David Popoola is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

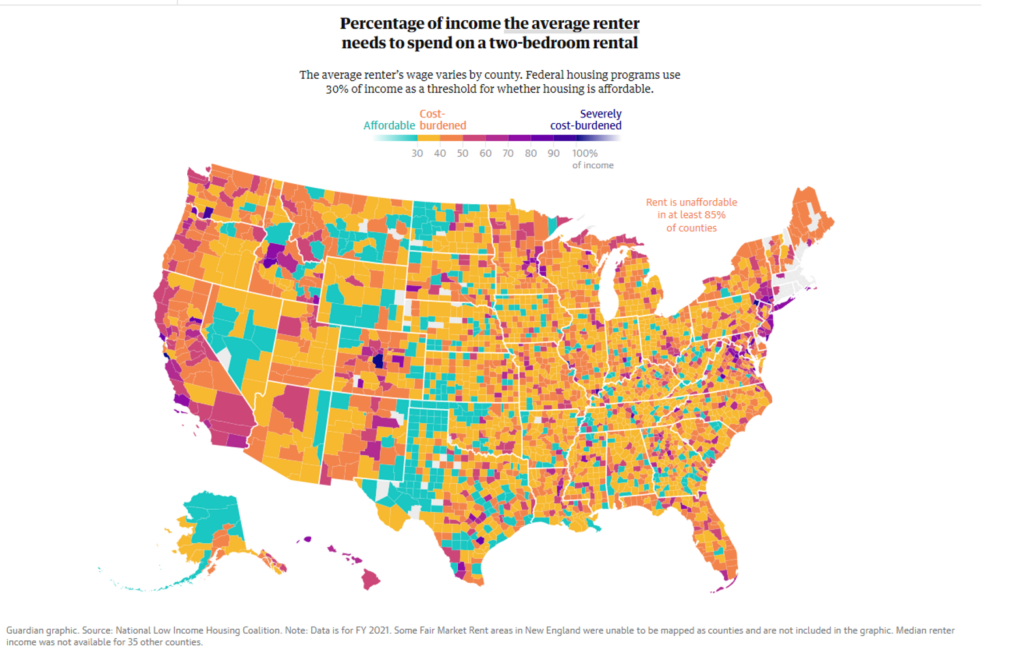

Renters in the United States face a crisis in the growing lack of housing availability and affordability. 70% of the lowest-income renters spent more than half their income on rent in fiscal year 2021. The problem of workers not being able to live where they work is also becoming increasingly acute. In only 7% of U.S. counties could a worker earning minimum wage afford a one-bedroom home at fair market rent in 2021.

In addition to its obvious negative impacts on renters, the increasing unaffordability of housing hurts workers and employers as well: multiple studies have shown that an increased commute time consistently leads to lower job satisfaction and other negative health impacts among workers. Employers interested in their employees’ well-being (or at least concerned about turnover) should be taking notice of this growing disconnect between where employees can afford to live and where they must work. Is it possible that employers could play a role in ensuring that workers who are renters are able to live in affordable housing accessible to their place of work? Some employers have historically done so, and more recently, others such as Google are considering new forays into providing housing for employees.

Contemporary versions of employer-assisted housing have been implemented both by public and private employers and range from highly-integrated models where the employer directly acts as landlord, to less-involved models such as cash transfers, rental subsidies, or letters of credit provided by the employer. If designed with workers’ interests in mind, employer-assisted housing programs have the potential to substantially benefit both employers and employees.

Company Towns

The idea of employer-assisted housing may conjure up memories of the 19th-century “company town,” where all housing and businesses were owned by the employer. In extreme cases, employees were paid in wages usable only in company stores (also known as “scrip”). The driving forces behind the housing aspect of these “company towns” were simple: employers needed to ensure that their workers had a place to live near the worksite (often steel mills and coal mines without permanent settlements nearby). In addition, employers benefitted from the model in that they were able to more effectively monitor employees outside of the workplace, and they were given an additional lever of control over workers’ lives. Pursuant to these arrangements, employers also acted as employees’ landlords, in addition to effectively controlling all the private business and ‘public’ functions and accommodations. Examples of this control being abused abound and are epitomized in the labor strikes that were famously met with violent corporate resistance in the company towns of Homestead, Pennsylvania in 1892 and in Pullman, Illinois in 1894.

A fundamental concern with employer-assisted housing programs that remains largely unchanged from the company town context is the concern that through these programs employers will gain additional coercive influence over employees. Therefore, if employer-assisted housing programs are to be pursued, they must be designed intentionally to ensure that they truly benefit workers, do not unduly empower management, and do not merely recreate the “company town” dynamic.

Contemporary Employer-Assisted Housing

Despite the downfall of the “company town” model, employers have continued to pursue a variety of policies aimed at addressing a part of the same goals: ensuring that their employees have access to housing near where they work, and more insidiously, exerting additional control over the lives of their employees.

Employer as Landlord

The arrangement that most closely resembles the company town model is one where the employer directly acts as the landlord. Several types of employers provide housing in the present day: the National Parks Service houses some employees within its parks, farmworkers are generally housed by their employers, and Google is planning a “campus” in Mountain View, California with office space, residential housing, retail shopping, and many of the trappings of a modern company town.

In these situations, employers play a dual role: both as an employer and as a landlord. From an employer’s perspective, this may be an attractive arrangement in that it ensures that employees are living in housing that is sufficiently close to their workplace and can enable the employer to provide housing at a rental rate below market value to its employees.

However, in substantial ways, this can be an inherently disadvantageous arrangement for renters, particularly if they are fired or otherwise let go from their jobs. Indeed, the prevalence of at-will employment makes the prospect of this form of employer-assisted housing particularly precarious for workers. In a legal regime where the presumption is that one can be fired at any time for no reason at all, having employees’ housing be dependent on their jobs only serves to further empower management vis-à-vis workers, as the threat of firing would also carry with it an implicit threat of eviction, and removal from one’s neighborhood and community. In the best case, termination of one’s employment would be an insurmountable obstacle to a lease’s renewal; in the worst case, termination could lead to the immediate commencement of eviction proceedings. The inverse is also true: housing-related disputes could jeopardize workers’ employment status. For these reasons, employer-assisted housing programs where the employer acts directly as the landlord merit the highest degree of scrutiny to ensure that they do not unduly empower employers.

Financial Transfers/Subsidies

A more arms-length employer-assisted housing arrangement is the provision of housing subsidies or other cash transfers intended for housing as a bonus payment made to employees. The federal government has taken notice of this possibility. In 2007, 2015 and again in 2017, federal legislation was proposed in Congress to provide employers with a tax credit for providing housing assistance. However, in all three instances, the legislation died in committee and did not receive a vote. As housing costs continue to rise and employers continue to feel the consequences of the growing unaffordability of housing, federal legislation of this sort may become more politically feasible.

Other Arms-Length Forms of Housing Assistance

There are even forms of employer assistance that would entail no continuing obligation from the employer to the employee, and that could persist even beyond termination of one’s employment. Examples of this kind of employer assistance include a no-interest loan or one-time subsidy to cover moving or security deposit costs, a rent guarantee or co-sign to enable employees to rent in places where their credit history or income requirements would otherwise prohibit them from renting, or the setting aside of rental units for workers rather than speculators. The major advantages of these forms of assistance are that they cost employers relatively little while being highly valuable to employees without compromising workers’ autonomy.

Conclusion

As housing costs continue to rise across the United States, working-class people will continue to find it more and more difficult to live near their jobs, or to find housing at all. As a solution that could benefit workers and employers both, employer-assisted housing can certainly play a role in addressing this growing crisis, though workers and their representatives must be wary of the “company town” dynamic and programs that empower employers at workers’ expense.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.