John Fry is a student at Harvard Law School.

Now legal for recreational use in 24 states, the cannabis industry has become a major economic force in the United States, employing over 400,000 people. While cannabis is still unlawful under federal law, state-level legalization has made cannabis less of a black market, as run-of-the-mill health codes, employment laws, and other regulations now apply to cannabis businesses.

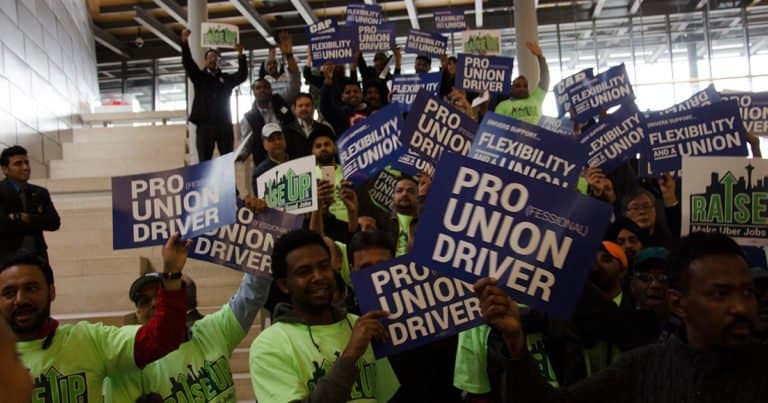

So does the National Labor Relations Act. While some cannabis workers (i.e. those who grow and harvest the plant) are agricultural employees outside the NLRA’s purview, many others who work in dispensaries and processing facilities are subject to federal labor law, as Michelle outlined here. In recent years, unions including the United Food and Commercial Workers and the Teamsters have organized cannabis workers, now representing tens of thousands of them.

Understanding Labor Peace Requirements

But states have also passed their own laws impacting labor relations in the cannabis industry. California law requires any cannabis business with 10 or more employees to enter into a “labor peace agreement” with a “bona fide labor organization,” i.e. a union. Several other states also encourage the agreements in some form in the cannabis industry. A labor peace agreement is a contract between an employer and a union in which the union agrees not to disrupt the employer’s operations, typically by refraining from any strikes, pickets, boycotts, or other campaigns.

On their face, labor peace agreements may appear to hinder unions, because the unions surrender their most powerful forms of collective action. But in practice, employers must offer unions significant concessions in order to get the unions to sign these agreements, often granting the unions the right to organize the employers’ workforces on favorable terms such as card check.

Accordingly, as the Ninth Circuit has observed, unions often advocate for states and cities to require labor peace agreements in certain sectors. Because these agreements transform the playing field for union organizing, states and cities typically craft labor peace requirements to fall within the market participant exception to federal labor preemption (the contours of which I have analyzed here), applying them to government-backed or government-owned ventures like airports and infrastructure projects.

The Ctrl Alt Destroy Case

In April 2024, however, a cannabis retailer named Ctrl Alt Destroy sued to stop California from enforcing the law, on the grounds that it exceeded the scope of the market participant exception and was therefore preempted by federal labor law. The challenge asserts that the state has no proprietary interest in cannabis businesses other than a general desire to collect tax revenue from them, which does not suffice to escape labor preemption.

But earlier this month, Judge Todd Robinson of the U.S. District Court for the Southern District of California dismissed the company’s challenge to the law. The primary basis for the court’s holding was the “unclean hands” doctrine: Ctrl Alt Destroy is a business that exists solely to engage in federally illegal activity (selling cannabis), and striking down California’s law would only make that activity easier. Robinson (a former narcotics prosecutor at the Department of Justice) reasoned that it would be improper for a federal court to facilitate the violation of federal law in this way.

In a footnote, the court also stated that the NLRA does not preempt California’s labor peace requirement. First, Robinson wrote that the law fell under the “local feeling” exception to Garmon preemption, which holds that states may regulate and punish extreme conduct such as violence and intentional torts, even when it is part of a labor dispute. Second, Robinson wrote that Machinists preemption did not apply, because Congress made clear that the “free play of economic forces” should not govern the cannabis industry when it outlawed the drug.

Robinson’s preemption analysis, although developed only in a single footnote, is arguably flawed. The local feeling exception is traditionally understood to apply where NLRA remedies are insufficient to deter or punish serious wrongdoing, and the legal issues to be tried under state law differ from those that the NLRB would examine. Neither rationale applies here: Congress has already banned cannabis, and California’s labor peace law is solely about labor relations, not cannabis or the potential harms associated with it. Furthermore, Machinists refers to “free play” in terms of union and employer tactics unregulated by the NLRA. This concept is unrelated to “free play” in the underlying market for whatever good or service an employer produces, which is what Robinson discusses. The balance of economic power between labor and management (which the NLRA calibrates) has seemingly no effect on whether Congress’ ban on cannabis is observed or flouted.

Implications for Cannabis Workers

However, if other courts follow the “unclean hands” rationale, then these technical preemption questions could be irrelevant. The Ctrl Alt Destroy decision could pave the way for pro-labor state and local governments to boost union organizing and ensure workplace democracy in a fast-growing industry.

Without NLRA preemption, states could enact a wide range of policies, such as prohibiting captive audience meetings, requiring first-contract arbitration, or allowing so-called secondary activity by one employer’s workers against another employer. With overall union membership rates continuing to decline and the cannabis industry on the rise, creative state policy in this area could turn what was once a black market into a success story for worker power.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

March 1

The NLRB officially rescinds the Biden-era standard for determining joint-employer status; the DOL proposes a rule that would rescind the Biden-era standard for determining independent contractor status; and Walmart pays $100 million for deceiving delivery drivers regarding wages and tips.

February 27

The Ninth Circuit allows Trump to dismantle certain government unions based on national security concerns; and the DOL set to focus enforcement on firms with “outsized market power.”

February 26

Workplace AI regulations proposed in Michigan; en banc D.C. Circuit hears oral argument in CFPB case; white police officers sue Philadelphia over DEI policy.

February 25

OSHA workplace inspections significantly drop in 2025; the Court denies a petition for certiorari to review a Minnesota law banning mandatory anti-union meetings at work; and the Court declines two petitions to determine whether Air Force service members should receive backpay as a result of religious challenges to the now-revoked COVID-19 vaccine mandate.

February 24

In today’s news and commentary, the NLRB uses the Obama-era Browning-Ferris standard, a fired National Park ranger sues the Department of Interior and the National Park Service, the NLRB closes out Amazon’s labor dispute on Staten Island, and OIRA signals changes to the Biden-era independent contractor rule. The NLRB ruled that Browning-Ferris Industries jointly employed […]

February 23

In today’s news and commentary, the Trump administration proposes a rule limiting employment authorization for asylum seekers and Matt Bruenig introduces a new LLM tool analyzing employer rules under Stericycle. Law360 reports that the Trump administration proposed a rule on Friday that would change the employment authorization process for asylum seekers. Under the proposed rule, […]