Cynthia Estlund is the Crystal Eastman Professor of Law at the New York University School of Law.

This is part two of a three-part series. See part one here.

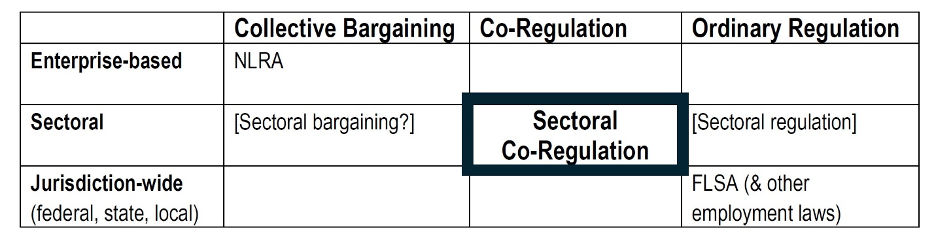

Within any given jurisdiction, legal strategies for raising labor standards (above what market forces and individual contracting might yield) can be located along two axes: A horizontal axis represents divergent modes of setting labor standards, from collective bargaining—in which government facilitates bargaining does not dictate substantive standards—to direct government imposition of minimum standards and rights. A vertical axis represents the level at which standards apply, and runs from jurisdiction-wide standards—national, state, or local—to standards set at the enterprise level.

The conventional US approaches to raising labor standards are located at the opposite corners of the resulting grid: jurisdiction-wide minimum standards and collective bargaining at the enterprise level. One finds no viable alternatives at the opposite two corners of the grid—that is, government-dictated labor standards at the enterprise level or jurisdiction-wide collectively bargained standards. But the range of alternatives expands once we recognize intermediate points on each axis. Sectoral standards fall at the mid-point of the vertical axis, and could be set either by collective bargaining or by regulation. At the mid-point of the horizontal axis lie less familiar hybrid or “co-regulatory” strategies that engage workers’ representatives directly in establishing and enforcing publicly-imposed labor standards.

The New York and California labor standards boards sit at the mid-point of both axes: They set binding public standards at the sectoral level with the participation of representatives of workers and employers alongside public officials. If we compare sectoral co-regulation to its alternatives along both axes identified here, we find that co-regulation has some advantages over both collective bargaining and conventional regulation, and that sectoral standards have advantages over both enterprise-based and jurisdiction-wide standards. Yet sectoral co-regulation is also compatible with both jurisdiction-wide minimum standards and enterprise-based collective bargaining, and might even help to support them.

A. Co-Regulation Versus Bargaining Strategies

The state wage boards and their historical precursors raise labor standards, but they rely not on workers’ collective bargaining leverage—their ability to put economic pressure on employers—but on political and regulatory power. That is important. Our labor laws promised to enable workers to secure better wages and working conditions by organizing and aggregating their bargaining power. Organized labor has long pursued labor law reforms that might make good on that promise. But those reforms, even if enacted, would not address deeper problems of declining labor market power on the part of workers without advanced skills or education. (I argue elsewhere that globalization, deregulation, fissuring, and technological innovations have all tended to sap workers’ bargaining power relative to capital, in part by expanding employers’ ability to replace employees with other workers or technological substitutes.) Workers need to supplement their labor market power, not only to aggregate it. That militates for greater reliance on political power and regulatory strategies for improving work and wages at lower levels of the labor market. Reliance on political power has its risks, of course; but there are many jurisdictions in which solid political majorities support higher labor standards.

An additional advantage of regulatory strategies for raising labor standards lies in the arcane doctrine of federal labor preemption and the uneven geographic distribution of labor’s political power. Labor obviously has greater political support in several “blue” states and cities than at the national level. Yet federal labor law preempts state and local regulation of private sector collective labor relations—including any hypothetical state or municipal scheme of sectoral collective bargaining. By contrast, federal law does not preempt the enactment of higher substantive labor standards at the state or city level. To be sure, states can constrict cities’ lawmaking powers, and some “red states” have preempted progressive reforms in “blue cities.” And preemption doctrine could change in ways that further constrict state lawmaking powers. Still, there is much more room for state and local regulation of substantive labor standards than for state and local regulation of collective bargaining.

B. Co-Regulation Versus Conventional Regulation

Does a shift toward regulatory approaches give up on amplifying workers’ voices in the formulation and enforcement of labor standards? Not necessarily. Co-regulation aims to democratize standard-setting by directly engaging workers and their organizations in the process. Both traditional strategies for setting labor standards have their own democratic bona fides: Collective bargaining democratizes labor standard-setting by giving workers a voice in setting standards at the enterprise level. Legislated minimum labor standards, by contrast, reflect the voice of the public at large, through democratic political processes, in defining decent standards of work. Co-regulation borrows a page from each conception of democracy: It expresses the public’s will, through democratic political channels, to democratize the process of devising and enforcing public labor standards by engaging those whose lives and livelihoods they most directly affect. In so doing, co-regulation taps into workers’ on-the-ground knowledge of conditions and their self-interest in improving and enforcing labor standards.

Federal labor law was supposed to democratize labor standard-setting through collective bargaining. But very few workers today have access to that framework, given the severe challenges of union organizing and of gaining a collective agreement. Even if labor law were reformed to better enable workers to aggregate their bargaining power, many workers just don’t have enough of it to make up the ground they have lost in today’s economy.

C. Sectoral Standards Versus Enterprise- or Jurisdiction-Wide Standards

The case for sectoral standards—versus either jurisdiction-wide or enterprise-level standards—is relatively straightforward. Sectoral labor standards can surmount the least-common-denominator problem with jurisdiction-wide standards; they can be higher than what is feasible across a whole jurisdiction and can address conditions that are distinctive within a sector. Sectoral labor standards, whether set by collective (pattern) bargaining or otherwise, can also address the Achilles’ heel of enterprise-based bargaining by constraining labor-cost-based competition within the sector, and by forcing firms to compete instead through higher productivity, quality, and innovation. Sectoral bargaining over basic labor standards in Europe partly explains both higher union density and the smaller rise in economic inequality in recent decades.

To be sure, sectoral standards still face competition from outside the jurisdiction within which sectoral standards prevail; and they must still take into account productivity within the sector. But sectoral standards, unlike jurisdiction-wide standards, can vary with sector-specific considerations like productivity and the scope of the relevant product market (whether local, regional, national, or transnational). Sectoral standard-setting can be opportunistic in a positive sense. Higher wage floors might be sustainable, for example, in sectors with few competitors (like hospitals in many regions, or Amazon warehouses), or local product markets (like hospitality and fast food), or both.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

March 5

Colorado judge grants AFSCME’s motion to intervene to defend Colorado’s county employee collective bargaining law; Arizona proposes constitutional amendment to ban teachers unions’ use public resources; NLRB unlikely to use rulemaking to overturn precedent.

March 4

The NLRB and Ex-Cell-O; top aides to Labor Secretary resign; attacks on the Federal Mediation and Conciliation Service

March 3

Texas dismantles contracting program for minorities; NextEra settles ERISA lawsuit; Chipotle beats an age discrimination suit.

March 2

Block lays off over 4,000 workers; H-1B fee data is revealed.

March 1

The NLRB officially rescinds the Biden-era standard for determining joint-employer status; the DOL proposes a rule that would rescind the Biden-era standard for determining independent contractor status; and Walmart pays $100 million for deceiving delivery drivers regarding wages and tips.

February 27

The Ninth Circuit allows Trump to dismantle certain government unions based on national security concerns; and the DOL set to focus enforcement on firms with “outsized market power.”