Sharon Block is a Professor of Practice and the Executive Director of the Center for Labor and a Just Economy at Harvard Law School.

Seema Nanda is the former U.S. Solicitor of Labor and a Fellow at the Center for Labor and a Just Economy at Harvard Law School.

Decades of Labor Days have come and gone with no hope of labor law reform legislation moving through the U.S. Congress. Since the Taft-Hartley reforms of the 1940s, few issues have divided the parties more clearly than labor law reform. The last Republican to consider voting for comprehensive labor law reform was Arlen Specter — and then he became a Democrat shortly thereafter. But this Labor Day, the vibe around the potential for labor law reform seems different.

Unexpectedly, both Democrats and Republicans are talking about a reform that would align the U.S. labor law system more closely with that common in Europe and most of the rest of the world. Sectoral bargaining — negotiating wages, benefits, and working conditions across an entire industry or occupation rather than at individual workplaces — is gaining traction across the political spectrum. Some conservatives see it as a way to prevent a race to the bottom and give industries regulatory stability, while progressives view it as a tool to lift wages and standards for all workers. In a labor market where union density has collapsed and inequality has soared, bipartisan interest in sectoral bargaining is a rare opportunity to strengthen worker power at scale.

Unions have long been a cornerstone of American democracy, offering workers a collective voice not only on the job but in shaping a fairer economy and society. They help reduce inequality, strengthen communities, and challenge concentrated economic and political power. Yet union membership is at historic lows, despite equally historic interest in unionization. And too many workers now face stagnant wages, unpredictable schedules, and limited bargaining power.

The nearly century-old National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) offers feeble protections that have been further decimated by courts over decades and is no longer sufficient to protect workers in a fissured, rapidly evolving labor market. Private-sector union density has fallen to about 6%, down from over 30% in the mid-20th century. Meanwhile, CEO pay has increased over 1,200% since the late 1970s, while median wages have barely budged. Achieving comprehensive NLRA reform has proved elusive for decades, despite valiant efforts.

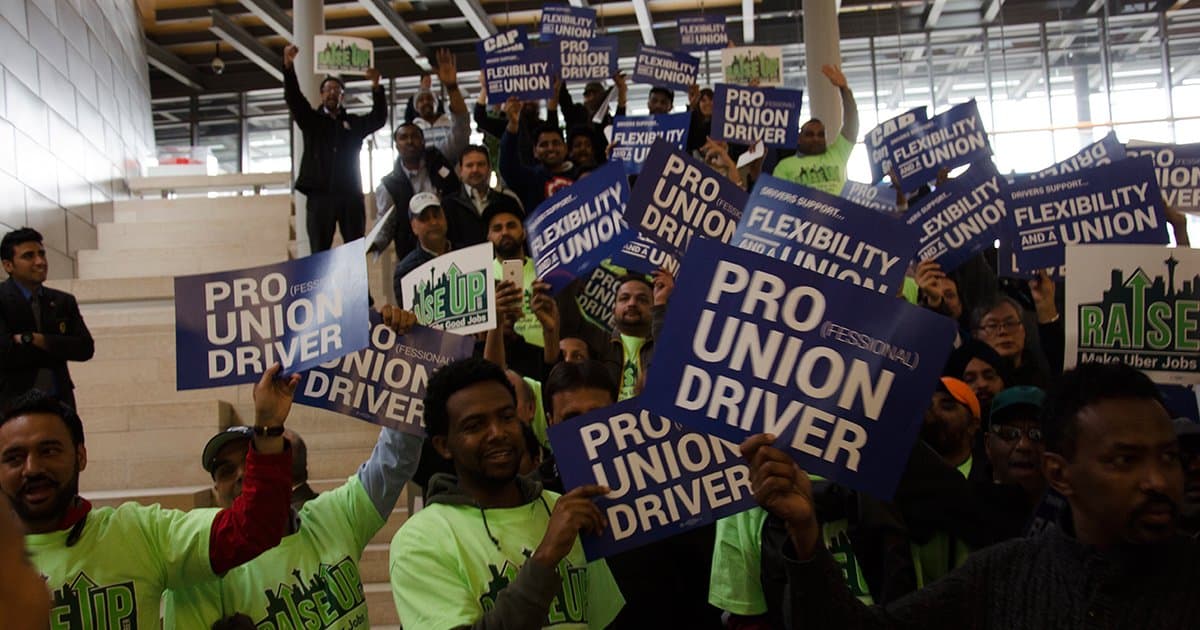

In the face of federal gridlock, states and local governments have been experimenting with sectoral bargaining-style initiatives. New York City’s fast food wage-setting board, California’s fast food council, Seattle’s domestic worker protections, and the Massachusetts rideshare initiative show how sector-wide standards in cities and states can lift conditions and expand bargaining power beyond what single-employer bargaining can achieve — especially for workers excluded from NLRA protections like domestic workers, farmworkers, and gig workers classified (often improperly) as independent contractors.

But current federal labor law and judicial interpretations limit the ability of states and localities to fully realize sectoral bargaining. While the NLRA contains no explicit preemption provision, courts over decades have broadly interpreted the law to limit the power of states and localities to regulate collective bargaining or labor relations. This judicially-created preemption doctrine is expansive, often preventing state and local efforts to create sectoral bargaining frameworks or industry-wide standards for wages, benefits, or working conditions — even though states and cities generally retain authority to set baseline standards like minimum wages or paid leave laws. International experience shows that sectoral bargaining often strengthens union presence and influence, increasing collective power across entire industries, and can strengthen enterprise-level collective bargaining relationships.

Because of the limits of federal preemption, these models often rely on advisory boards or limited wage-setting powers rather than binding, multi-employer collective bargaining agreements that can be extended to additional workers. This means that states and localities often can’t test the full benefits of true sectoral bargaining, such as comprehensive, enforceable contracts covering terms like wages, benefits, scheduling, and grievance procedures across an industry or occupation. Sectoral bargaining, because it involves unions that must be democratic, is representative in ways that worker boards may not be. This makes it more effective at building lasting worker power and ensuring that workers themselves shape the rules that govern their jobs. By leveling the playing field, true sectoral bargaining also pushes employers to compete on the quality of their products and services and affirms that labor is not just an input to be minimized, but an essential output that should be valued and strengthened.

A simple tweak in the NLRA — allowing states and localities to pilot true sectoral bargaining — would empower communities to design fairer labor markets tailored to their needs and realities. Any such legislation should:

- Preserve employees’ rights under the NLRA, including the right to organize, bargain, and engage in protected, concerted activity;

- Ensure the continuation of existing collective bargaining rights, preserving the ability of to negotiate wages, benefits, and working conditions;

- Ensure that sectoral agreements serve as a floor and explicitly permit the negotiation of higher wages and benefits at the enterprise level;

- Provide that sectoral agreements meet or exceed all applicable state, local or federal labor standards;

- Provide financing mechanisms to support bodies that negotiate and enforce sectoral bargaining agreements or provide training, worker education, and other programming; and

- Promote equitable labor standards within a defined industry or sector.

While the bipartisan interest in sectoral bargaining is real, some “New Right” proposals — like those advanced by American Compass — come with troubling and constitutionally questionable strings attached, such as banning unions from political participation. Stripping unions of their political voice while leaving corporate political power untouched would weaken one of the few institutions capable of countering concentrated economic and political influence. At a time when other democratic guardrails are under strain, silencing labor would deepen inequality rather than reduce it.

At its core, sectoral bargaining works best when it strengthens — not weakens — the voice of workers both in the workplace and in our democracy. That’s why proposals that shackle unions’ political role undermine the very purpose of the reform. Instead of narrowing worker power, we should expand it. Allowing states and localities the freedom to pilot full, fair sectoral bargaining models, without unconstitutional political gag rules, would strengthen worker bargaining power, build stronger communities, and strengthen democratic institutions critical to a just economy.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 12

Teamsters sue UPS over buyout program; flight attendants and pilots call for leadership change at American Airlines; and Argentina considers major labor reforms despite forceful opposition.

February 11

Hollywood begins negotiations for a new labor agreement with writers and actors; the EEOC launches an investigation into Nike’s DEI programs and potential discrimination against white workers; and Mayor Mamdani circulates a memo regarding the city’s Economic Development Corporation.

February 10

San Francisco teachers walk out; NLRB reverses course on SpaceX; NYC nurses secure tentative agreements.

February 9

FTC argues DEI is anticompetitive collusion, Supreme Court may decide scope of exception to forced arbitration, NJ pauses ABC test rule.

February 8

The Second Circuit rejects a constitutional challenge to the NLRB, pharmacy and lab technicians join a California healthcare strike, and the EEOC defends a single better-paid worker standard in Equal Pay Act suits.

February 6

The California Supreme Court rules on an arbitration agreement, Trump administration announces new rule on civil service protections, and states modify affirmative action requirements