Fred Wang is a student at Harvard Law School.

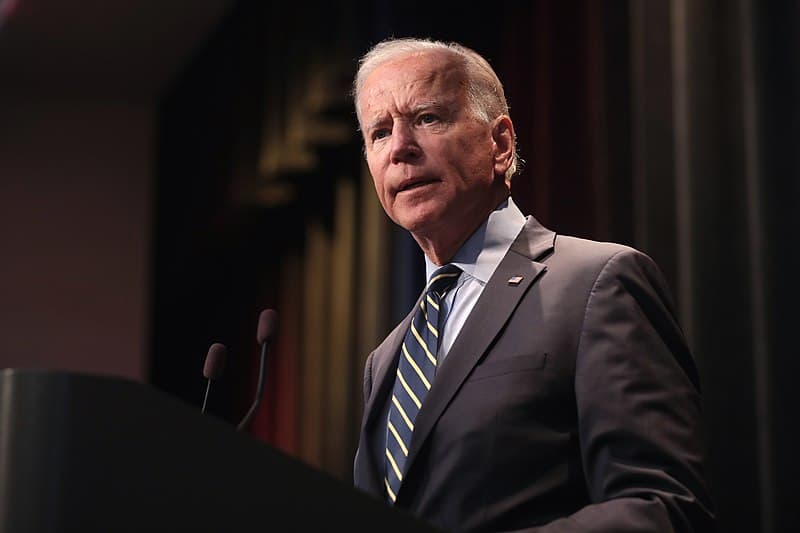

At the early outset of his administration, President Biden—in keeping with his pledge to be “the most pro-union president you’ve ever seen”—fired the National Labor Relation Board’s general counsel, Peter Robb, after Robb—a pro-management Trump appointee and now the first NLRB general counsel to be dismissed in decades—refused the President’s request to resign ten months before his term was to expire. In Robb’s stead, Biden named career NLRB lawyer Peter Ohr to the helm—who, in his first week as acting general counsel, reversed course on a series of Trump-era agency policies and positions. However, in the immediate wake of such moves, companies in pending litigation with the NLRB have already begun filing briefs that raise objections to Acting GC Ohr’s legal authority on grounds that Robb’s termination was unlawful.

The case being made against Robb’s removal is strained and unpersuasive, both on its face and in light of precedent. The briefs that have been filed thus far consist of two principal claims: (1) the text of the National Labor Relations Act precludes the President from removing the general counsel at will prior to the end of the GC’s term; and (2) the purpose of the NLRB as a quasi-judicial independent agency would be ill-served if the President retained plenary removal authority over the general counsel. Each will be discussed in turn—neither offers a convincing legal basis for challenging Robb’s dismissal.

First, challengers contend that the plain language of the NLRA shields the general Counsel from removal without cause, notwithstanding the fact that Section 3(d)—which establishes the office of the general counsel—contains no explicit removal provision, while Section 3(a)—which states that no “member of the Board” may be removed for any cause other than “neglect of duty or malfeasance in office”—does. In essence, they argue that because Section 3(d) describes the general counsel as “of the Board” and with the final authority to act in certain contexts “on behalf of the Board,” the general counsel is effectively a member of the Board and therefore subject to Section 3(a)’s for-cause removal protections.

This argument is dubious. For one, if the enacting Congress truly wanted to shield the general counsel from at-will presidential removal authority, it is unlikely that it would have done so in such an obscure and subtle manner. Moreover, as a functional matter, the claim is inaccurate. The modern design of the NLRB entails a structural division of labor within the agency, whereby the Board and the general counsel perform distinct roles. While the NLRA enables the Board to execute quasi-legislative and quasi-judicial functions—for instance, Section 5 authorizes the Board to promulgate regulations and Section 9(b) sanctions it to adjudicate unfair labor practice cases—it largely empowers the general Counsel to perform quintessentially executive prosecutorial functions: to investigate complaints and prosecute charges of unfair labor practices.

Finally, as a textual matter, the general counsel, plainly put, is not a member of the Board. It is clear that when the NLRA refers to “members” of the Board, it is exclusively describing the five appointees on the Board itself, not the general counsel. Section 3(a), for instance, says that the Board shall consist of five “members”—not “six members, including the General Counsel.” Similarly, Section 4(a) treats the two positions as distinct, stating that “[e]ach member of the Board and the General Counsel of the Board” are eligible for reappointment. If the challengers’ construction of the statute—that “members of the Board” also referred to the general counsel—were accurate, such a formulation distinguishing the two would be redundant.

Furthermore, the absence of an explicit removal provision in Section 3(d) does not entail that the general counsel must be allowed to serve the entire duration of their four-year term. As the Supreme Court established long ago in Parsons v. United States, a statutory provision that specifies a prosecutor’s term length does not itself bar the President’s ability to remove her in the middle of her tenure.

Textual considerations aside, challengers also claim that at-will presidential removal of the general counsel is inconsistent with Congress’s intention that the NLRB function as a quasi-judicial independent agency. The argument is that the absence of removal protections on the general counsel allows inappropriate political considerations to vitiate what should be the “neutral and even-handed” resolution of labor disputes by an independent body.

The relevant legislative history behind the creation of the GC position offers some support for this contention. The establishment of the GC office can be traced, in part, to congressional anxieties about pro-union NLRB conduct and an attendant desire to curb agency overzealousness by internally separating the agency’s prosecutorial functions (to be carried out by the General Counsel) from its adjudicatory ones (to be executed by the Board).

However, this same prosecution-adjudication distinction presents significant problems for the challengers’ legal case. First, this distinction supplies a coherent explanation for why Congress included removal protections for members of the Board, but not for the general counsel. Second, and more importantly, the Supreme Court’s recent treatment of this distinction in the context of other administrative agencies strongly indicates that removal protections for the general counsel would not even be constitutional in the first place. Last June, in Seila Law v. CFPB, the Court held that when it comes to the removal of “purely executive officers”—as opposed to “quasi-judicial” or “quasi-legislative” multi-member bodies—with enforcement authority to seek penalties against private parties on behalf of the United States, the President holds “unrestrictable power.” In fact, the Court in Seila, as if it were speaking presciently to the present controversy at hand, explicitly lamented the idea of an “unlucky President” elected on a certain platform entering office “only to find herself saddled with a holdover Director from a competing political party who is dead set against that agenda.”

Therefore, as it currently stands, the legal case against Robb’s firing remains, on the merits, tenuous. Indeed, many have cast doubt that the attacks will amount to anything more than a time and resource drain for the NLRB, even if the Court ultimately rules that Robb’s dismissal was illegal. After all, should the Court choose to nullify Ohr’s actions on grounds that the GC position was improperly vacated, whomever Biden successfully nominates to the general counsel post as Ohr’s successor can simply ratify whatever voided complaints and decisions Ohr originally issued. Such was the case in 2017 when then-General Counsel Richard Griffin ratified actions by his predecessor, Acting General Counsel Lafe Solomon, that the Court had invalidated in NLRB v. SW General on grounds that Solomon was ineligible to serve in an acting capacity after he had been nominated by President Obama to fill the vacancy permanently. Thus, while the legal challenges to Robb’s removal are here to stay and will certainly persist, such efforts—in light of the relevant case law and present disposition of the Court—will surely be unavailing.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 22

A petition for certiorari in Bivens v. Zep, New York nurses end their historic six-week-strike, and Professor Block argues for just cause protections in New York City.

February 20

An analysis of the Board's decisions since regaining a quorum; 5th Circuit dissent criticizes Wright Line, Thryv.

February 19

Union membership increases slightly; Washington farmworker bill fails to make it out of committee; and unions in Argentina are on strike protesting President Milei’s labor reform bill.

February 18

A ruling against forced labor in CO prisons; business coalition lacks standing to challenge captive audience ban; labor unions to participate in rent strike in MN

February 17

San Francisco teachers’ strike ends; EEOC releases new guidance on telework; NFL must litigate discrimination and retaliation claims.

February 16

BLS releases jobs data; ILO hosts conference on child labor.