Tristan Bird is a student at Harvard Law School.

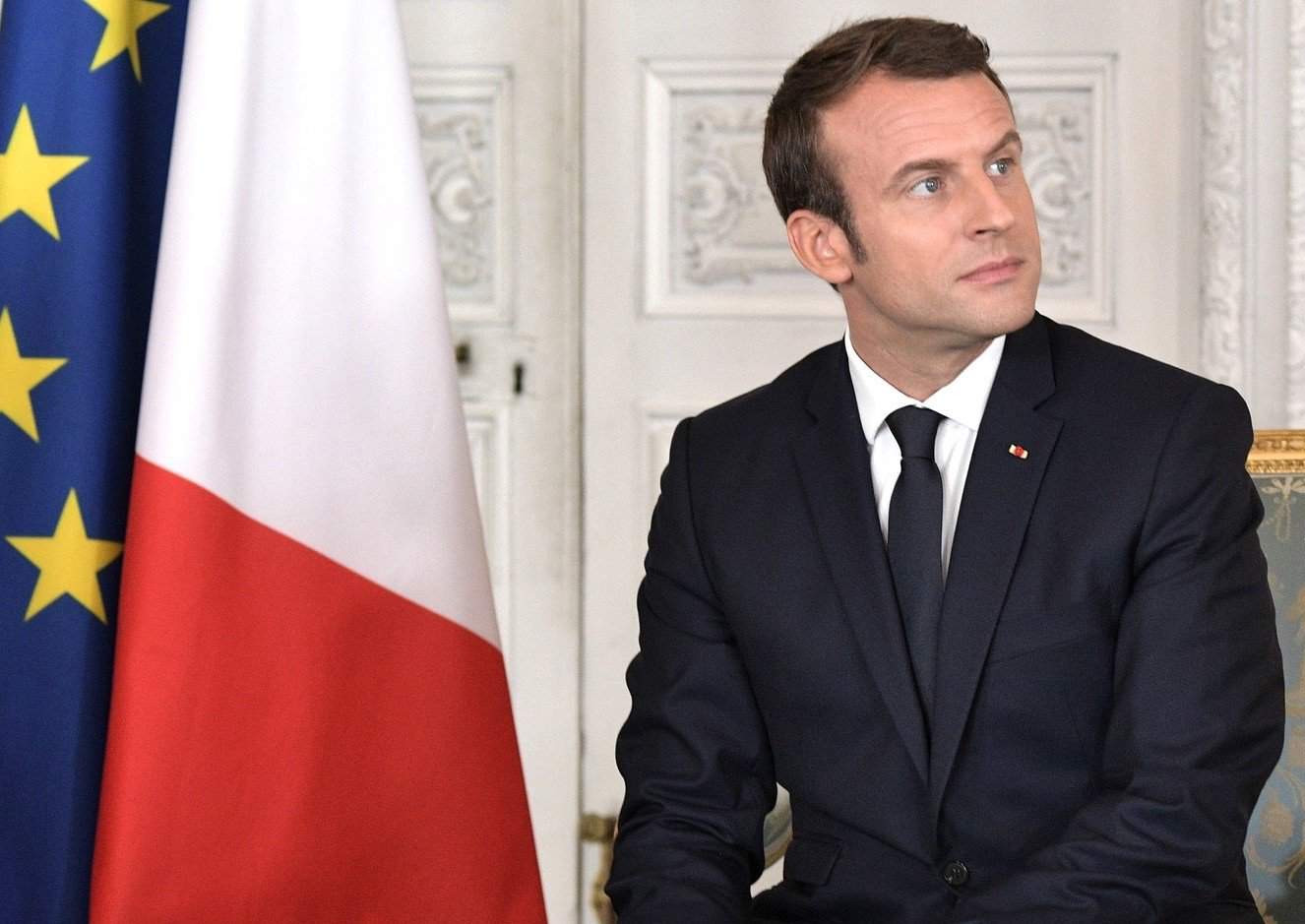

It has been a dramatic year for French unions. On September 22, 2017 President Emmanuel Macron overhauled his country’s labor law by executive order. This was a major milestone for the young politician who had pledged to turn France into a “nation that thinks and moves like a startup.”

Macron has spent much of his political career fighting to liberalize his country’s labor law. While serving as Minister of Economy, Industry and Digital Affairs for President Francois Hollande, he supported a law that would have, among other pro-business reforms, reduced the minimum overtime pay for employees who worked beyond the (otherwise mostly symbolic) 35 hour work week. He has repeatedly warned that France’s strong workplace protections make it unattractive for investors. This argument resonates in a country suffering from chronically high unemployment. France’s unemployment rate of 9.5% is roughly double that of the United Kingdom or United States.

Notwithstanding France’s reputation for worker-friendly labor law, it has one of the lowest union membership rates in the developed world. Only 8% of its workforce is unionized, and this number drops to a mere 5% in the private sector. This is the lowest union density in the European Union, and is even lower than in the United States. Because unions are not able to rely on the power of mass membership, they are heavily dependent on the statutory protections found in France’s extensive labor code, the Code du Travail. These protections are far more generous than those found in the NLRA. French unions are not mere vehicles for collective bargaining. They participate in almost every aspect of the employment relationship, even in workplaces which are not themselves unionized.

The secret to this power lies in the structure of French labor law. In the United States, unions negotiate with individual employers and create contracts that bind an individual firm. In France, on the other hand, unions engage in sector-wide or industry-level bargaining. Representatives of the five major unions sit down with the largest employers and create rules that bind all businesses in that sector of the economy. Hundreds of these agreements are negotiated or extended every year. This means that, despite the low rate of actual union membership, the overwhelming majority (up to 98%) of French workers are covered by union-negotiated collective bargaining agreements. In a very real way, French unions are the representatives of all workers in the country, and not just of their members.

This is the relationship which Macron seeks to change. One of the central elements of the new labor law allows small employers (defined as businesses with fewer than 50 employees) to negotiate changes in employment conditions without a union representative present. This allows individual firms to negotiate for workplace rules which are less worker-protective than the industry standard. This change is defended as a means to improve flexibility, but it will also weaken workers’ bargaining position by allowing employers to negotiate from a position of power. It will also likely undermine the solidarity that those workers currently feel with the national unions. Existing law makes it clear that their work conditions are determined by the national labor movement. If conditions are instead set at the firm-level, this solidarity could disappear.

Other elements of worker power are also endangered by Macron’s executive order. Previously, French labor law required the creation of several representative institutions at the workplace. These included works councils and health and safety committees. Macron’s executive order abolishes these institutions and replaces them with a “single common representative body.” The effects of this change are hard to predict, but it will reduce the number of paths open for submitting an employee grievance.

Macron’s executive order targets employment law as well as labor law. Unlike the United States, French employment law presumes that an employee can only be fired for cause. The definition of good cause is fairly broad, however, and employers have always been able to lay off workers if it was a business necessity. Macron’s reforms expand the definition of business necessity and limit the fines that an employer faces for an unjust discharge. For instance, an employer who wrongfully fires an employee who has worked for two years will now be liable for no more than three months lost wages. The order also reduces the time in which employees can bring a wrongful termination suit from 24 months to 12 months.

While Macron’s collective bargaining reforms target small enterprises, some of these employment law changes benefit only the largest corporations. Business necessity, for instance, was historically determined on a global basis. A company could not claim that its business needs required it to lay off workers in France while opening up new factories in another country. Macron’s reform only requires that the business face problems in France. This change grants increased flexibility to multinational corporations while offering nothing new to small domestic businesses. While Macron justified his reforms by citing high unemployment, this seems to have encouraged increased firing rather than increased hiring. Companies like Peugeot have laid off thousands of workers despite increased profits, something which would have been illegal under the pre-Macron laws.

The unions’ response to these changes was fairly muted at first. The most radical French union, the CGT, called for massive protests against the law, but none of the other four major unions were willing to join them. This weak response may have been rooted in the fact that Macron had campaigned heavily on liberalizing the labor market. The reforms could therefore be presented as reflecting an electoral mandate. Some union leaders believed that resisting them would be a waste of political capital. France’s largest union, the CFDT, seemed to worry that strongly opposing the reforms would weaken its relationship with the administration and reduce its leverage in future negotiations.

This reluctance collapsed when the administration began liberalizing sectors which had gone unmentioned during the campaign. France’s public railway system, the National Society of French Railroads (SNCF), had played no role in the 2017 election. It is also a powerful center of entrenched labor power. SNCF employs 140,000 workers with a special employment status (the Statut des Cheminots) which gives them significantly better working conditions than many other employees. They cannot be fired for business necessity reasons and are able to retire in their mid-50s (although their salaries remain close to the national average). In March of this year, Macron’s prime minister Edouard Philippe unveiled a plan to convert the SNCF into a public limited corporation, rescind the Statut, and close unprofitable railway lines. The response was dramatic, with large numbers of railway workers walking off the job.

This signaled the beginning of a vast new wave of strikes which is still ongoing. A civil servant strike began on March 22, while student protests broke out at universities across the country. Major strikes also broke out at Air France and in the country’s energy sector. Job cuts at the supermarket Carrefour, Europe’s largest retail employer, had already brought workers out on strike in February, but their cause now merged into the larger national protests. This all represents France’s largest strike wave in years, and demonstrates the continued power of France’s labor movement. This labor radicalism may also have received a boost from a well-timed historical anniversary. It is currently the fiftieth anniversary of the May 1968 protests that helped bring down Charles de Gaulle. Macron has been notably hesitant to commemorate that anniversary.

Yet it remains unclear how long the strikers will be able to maintain their momentum. Public opinion may be turning against them. One poll showed 69% support for eliminating the Statut, while another poll shows only 43% support for the railway strike. While 143,000 people participated in pro-labor protests this May Day, the French labor movement is facing an uncertain future.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 15

The Department of Labor announces new guidance around Occupational Safety and Health Administration penalty and debt collection procedures; a Cornell University graduate student challenges graduate student employee-status under the National Labor Relations Act; the Supreme Court clears the way for the Trump administration to move forward with a significant staff reduction at the Department of Education.

July 14

More circuits weigh in on two-step certification; Uber challengers Seattle deactivation ordinance.

July 13

APWU and USPS ratify a new contract, ICE barred from racial profiling in Los Angeles, and the fight continues over the dismantling of NIOSH

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

the Supreme Court allows Trump to proceed with mass firings; Secretary of Agriculture suggests Medicaid recipients replace deported migrant farmworkers; DHS ends TPS for Nicaragua and Honduras