Desirée LeClercq is the Proskauer Employment and Labor Law Assistant Professor at Cornell University's School of Industrial and Labor Relations in Ithaca, New York, where she teaches international labor law, U.S. labor law, and employment law.

An effective anti-union strategy, management has learned, is to fire would-be organizers before they have the chance to generate solidarity and mobilize their co-workers. Employers seeking to remove union organizers point to company policies like civility rules and allege that violations of those rules, not the workers’ organizing efforts, resulted in dismissal. Starbucks’ infamous “Barista Approach,” for example, requires workers to create a “warm and friendly environment” and display “a positive attitude” while crafting and serving products. In 2022, Amazon made headlines when it fired workers protesting its COVID-19 policies because, management asserted, the protest conduct was a “vile, offensive, and disparaging verbal attack … that no employer ever would—or should—tolerate or accept in a civilized workplace.”

The Trump administration’s National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) offered employers significant leeway to fire shop floor organizers accordingly. It overturned longstanding labor doctrine that had viewed workplace civility rules skeptically. It disagreed that organizers need protected space to generate solidarity and show their co-workers that management is vulnerable to contestation.

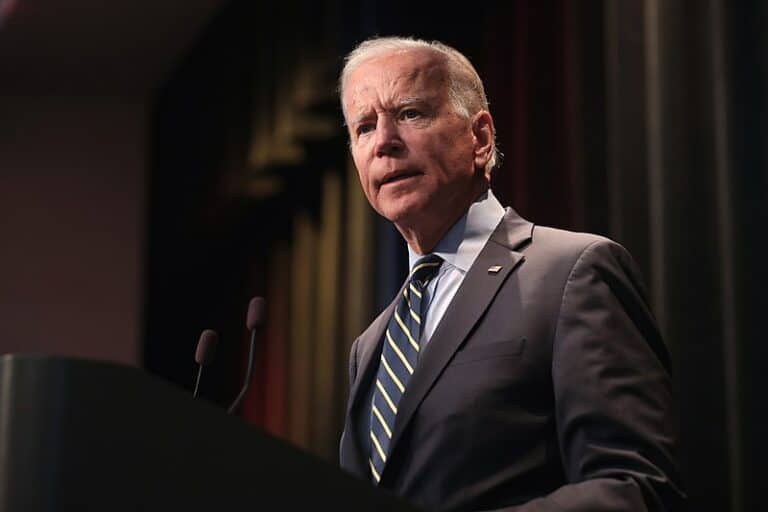

On August 2, the Biden administration seemed to take a significant step to revive those protections. In Stericycle, Inc., the Biden NLRB reversed the Trump Board and held that civility rules have a “chilling effect” on workers by scaring them out of attempting to disrupt the workplace through solidarity and union organizing. Citing “the economic dependency of employees on their employers,” the Biden Board pointed out that “employees are typically (and understandably) anxious to avoid discharge or discipline” and are consequently likely to interpret civility rules to prohibit their statutory right to “form, join or assist labor organizations…”.

Up to this point in the decision, the Biden Board has it exactly right. Workers are anxious. The avalanche of Starbucks and Amazon cases percolating through the NLRB and federal courts exposes a litany of instances in which managers fire workers trying to organize a union. They do so citing workplace conduct rules.

Unfortunately for workers, the Biden NLRB did not stop there.

Rather than reinstate the legal standard that pre-existed the Trump Board called “Lutheran Heritage,” the Biden Board imposed a standard that “builds on and revises” it. And it is here that the Board goes astray. It notes that the Lutheran Heritage standard only “implicitly allowed the Board to evaluate employer interests when considering whether a particular rule was unlawfully overbroad, the standard itself did not clearly address how employer interests factored into the Board’s analysis.” Seemingly sympathetic to those interests, the Biden Board’s new standard “makes explicit that an employer can rebut the presumption that a rule is unlawful by proving that it advances legitimate and substantial business interests that cannot be achieved by a more narrowly tailored rule.”

If Starbucks and Amazon have taught us anything, it is that employers have a deep well of business interests from which to draw to justify firing would-be organizers. In today’s service industry, what business does not have a “legitimate and substantial business interest” in ridding the shop floor of antagonistic workers? Especially when customers made uncomfortable by worker antagonism might simply cross the street to a competitor?

Is it possible to organize a workplace without making customers uncomfortable and, thus, arming businesses with a “legitimate and substantial interest” to fire organizers? Whether we are talking about civil rights, women’s rights, LGBQT+, or labor rights, we are discussing social movements. Those movements have no obligation to be civil. They are not friendly, accepting, or sympathetic to the powerful majority. They are a site of resistance, organization, and solidarity among a powerless minority fed up with the status quo. And while there are obvious limits on how far women and men can go in expressing their solidarity (violence, repetitive abuse, protesting conditions outside the majority’s control come to mind), we as a society must offer them a safe, legal space to express their opposition to build their power.

The Biden administration’s NLRB has identified a series of cases it intends to overturn like this one. Its concession to employer’s interests may be an attempt on its part to protect its legal standards against flip-flopping in future administrations. While understandable, the Board’s new threshold in Stericycle, Inc does not cure the chilling effect on anxious workers. It reinforces the message that workers must keep in line.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 11

Regional director orders election without Board quorum; 9th Circuit pauses injunction on Executive Order; Driverless car legislation in Massachusetts

July 10

Wisconsin Supreme Court holds UW Health nurses are not covered by Wisconsin’s Labor Peace Act; a district judge denies the request to stay an injunction pending appeal; the NFLPA appeals an arbitration decision.

July 9

In Today’s News and Commentary, the Supreme Court green-lights mass firings of federal workers, the Agricultural Secretary suggests Medicaid recipients can replace deported farm workers, and DHS ends Temporary Protected Status for Hondurans and Nicaraguans. In an 8-1 emergency docket decision released yesterday afternoon, the Supreme Court lifted an injunction by U.S. District Judge Susan […]

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.