Zachary Sorenson is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

For years, Amazon promised its Fresh and Prime Now gig delivery drivers they would receive all customer tips. Instead, Amazon diverted these tips to cover base wages, according to a complaint against Amazon by the Federal Trade Commission (FTC) last month. The FTC’s settlement with Amazon is a win for the drivers who will now be repaid their diverted tips. But it also raises questions about what role a consumer-focused agency can—and should—play in protecting gig workers moving forward.

Amazon Flex: deceiving workers and customers

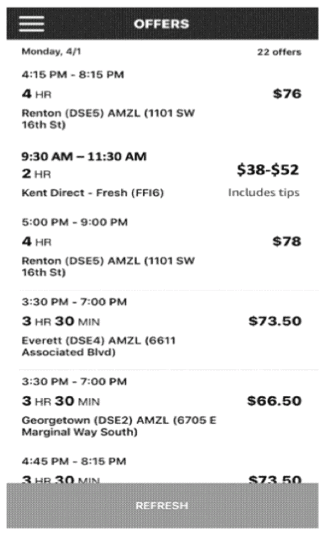

When Amazon launched the gig delivery platform Flex in 2015, it told drivers they would be paid $18-25 per hour and would “receive 100% of the tips [they] earn.” At first, Amazon delivered on that promise. The Flex app presented drivers (classified by Amazon as independent contractors who used their own vehicles) with a list of “delivery blocks” to choose from, each with a guaranteed minimum payment. When drivers earned tips, Amazon paid drivers the full amount and listed them separately from the base payment.

In 2016, however, Amazon started cutting costs. Without telling drivers, it started using average tip data to lower its base rates, diverting tips to meet the $18-25 threshold. For example, if Amazon predicted $6/hour in tips, it might have promised an $18/hour payment to drivers but set an internal base rate of $12/hour and only made up the difference if necessary. At the same time, it stopped showing drivers their earnings and tips separately.

This entire time, Amazon continued telling both drivers and customers that drivers would receive all tips—representations that may have been technically true but were deeply misleading. Amazon was not the only company to divert customer tips to cover base pay in this way—Instacart and DoorDash were widely criticized for similar behavior—but Amazon distinguished itself by the deceptive and evasive ways it represented its practices to both drivers and customers.

Amazon diverted tips for several years until it learned it was being investigated by the FTC.

In February, the Commission voted unanimously to settle with Amazon, requiring the company to reimburse drivers for over $60 million in diverted tips. This amount is unusually high for a settlement, as former FTC Bureau of Competition Director Jessica Rich explained, since many companies negotiate to pay less than the total damages. Still, as one Flex driver noted, even full reimbursement cannot make up for all losses drivers suffered: “If Amazon is able to get away with just repaying what they took, then it is the same as awarding them an interest-free loan… meanwhile, I still have the debt from several years ago which has compounded at a nearly 30% interest rate.”

$60 million was probably the maximum the FTC could obtain, however, because of the limits inherent to an agency structured as a reactive enforcer rather than a proactive regulator. Currently, the FTC can only assess penalties when a company violates an existing order; first-time enforcement is limited to judicially ordered restitution, which effectively sets an upper limit on settlements as well.

Can a consumer-focused agency protect gig workers?

The FTC has a dual mission to promote competition and protect consumers. Unsurprisingly, its consumer protection authority under Section 5 of the FTC Act, which prohibits “unfair or deceptive acts or practices in or affecting commerce,” is defined in terms of “injury to consumers.” And although some scholars have pushed back, its antitrust enforcement has historically used consumer welfare as the yardstick for evaluating competition as well.

Because the FTC issued the Amazon complaint under its consumer protection authority, it focused on Amazon’s deception of customers, even though drivers were the primary victims. Republican Commissioner Noah Joshua Phillips and Acting Chairwoman Rebecca Kelly Slaughter, a Democrat, called Amazon’s behavior “outrageous.” They argued the FTC should do more to ensure that gig platforms treat workers “fairly and non-deceptively.” But how well can standards designed for consumers be extended to workers, and what happens when platforms deceive workers in ways that do not provide a consumer harm hook for FTC enforcement?

In one sense, protecting gig workers from the sort of unfair and deceptive practices business use against consumers is a natural expansion for the FTC’s role. On one view, the structure of many gig platforms essentially makes workers “consumers” of gigs, selecting from a range of differently priced options based on asymmetrical information provided and controlled by the platform. Worker-platform relationships are comprised of an aggregate of discrete individual transactions rather than ongoing mutual commitments. The Amazon Flex app even lets drivers “shop” for gigs in a way familiar to anyone who has used its consumer site.

However, whether the current gig economy does make workers analogous to consumers is a separate question from whether it should. Legislatures and voters around the country are grappling with this issue, and with how gig workers should fit into the employee-contractor dichotomy that predates the rise of atomized work intermediated by large internet platforms.

In the Amazon case, a majority of the Commissioners recognize this broader debate but argue it shouldn’t prevent the FTC from doing more to protect gig workers as analogs to consumers in the meantime—they only disagree about how to do it and whether the FTC already has the requisite authority.

Commissioners Phillips and Slaughter disagree whether the gig economy is a net benefit or harm to workers, but they do agree platforms “must treat their workers fairly and non-deceptively, just as they must consumers,” and that the FTC should act accordingly. However, they argue the FTC lacks sufficient authority to do so. Accordingly, they invite Congress to provide “direct penalty authority to deter deception aimed at workers,” enabling the FTC to deter wrongdoing by assessing penalties without a prior order, as well as rulemaking authority “to address systemic and unfair practices” and create a level playing field up front rather than being limited to case-by-case adjudication only after deception is uncovered.

Commissioner Rohit Chopra wrote separately to argue the FTC can also do more with its existing authorities—both antitrust and consumer protection—to protect gig workers. He argues the FTC should resurrect its “penalty offense” authority to penalize companies who violate any previous cease-and-desist orders, even if they were notthe original target (here, that could mean penalizing companies other than Amazon who attempt similar deceptive tip practices). He also argued the FTC should use its antitrust authority to better “polic[e] markets for anticompetitive conduct that harms workers,” rather than just consumers.

With President Biden poised to nominate tech critics to the FTC and other senior roles and bipartisan interest in Congress in examining consolidated power in the tech industry, including the gig economy, both avenues for greater enforcement on behalf of workers seem possible. Greater enforcement by the FTC against the type of “outrageous” worker deception Amazon got away with for years will help gig workers. But while consumer-type protections for workers are a promising new frontier, they cannot solve the broader challenges posed by the contractor-employee distinction and the need to establish further rights and protections for gig workers beyond being treated fairly and non-deceptively.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.

July 1

In today’s news and commentary, the Department of Labor proposes to roll back minimum wage and overtime protections for home care workers, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit by public defenders over a union’s Gaza statements, and Philadelphia’s largest municipal union is on strike for first time in nearly 40 years. On Monday, the U.S. […]

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]

June 27

Labor's role in Zohran Mamdani's victory; DHS funding amendment aims to expand guest worker programs; COSELL submission deadline rapidly approaching

June 26

A district judge issues a preliminary injunction blocking agencies from implementing Trump’s executive order eliminating collective bargaining for federal workers; workers organize for the reinstatement of two doctors who were put on administrative leave after union activity; and Lamont vetoes unemployment benefits for striking workers.