Juan Espinoza Muñoz is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

When I was in 4th grade I was elected Treasurer of the Kiwanis Kids Club where I was in charge of fundraising, writing checks, and bank deposit slips. I quickly used these skills to help my parents navigate bills, mail correspondence, and work documents. I remember going through pay stubs and comparing hours with tally marks on the back of post it notes and scraps of paper mixed with wads of $1’s and $5’s piling out of my dad’s wallet. Working past my cartoon distractions (Recess/Rugrats), my dad would say to me in Spanish – “a ver, fijate bien, creo que me chingaron unas horas” – which means – “hey, pay attention, I think they jacked my hours.”

I dreamed of attending law school in vague permutations of supporting workers, immigrants, and finding ways to redistribute power. But it wasn’t until I joined HLAB’s inaugural class of five Wage-&-Hour (W&H) student attorneys in the spring of 2019 that I realized how much the work would come to mean to me – and how much I would learn as a member and co-director of the practice.

Over the past two years I’ve worked with people who are experiencing wage theft and have chosen to advocate for themselves. The vast majority of our clients are people of color and immigrants who speak little to no English and experience many dimensions of wage theft: they are not paid overtime; have tips withheld; are charged credit-card tip fees of 2-3% that add up to thousands of dollars; are charged for uniforms and equipment; are paid below minimum wage; are not paid accrued vacation that is owed upon termination; are not paid sick leave and obligatory meal and rest breaks; and/or simply are not paid at all. The details of violations and the math are complicated, but the sum is nonetheless simple and devastating.

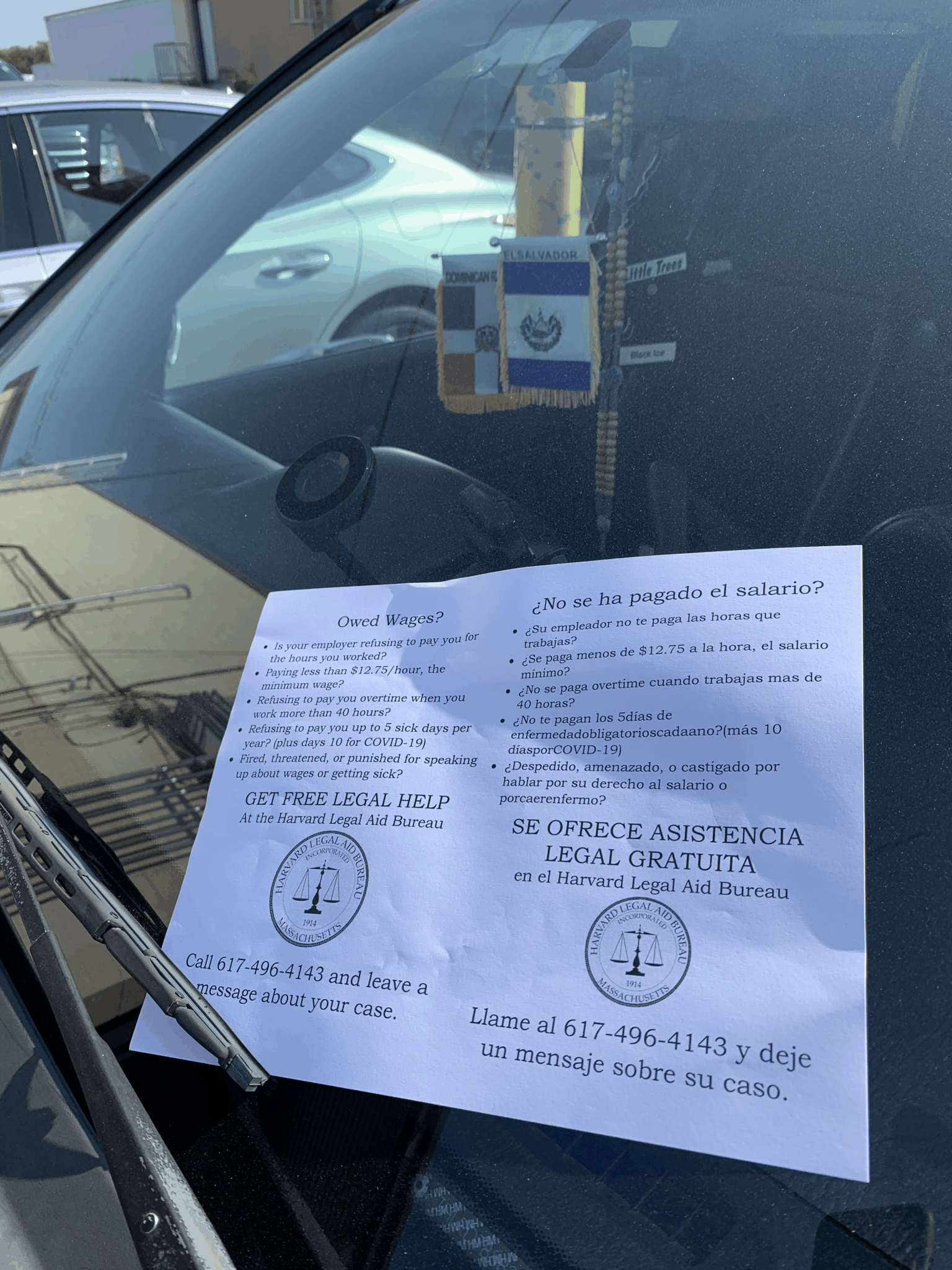

Most of the workers we serve in the practice are from the service industry, construction, restaurants, hotels, small businesses or domestic settings. Most are undocumented workers who have not been paid for work and then consequently threatened with ICE and deportation when confronting an employer. Because of this, ours is a practice that necessitates the building of trust in order to pierce the veil of fear that protects those who abuse their power and steal from workers. We do this while striving to support a broader mission of building worker power, almost all of our cases stem from attending community meetings and conducting intakes through organizing efforts of partners such as the Chelsea Collaborative, Justice at Work, and the Asian Outreach Project.

Often people experience wage theft but are unaware or unwilling to risk retaliation for standing up to an employer – this is likely why each year at least 700 million dollars of wages are stolen in Massachusetts with almost zero accountability. Nationwide, the total wages stolen from workers due to minimum wage violations exceeds $15 billion each year. While wage theft has become an increasingly pervasive problem in recent decades, the number of wage inspectors in the Massachusetts Fair Labor Division has declined in the past 25 years. In 2017 there were 1,849 wage complaints but just 127 enforcement cases in the Boston area. At the Federal level, the U.S. Department of Labor employed 1,000 investigators in 1948 and more recently in 2015 employed fewer than 1,000 investigators despite an increase in the workforce from 23 million to 135 million. From 1980 to 2015 the number of cases investigated by the agency decreased by 63 percent.

This is especially distressing given how wage and hour laws do provide some incentives and proper mechanisms for combating employer theft – and how proper representation and organizing could provide effective deterrence of bad actors and protection for workers. In Massachusetts, when a worker prevails on a wage theft claim – she is granted automatic treble damages, attorney’s fees, and litigation costs. The automatic trebling of damages for employers who commit wage theft has been one of the most important pieces of negotiation in every settlement I’ve secured – and it acts as a layer of protection in the matter of fact way in which it is enforced and supported by case law.

Although we’ve only recently become a full practice in HLAB, students have been taking wage-theft cases for years and secured important victories at the Massachusetts Supreme Court – establishing “prevailing party” status which automatically entitles workers to attorney’s fees in a settlement prior to winning in court. A win that has proven helpful in more readily arriving at a favorable settlement for our clients. Another important case where courts rightfully recognize that the burden should be on the employer, Anderson, confirms that employers are responsible for keeping employee files and documenting work performed for them. Thus, when an employee brings a wage theft claim, if the employer has failed to maintain such records, the burden of proof shifts to the employer. This burden shifting to the employer has been a key point of negotiating settlements, winning judgements, and ultimately recovering stolen wages.

It’s hard for me to believe that our group of 9 student attorneys is the largest entity of free legal services providers solely dedicated to fighting wage theft in Boston – we’ve supported the recovery of $165,000 in wage theft over the past year. While this might seem meager compared to $700 million in wages stolen per year, I am proud of a small but mighty team that worked through tragedies of power and illness where we saw workers get empty checks from restaurants that closed, day laborers robbed during the boom of home renovations, and immigrant women laid off due to Covid hospitalizations and caring for family after having worked for an employer for 25 years packing produce. We found light in Valentine’s Day ice breakers about first dates, cute photos with pets, and sharing stories. I learned to look forward to weekly meetings where we problem-solved, conducted intake, and carried each other forward.

But perhaps the most important lesson I’ve learned is that the Wage and Hour Practice goes far beyond “getting money from employers” – it engages in the more arduous work of recovering dignity, respect, and the self-worth of employees. What I will most cherish from my time in HLAB – are the interactions I’ve had with people who are brave enough to fight back. It is a feeling that comes when my clients look me in the eyes and express a sincere gratitude for having a companion in fighting back. It comes when clients express a sincere eagerness and humility – it comes when they express a cautious deference to the (barely earned) power of the student attorney sitting in front of them. It reminds me of the questions my dad asked me as a kid when I would help him navigate his paperwork – cautious, genuine, trusting, and vulnerable. It throws me into a spin of memories that I have to contain every time I interact with a client. It reminds me that a part of this work to me is also a search for home – and my own desire to be there for people the way I wish others had been there when my parents experienced wage theft as immigrants in this country.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

April 25

FTC bans noncompete agreements; DOL increases overtime pay eligibility; and Labor Caucus urges JetBlue remain neutral to unionization efforts.

April 24

Workers in Montreal organize the first Amazon warehouse union in Canada and Fordham Graduate Student Workers reach a tentative agreement with the university.

April 23

Supreme Court hears cases about 10(j) injunctions and forced arbitration; workers increasingly strike before earning first union contract

April 22

DOL and EEOC beat the buzzer; Striking journalists get big NLRB news

April 21

Historic unionization at Volkswagen's Chattanooga plant; DOL cracks down on child labor; NY passes tax credit for journalists' salaries.

April 19

Alabama and Louisiana advance anti-worker legislation; Mercedes workers in Alabama set election date; VW Chattanooga election concludes today.