Jasmine Loo is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

The devastating impact of the COVID-19 pandemic has had a heavy toll on the healthcare workers of America. From having to deny patients a bed due to a shortage of resources, being abused and harassed for advocating vaccines, being unable to talk to and reassure patients due to having to care for twice the usual number of patients, helping critically-ill patients say final goodbyes to their families over phone, and having to volunteer to load bodies at the morgue, healthcare workers have been placed in innumerous impossible situations since the pandemic reached the United States in January 2020.

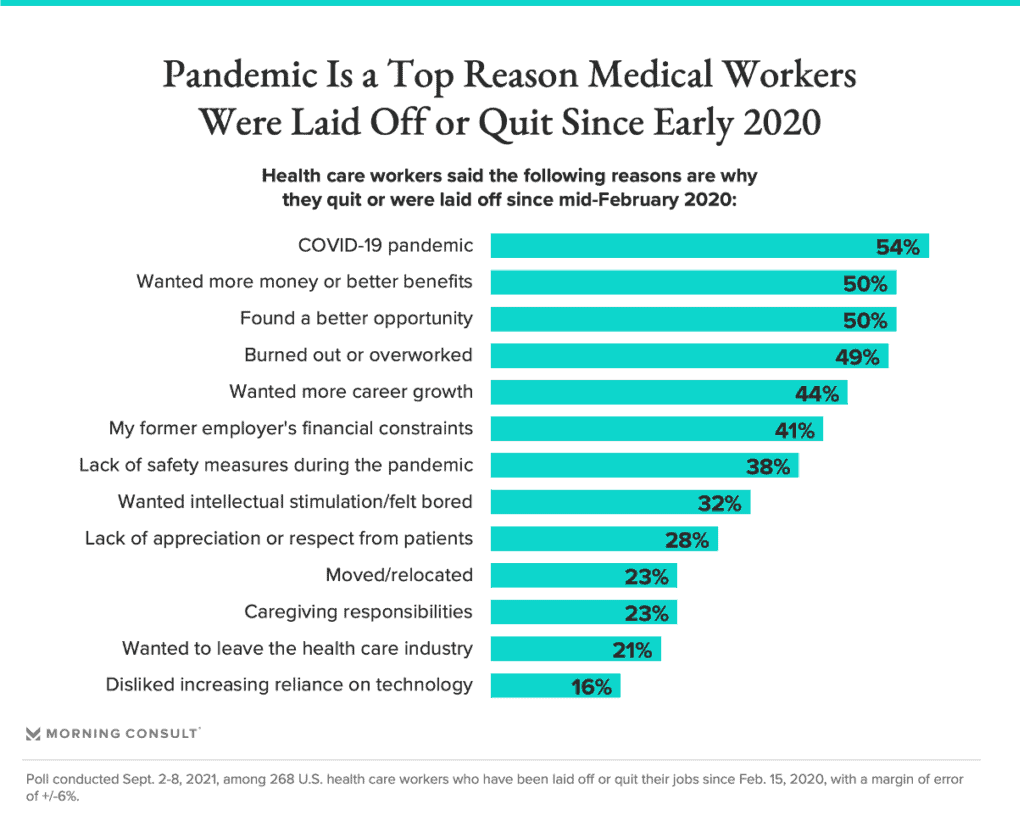

The impact is overwhelming. According to a Morning Consult survey, 18% of surveyed healthcare professionals have left their jobs, citing exhaustion, financial reasons and most of all, the COVID-19 pandemic, with labor shortages impacting the workplaces of 79% of medical workers. Smaller practices are also struggling financially as patients avoid visiting their primary care physicians due to fear of the virus, which has “accelerate[d] the closure of the smaller practices”.

Due to the stressful and unpredictable nature of and ethical issues associated with healthcare, medical professionals were already at an increased risk of mental health issues, with estimates suggesting that 16% to 22% of University of Colorado Hospital nurses experience anxiety, depression or post-traumatic stress disorder (PTSD) and 54.4% of US physicians surveyed by Mayo Clinic experience burnout, despite their inherently higher resilience. Women, African American and Latino workers, along with allied health professionals like social workers, experienced even more stress.

The reasons for high attrition are the systemic undervaluation of labor and understaffing in medical institutions. While pay varies drastically across different sectors of the healthcare industry, some workers, such as nursing home staff, are “not even making a living wage”, with certified nursing assistants earning a median pay of $14.82 in 2020, with the lowest 10% earning $10.70 per hour, what one nursing-home aide describes as “competing literally with McDonald’s for wages.” A single nursing-home aide may be responsible for 16 to 18 patients on her own, given that understaffing was already a chronic issue pre-pandemic. Punishing long hours, such as multiple days of consecutive 12-hour shifts, or single shifts lasting 28 hours four times a month, are not uncommon. Even where workers have rest or meal breaks, time constraints and the urgency of an incoming ICU case might compel some of them to work through their break without it be considered as compensable working time. As one registered nurse remarked, “If it’s a very busy night, I don’t get my breaks at all. I don’t eat or drink [for] 10 hours.”

The exodus of nurses particularly affects rural hospitals with fewer resources, as staff left for states like New York and California due to the high bonuses and hazard pay they were offering, further aggravating the unequal distribution of healthcare staff across the U.S. and disadvantaging vulnerable populations already lacking access to healthcare and resources.

The pandemic also uncovered an absence of safety measures for healthcare workers. Despite calls for hospitals and clinics to develop protocols to protect workers echoing throughout workplace safety advocates and unions in March 2020, the House’s Healthcare Worker Protection Act, which would have mandated emergency safety standards for healthcare workers and required the provision of PPE and safe distancing measures, failed. It was never put to a vote after lobbying from the American Hospital Association. Only in June 2021 did the U.S. Department of Labor issue emergency standards specific to the healthcare sector, such as mandating the use of PPE, physical distancing, regular disinfection and ventilation, which previously was left to the discretion of healthcare employers.

Unionization alleviates these problems to an extent. For example, data from the National Sample Survey of Registered Nurses shows that unionized registered nurses have a 15% higher wage than non-union workers. The unionization of healthcare workers increases assertion and enforcement of workplace safety regulations, lowers COVID-19 mortality rates, improves access to PPE and increases the quality of infection control mechanisms. Unions also protect against discrimination and thus unionized employees suffer less discrimination based on their race or immigration status than do their non-union peers.

However, given that government population data indicates only 17% of nurses and 12% of other U.S. health workers are unionized, these systemic problems with healthcare remain prevalent in the overstretched healthcare market. The ultimate victims are the healthcare workers, who sacrifice their health, time and personal lives, and suffer from moral injuries (characterized by “intense feelings of guilt, shame or disgust”) when they find themselves unable to provide adequate care and blame themselves for it. An ICU nurse described her experience of denying a visitor access to her dying mother on Mother’s Day as “I upheld the rule on the piece of paper. But in terms of what would a good person do? It’s not that. … Am I really a good person? There’s that seed of doubt.”

Despite unique restrictions on their right to strike, in the past year, healthcare workers have conducted strikes in New York, Washington, Chicago and Maryland over PPE provision, working conditions, and unsustainable work hours, but little progress has been made. While Chicago nursing home workers were able to negotiate an average raise of $2, improve pandemic hazard pay, sick days and guarantees of PPE provision, and New York’s governor Kathy Hochul intervened to negotiate better wages and benefits to hold off a strike in New York’s nursing homes, other strikes in Washington and Maryland have received no response.

Looking to the future, academics David Myles and Duncan Maru suggest that a combination of soft and hard measures should be implemented. Soft measures include encouraging peer support and expanding mental and physical healthcare access. Hard measures include legislative action to lighten workloads and improve staffing ratios, such as New York’s “safe hospital staffing” bill (A108B/S1168A), which establishes clinical staffing committees comprised of 50% frontline staff, who participate in determining safe, transparent and independent nurse-patient ratios. Enforcement agencies should also rigorously enforce safe workplace rights and compensation, such as by protecting hospital staff from retaliation for speaking out about staffing shortages.

Most of all, the legislature should fortify the rights of collective organization of healthcare workers. Alternatively, regulators could set up wage boards and commissions to establish basic working standards and fair compensation. In areas where unions are stepping up to campaign forcefully, they are winning paid sick leave and hazard pay, and setting industry standards that benefit all workers, triggering a wave of interest in unionization.

Overall, collective bargaining may offer the best route to improving the healthcare industry substantively. Healthcare workers deserve to be safe, valued and compensated fairly for the essential work they do.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.

July 1

In today’s news and commentary, the Department of Labor proposes to roll back minimum wage and overtime protections for home care workers, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit by public defenders over a union’s Gaza statements, and Philadelphia’s largest municipal union is on strike for first time in nearly 40 years. On Monday, the U.S. […]

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]