Peter Morgan is a student at Harvard Law School.

What’s the union button of the digital age? Buttons in the usual sense are hardly obsolete, as the Board in its recent Tesla decision made clear. And as long as people come to work together, see each other, and abide by company uniform policies, labor law will always have to clarify the role such “union insignia” must have in the workplace. (It has, in a very long history, in cases like Republic Aviation.) But the Board has yet to really address how these principles should apply in digital work contexts. Is there such a thing as “digital insignia”? Is it just covered by the same rules? On these questions, we really only have silence — probably to our detriment.

At the end of August, the National Labor Relations Board found employer restrictions on displays of union insignia — “such as buttons, pins, and stickers” — presumptively invalid. Per the decision, Tesla, Inc., the Board would require employers to show “special circumstances” if any such restriction were to stay within the law. And to the uniform policy in question — Tesla black shirts, with only the company logo visible — the Board expressed skepticism. It was not enough to allow employees the chance to talk about their union, it was also “critical” that they be able to wear it.

At first glance, this ruling would seem to have little bearing on more digital work. The setting, for all the Silicon Valley branding, is still more manufacturing than Microsoft. But the opinion opens the fight for digital organizing on two fronts. For one, it signaled its willingness to return to a more forgiving standard for employee use of employer-owned email channels: “We would be open,” it wrote, “to reconsidering Caesars,” a Trump Board decision allowing companies to prohibit union-related solicitations through company email systems.

Second, it ultimately centered a very physical and time-tested vision of union insignia. To be fair, the Tesla policy in question was about just that kind of insignia, and in reaching its holding, the Board likely found some help in resorting to long-existing caselaw on the subject. But for all of this opinion’s openness to digital communication through e-mail (or potentially, through other applications), the opinion still remains remarkably grounded in the physical world of the in-person workplace. Insignia, the opinion describes, are things that you don on your body. They’re always shirts, buttons, stickers in the traditional sense, but that can come with the same traditional limitations.

What’s the Board missing here? Some reference to the variety of insignia that are not just physical. Insignia, unlike the kind of direct communication the Board’s email cases have handled, do something simple in all their iterations: they display an image — often a text or with text — while attached to an identifiable person or thing. “I voted” stickers, union strong pins, laptop decals — all of these do this basic act, and they do it to say something about the wearer. They communicate something, but they do it outside of the immediate words of a conversation, as part of environment but still from a personal source.

In the digital context, we still have plenty of places for us to display our positions. When you don’t have a full, video-game-like avatar, you usually have, depending on the platform, at least a profile picture, which is your visual face; your username, which is your traveling nametag; and some kind of profile biography. When you post or participate in an online platform, these features will follow your activity.

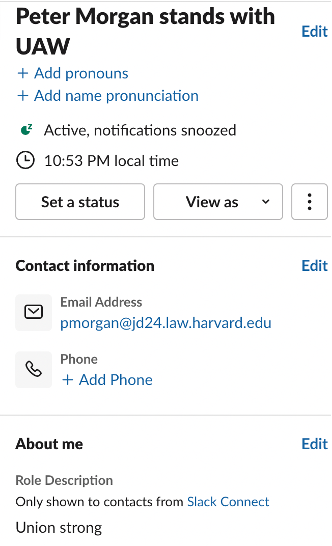

To make this a little more concrete, let’s take Slack, a popular professional organizational and messaging application. Here is my profile as it appears by default — with my name, a solid color profile picture (top), and nothing in my “About me” section.

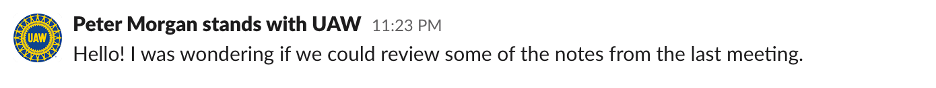

Here is what it could look like during an organizing campaign or strike. It says something now, sure, but the way insignia do — by being on my digital “person” on Slack. In the same sense, it does not “communicate” in the same directed way that talking to or emailing a co-worker does. But in so far as Slack has given me any ways for me to be identified among other users, it has also given me a chance to express support for a labor organization.

Having a professional digital presence thus adds a new front for organizing, one with its own set of complications. Should the profile picture be a more permissive for holding/being insignia than usernames or profile biographies? Should the Board mark a practical distinction between platforms owned by the employer and those it licenses? Email and messaging applications like Slack or Microsoft Teams?

Even if the Board did include these digital forms in the description of insignia, it would remain unclear as to when they would be acceptably constrained. The Tesla decision allows for a “special circumstances” test that can allow prohibitions on union insignia in many public-facing settings. In one case cited, the Board notes that one justification an employer could use would be sustaining a “Wonderland ambience that the employer sought to create through a ‘trendy, distinct, and chic look’ for its employees” (W. San Diego). For email “insignia,” this could prove particularly problematic and ambiguous; while you may email your colleagues, you are just as — if not more — frequently emailing customers, vendors, and other people outside the firm.

The Board’s omission on this front is unfortunate, not only in excluding a kind of union activity from its explicit protection but also an increasingly important one. Nearly 18% of people worked from home last year, triple the amount from before the pandemic. And even many office workers rely increasingly not just on email but additional applications like Slack.

Increasingly, digital platforms have become an increasing hotbed of union busting, especially in the tech industry. That the Board will face charges on digital communications is certain (including, for instance, in the case of Activision Blizzard). But with communications such as avatar and profile appearance remaining in ambiguity, union organizers may need to either exercise more caution or demand clarity in future proceedings.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

the Supreme Court allows Trump to proceed with mass firings; Secretary of Agriculture suggests Medicaid recipients replace deported migrant farmworkers; DHS ends TPS for Nicaragua and Honduras

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.