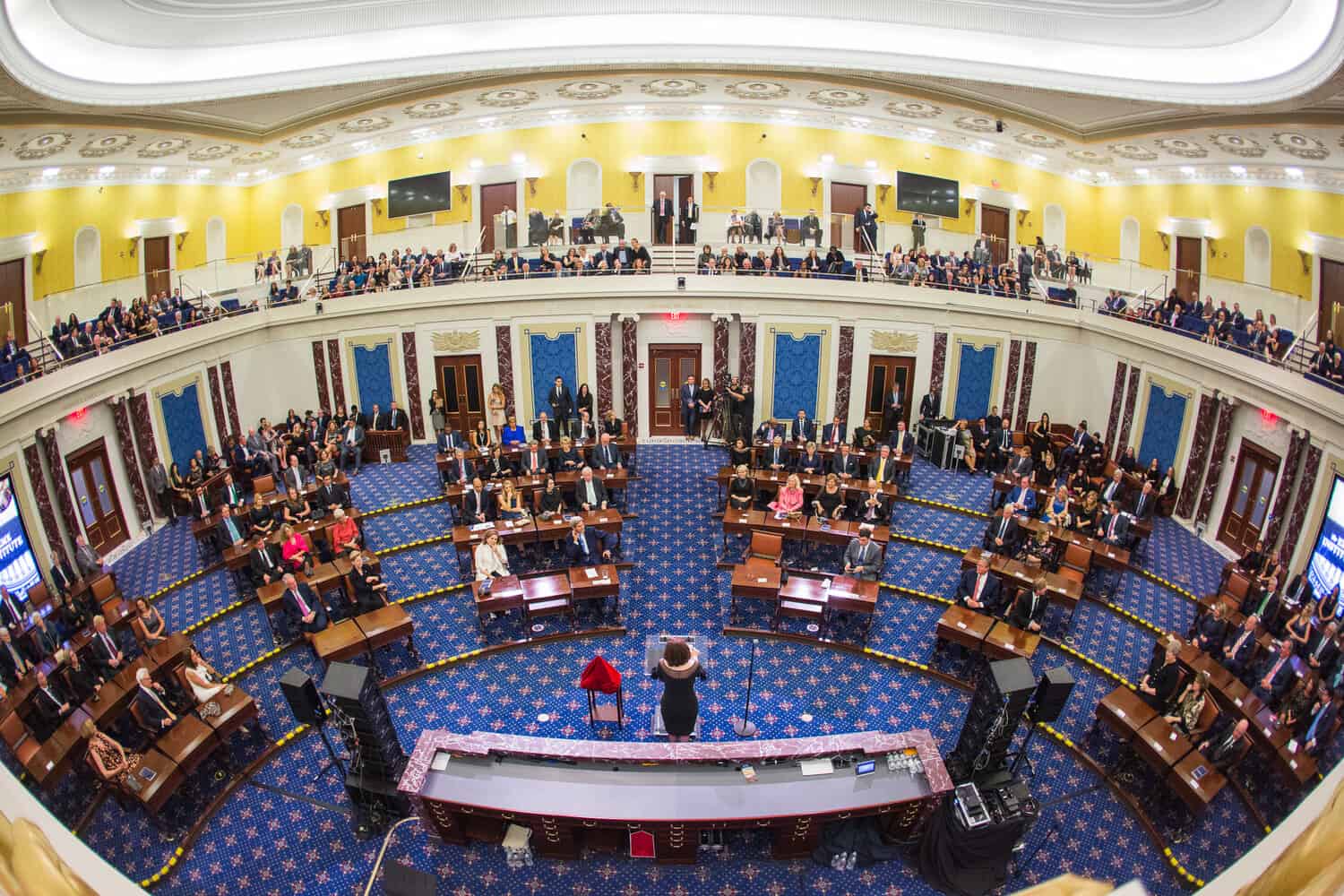

Earlier this month, the Senate Health, Education, Labor and Pensions (HELP) Committee held a hearing on the bipartisan Faster Labor Contracts Act (FLCA). The bill is virtually identical to the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act’s First Contract Arbitration provision, with one crucial difference: it has a chance of becoming law in today’s Congress. Whereas the PRO Act had no Republican sponsors in the Senate and only three in the House, the FLCA already has twelve Republican sponsors in the House and two in the Senate.

Is this evidence of a genuine pro-worker turn within a faction of the MAGA right? A moment of political opportunism? The early stirrings of a cross-partisan realignment? These are worthwhile questions. But for the purposes of this post, I’m bracketing the confounding politics of bipartisan reform to focus on the bill’s substance.

As its name suggests, the FLCA responds to a widely appreciated problem: it takes far too long for unions to negotiate their first contract. Two years after forming, 43% of new unions still lack an agreement. Take the Starbucks workers who voted for a union in Buffalo in December 2021, or the Amazon warehouse workers who unionized in Staten Island in April 2022 — years later, neither have contracts.

That’s because under existing law, employers like Starbucks and Amazon can deploy endless delay tactics without consequence. Though the NLRA imposes a duty to bargain, Board orders enforcing that duty aren’t self-enforcing and carry no penalties — making it a winning strategy for employers to dodge bargaining while the Board chases them in circles. As John Logan explains:

Amazon’s obstructionism is not simply about denying a collective bargaining agreement to these workers. Rather, it is intended to send a signal to hundreds of thousands of other Amazon workers who might be considering trying to form a union: The company will never stop fighting unionization, and even if you withstand a blistering Amazon anti-union campaign, the company and its scores of Morgan Lewis lawyers will do everything possible to make sure you never get a first collective agreement.

To fix this, the FLCA would set default timelines for negotiating first contracts. Once workers unionize, the employer has ten days to begin bargaining. After 90 days, the parties can continue bargaining, but either party may also request mediation.

If 30 days of meditation pass without a contract, bargaining can continue — but either party may now elect to submit the dispute to a three-person arbitration panel. One arbitrator is selected by each party; the third is mutually chosen by both or else by FMCS. The panel will consider things like the employer’s size and financial status, employee cost of living, and comparator wages, and it will draft a 2-year collective bargaining agreement, which is binding “unless amended during such period by written consent of the parties.”

I’ve already written about why this system works: the threat of arbitration gives workers leverage, pressures both sides to reach agreements, and tends to result in higher wages. The FLCA will also encourage new organizing by effectively guaranteeing a contract on the horizon for those who do.

Here, I want to address the most common substantive objection to the FLCA: that we shouldn’t place federal bureaucrats in charge of contract negotiations. Whether that view stems from faith in free contracting, a commitment to industrial democracy, or skepticism about an outside adjudicator’s ability to determine what’s best for a specific workplace, I take it that many across the political spectrum (though not all) are wary of arbitrators deciding labor contracts.

But this critique misunderstands how first-contract arbitration works: as a rarely used last resort. As Matt Bruenig explains, the 70% of first contract negotiations that currently go well will be virtually unaffected by the FLCA. The threat of arbitration just helps get the other 30% moving.

That’s because neither party wants to arbitrate. Arbitration has fees. Arbitration introduces uncertainty. And, compared to unions and employers, arbitrators have less “intimate knowledge” about the specific workplace that helps produce a workable agreement.

These are similar to the downsides of a civil trial. And only 1% of civil cases in federal court go to trial. Just as the threat of trial encourages fair settlements, especially between parties with otherwise unequal bargaining power, the threat of arbitration brings employers to the table in earnest. But almost always, the trial or arbitration does not transpire.

The evidence backs this up. British Columbia offers a useful comparison: its labor code allows first contracts to be decided by an arbitrator if bargaining and mediation fail. Over a thirty-year period, only half of one percent of first contracts were imposed by an arbitrator. (The rate is higher in other Canadian jurisdictions that skip mediation — another reason to think the FLCA, which requires mediation, was thoughtfully drafted.)

What’s more, even in the rare case where the arbitrator steps in, they’re penciling in a provisional agreement. Instead of the current default — no agreement, a.k.a. whatever the employer wants — the arbitrator supplies a baseline for continued bargaining and a fallback in case negotiations break down. If the arbitrator gets something wrong, the parties can amend — or even fully scrap — the arbitrator’s terms.

Finally, when it comes to bureaucratic intrusion, the status quo is worse. Instead of keeping employers and unions focused on bargaining, as the FLCA would do, the current rules force the parties to continually return to the Board to quarrel — not over substance, but over the meta-question of whether their negotiations are proceeding in good faith. It’s like arguing about arguing — an unproductive distraction. (Once the Board applies for enforcement of a bargaining order, we might say the parties start arguing about arguing about arguing.) By leveraging the threat of arbitration, the FLCA nudges parties to bargain in good faith instead of bringing in a third party to directly micromanage negotiating behavior.

At bottom, the FLCA doesn’t restrict voluntary bargaining or replace it with government-imposed deals. It simply introduces the soft but credible threat of arbitration to deter endless dilly-dallying and “encourage[e] the practice and procedure of collective bargaining,” as the 1935 Congress expressly intended. Who could object to that?

To be sure, there is something discordant about pushing for faster contracts while the executive branch dismantles the NLRB and FMCS — the very agencies the FLCA depends on to carry out its promise. And the worry always looms that smaller fixes might sap momentum for broader reform. The AFL-CIO is thus rightfully leveraging the attention on the FLCA to decry executive union busting and reassert the need for passing the PRO Act in its entirety.

And yet, the federation’s message to the Senate HELP Committee is clear: “mark up this bill.” In addition to “solv[ing] one problem confronting workers every year,” the FLCA would help expand the base of organized workers who can continue fighting for comprehensive labor law reform in the years to come.

If there’s one thing that takes longer than bargaining a first contract, it’s passing federal labor law reform. By enacting the Faster Labor Contracts Act, Congress can make progress on both problems at once.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

October 26

California labor unions back Proposition 50; Harvard University officials challenge a union rally; and workers at Boeing prepare to vote on the company’s fifth contract proposal.

October 24

Amazon Labor Union intervenes in NYS PERB lawsuit; a union engages in shareholder activism; and Meta lays off hundreds of risk auditing workers.

October 23

Ninth Circuit reaffirms Thryv remedies; unions oppose Elon Musk pay package; more federal workers protected from shutdown-related layoffs.

October 22

Broadway actors and producers reach a tentative labor agreement; workers at four major concert venues in Washington D.C. launch efforts to unionize; and Walmart pauses offers to job candidates requiring H-1B visas.

October 21

Some workers are exempt from Trump’s new $100,000 H1-B visa fee; Amazon driver alleges the EEOC violated mandate by dropping a disparate-impact investigation; Eighth Circuit revived bank employee’s First Amendment retaliation claims over school mask-mandate.

October 20

Supreme Court won't review SpaceX decision, courts uphold worker-friendly interpretation of EFAA, EEOC focuses on opioid-related discrimination.