Ash Tomaszewski is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

The employee status, and union bargaining rights, of graduate student workers has fluctuated over the last twenty years with the changing of Presidential administrations and the political make-up of the NLRB. But this year is likely to be particularly tumultuous as the agency becomes a center for a pro-labor President’s agenda.

The current state of the law on graduate student bargaining traces back to 2004 and Brown University, where the NLRB decided that graduate teaching assistants, research assistants, and proctors were “students – not employees and that imposing collective bargaining on graduate students would improperly intrude into the educational process.” In 2016, the Board reversed course, holding in Columbia University that student workers meet the definition of “employee.” The decision led to significant unionization and renewed bargaining campaigns at other private universities like Harvard, Yale, Cornell, NYU, Duke, and U-Chicago.

Most recently, in September 2019, the Trump NLRB issued a proposed rule that would reclassify graduate and undergraduate student workers and remove them from the definition of “employee”. Should the rule be finalized, it would more effectively entrench the change than could another Board decision. The NLRB argued that student workers should not have NLRA protections because their primary role is educational and that unionization and collective bargaining “uniquely imperils the protection of academic freedoms” like course content and class sizes, among other policies typically reserved for university administrations and professors. But activists and organizations like the National Education Association have pointed out in public comments that these justifications “cannot be reconciled with the real-world evidence that collective bargaining at public universities has proven both feasible and successful…” and that “[d]ecades of survey-based research shows the vast majority of public university faculty with unionized student workers say collective bargaining doesn’t hinder advising graduate students, developing mentor relationships, or freely exchanging ideas with students.”

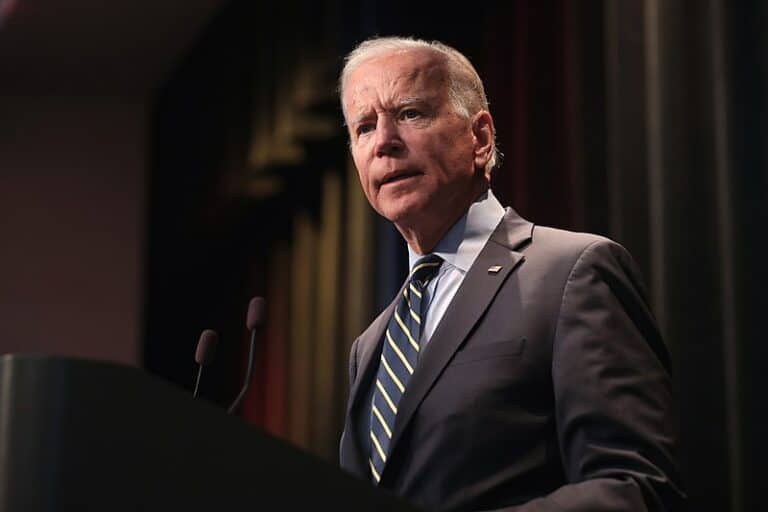

Public comment on the rule ended in March and while the Board indicated in a federal regulatory roadmap released in early December that it would aim to issue its final rule in January, that deadline has since passed without any such finalization. The future for the rule, at this point, seems uncertain. The Biden administration took immediate and strong action in the independent agency by firing general counsel Peter Robb and replacing him with labor-friendly Peter Sung Ohr. This leaves the five person Board with three Republican members until at least August when Trump appointed Bill Emanuel’s term expires. The Morgan Brown & Joy LLP attorney representing Harvard in contract negotiations with HGSU-UAW (Harvard Graduate Student Union), Nicholas DiGiovanni, recently commented that while the agency likely has the power to move forward with rule, it’s currently unclear whether it will.

Prior to President Biden’s election, unions at private universities who were already engaged in bargaining sought to avoid NLRB enforcement of their rights because of the fear that filing unfair labor practice charges would allow the Board opportunity to undermine union bargaining positions. HGSU-UAW President Brandon Mancilla spoke with me on this issue and said, “For the past four years, the Harvard administration has been able to rely on a Trump-appointed NLRB that has kept us from winning a union security shop (despite Massachusetts not being a right-to-work state) and hindered our ability to settle many issues concerning workers’ eligibility for union representation…. We have not taken certain grievances to the NLRB because a ruling unfavorable to student unionization may set a detrimental precedent for other private university student unionization efforts.”

But given the Biden administration’s expected changes to the NLRB, graduate student unions like the GWC-UAW and HGSU are more hopeful, and with this hope comes changes in bargaining strategies. “Biden’s election and his immediate actions regarding the NLRB will usher in new conditions that will embolden academic worker organizing,” Mancilla told me. And on February 1st, GWC-UAW announced they would be establishing a strike deadline at a virtual rally on February 25th to achieve a fair contract, urging the University to move quickly on major proposals. February 25th will mark two years since GWC-UAW began negotiations with the University, a timeline the union describes as “more than enough time to reach an agreement” in a letter to Provost Ira Katznelson. Union leaders defined a fair agreement as “inconceivable” without the following: full recognition of the bargaining unit, union shop and anti-harassment and discrimination protections. The union reminded the University that last Spring they voted 96% YES on a strike authorization vote in what they called a “clear and decisive mandate from a majority of research and teaching assistants at Columbia”.

HGSU, similarly, after securing its first contract last year announced its intent to bargain with the university on Friday, February 12, stating that it is “ready to return to the bargaining table to win the contract we deserve!” HGSU Bargaining Committee member Koby Ljunggren further linked the promise of a union friendly NLRB with strong bargaining goals, stating, “the promise of a pro-union NLRB means not only the fulfillment of grievances and the accountability of the university to our existing contract but also fundamental positive changes to the way our union is supported, institutionally. I have no doubt that these agency changes now exist in the forefront of Harvard’s bargaining strategy.”

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 9

In Today’s News and Commentary, the Supreme Court green-lights mass firings of federal workers, the Agricultural Secretary suggests Medicaid recipients can replace deported farm workers, and DHS ends Temporary Protected Status for Hondurans and Nicaraguans. In an 8-1 emergency docket decision released yesterday afternoon, the Supreme Court lifted an injunction by U.S. District Judge Susan […]

July 8

In today’s news and commentary, Apple wins at the Fifth Circuit against the NLRB, Florida enacts a noncompete-friendly law, and complications with the No Tax on Tips in the Big Beautiful Bill. Apple won an appeal overturning a National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) decision that the company violated labor law by coercively questioning an employee […]

July 7

LA economy deals with fallout from ICE raids; a new appeal challenges the NCAA antitrust settlement; and the EPA places dissenting employees on leave.

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.