Sara Tsai is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

From Dance Moms to So You Think You Dance (SYTYCD), Dancing with the Stars, and World of Dance, television programming featuring competitive dance has increased over the past few decades, inspiring many parents to enroll their young kids in local dance classes. As competitive events have grown in size and reach, the world of dance has expanded greatly, with dance studios constituting a $3.8 billion market in 2022. However, recent allegations of rampant abuses by competition judges, choreographers, and instructors raise alarming concerns about the need for better labor protections for dancers.

Structure of Employment in Professional Dance

Today, dance employment is shifting from the company model to freelancing. While dance unions exist, they are often limited to dancers who are employed by a dance company. Therefore, dancers lack bargaining power to advocate for labor protections as independent contractors.

The decentralization of jobs makes current labor laws ill suited for regulating the blurry lines of the dance world, which may seem larger than life on television but is in reality an intimate community. Dancers, instructors, and choreographers often cross paths, and therefore individual reputation is critical for maintaining and securing employment. Within this ecosystem where your dance idol at 8 years old might be your competition judge at 15, your employer at 19, and your tour supervising choreographer at 21, the line between employer and employee, supervisor and assistant, mentor and mentee, and teacher and student can be unclear.

Recent allegations against the prominent dance company Break the Floor Productions, which has a reach of over 300,000 dancers annually, demonstrates this. Eight former staffers and students detailed alleged inappropriate sexual propositions by various members of the company. One complainant, Myles Lavallee, had caught the attention of the Emmy Award–winning choreographer Travis Wall at a dance competition where Wall judged him, and at 16, Lavallee attended a party where Wall allegedly gave him crystal meth. After a few texts and calls, Lavallee agreed to be Wall’s dance assistant and was thereafter flown around the country to help Wall teach choreography. Wall allegedly pursued a sexual relationship with Lavallee, who turned him down, and subsequently cut off communication with Lavallee without warning.

How Can Labor Law Better Protect Dancers?

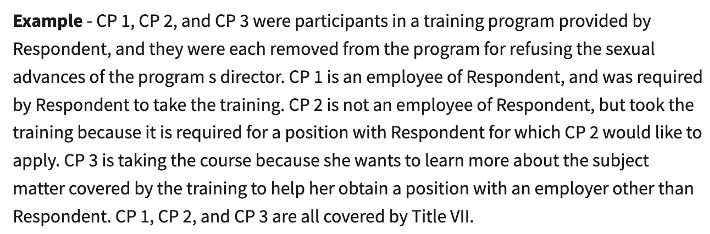

One possible avenue for tackling these blurry lines is to expand protections of dancers as job applicants and trainees. Under U.S. Equal Employment Opportunity Commission (EEOC) guidelines, entities may not discriminate in apprenticeship or other training programs, “regardless of whether the program is the product of an employment relationship,” and may consider discrimination in training programs as discrimination in hiring if “participation in the program regularly leads to employment.” Here is the textbook example given by the EEOC (note: CP stands for “charging party”):

Here, CP 3 could be interpreted to include participants in dance competitions, where dancers often seek to work for the faculty and judges, and agencies and companies scout out talent. For example, The Dance Awards (TDA), which is run by Break the Floor, is one of the country’s largest and most prestigious dance competitions. Many TDA alumni have gone on to television shows like America’s Got Talent, Dance Moms, Dancing with the Stars, and SYTYCD; movies like Steven Spielberg’s West Side Story; and shows like the Radio City Rockettes’ Christmas Spectacular. TDA is more than a competition; it also acts as a training program and an industry gateway. Competitors are required to register for the TDA workshop, which professional dancers, who are not part of the competition, are also allowed to register for. The workshop offers “over 14 hours of classes from America’s top dance educators” and opportunities like “acting classes, casting auditions, agency auditions and more.” Among the renowned faculty members is the aforementioned Travis Wall.

Wall is one example of how interconnected the dance ecosystem is and how much power and control an employer can have even before the employment relationship formally starts. Past winners and runner-ups of TDA include singer-songwriter Tate McRae, who had won in 2018 with a Wall-choreographed solo; Dance Moms star Maddie Ziegler, who had performed with Wall on SYTYCD; and SYTYCD All-Stars Lex Ishimoto and Taylor Sieve, who are now members of the Wall-founded Shaping Sound company and on the faculty for several Break the Floor competitions. This shows how competition participants can fall into the CP 3 profile; in Ishimoto and Sieve’s case, they not only obtained positions with an employer other than Break the Floor (Wall’s Shaping Sound Company), but also were hired by Break the Floor subsidiaries as faculty members.

An EEOC investigation should be conducted regarding the harassment, particularly sexual harassment, claims of dancers competing or working at competitions such as those hosted by Break the Floor. EEOC guidelines state that employers can be liable for harassment by non-supervisory employees or non-employees over whom they have control. Therefore, even if the perpetrators working for Break the Floor are considered independent contractors, the company could still be liable. While many of those impacted by the harassment, particularly young children, appear to be customers rather than workers, the allegations brought by those like Lavallee and the career trajectories of Ishimoto and Sieve show how the blurry lines of dance employment can fit within existing labor law frameworks for job applicants and trainees.

Potential Barriers to Progress: Time & Culture

One major roadblock, however, is the EEOC time limit for filing a charge, which is 180 days. The employment relationship — and therefore timeframe of discrimination, harassment, and abuse — can span years, from a dancer’s childhood and teenage years to their adult career. Therefore, this time limit may render dancers’ claims null. Additionally, the lifespan of a dancer’s performance career is short, ending around the age of 35 often due to the physical demands of the job. The duration of litigation, coupled with impact on individual reputation, may be too costly for dancers to seek legal recourse.

What the allegations against Break the Floor Productions revealed is part of a larger trend of predation, exploitation, and abuse in the dance ecosystem. Last year, a pair of professional dancers sued dance instructor Mitchell Taylor Button for claims of sexual and verbal abuse and assault, starting as early as when one plaintiff was 13 years old. Just a few months ago, 56 former students at the prestigious University of North Carolina School of Arts accused faculty of a range of abusive misconduct, including rape, that spanned a period of over 40 years. 120 current and former students of Rider University’s Theater and Dance Department submitted complaints of sexual harassment, racism, and body shaming by current and former faculty.

There are no easy answers to the problematic culture of abuse and exploitation in the dance world, but the recent lawsuits and complaints provide hope that more people will step forward and dancers can collectively organize to pursue justice. The power in numbers may alleviate the concerns of retaliation and potentially offer anonymity to those who are scared to file individual claims. It is the dance industry’s time of reckoning as to whether it will value dancers as more than just replaceable, glitzy commodities, and create a culture where young kids training in local studios can look forward to safe and meaningful careers as performers.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

January 29

Texas pauses H-1B hiring; NLRB General Counsel announces new procedures and priorities; Fourth Circuit rejects a teacher's challenge to pronoun policies.

January 28

Over 15,000 New York City nurses continue to strike with support from Mayor Mamdani; a judge grants a preliminary injunction that prevents DHS from ending family reunification parole programs for thousands of family members of U.S. citizens and green-card holders; and decisions in SDNY address whether employees may receive accommodations for telework due to potential exposure to COVID-19 when essential functions cannot be completed at home.

January 27

NYC's new delivery-app tipping law takes effect; 31,000 Kaiser Permanente nurses and healthcare workers go on strike; the NJ Appellate Division revives Atlantic City casino workers’ lawsuit challenging the state’s casino smoking exemption.

January 26

Unions mourn Alex Pretti, EEOC concentrates power, courts decide reach of EFAA.

January 25

Uber and Lyft face class actions against “women preference” matching, Virginia home healthcare workers push for a collective bargaining bill, and the NLRB launches a new intake protocol.

January 22

Hyundai’s labor union warns against the introduction of humanoid robots; Oregon and California trades unions take different paths to advocate for union jobs.