Tamara Shamir is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

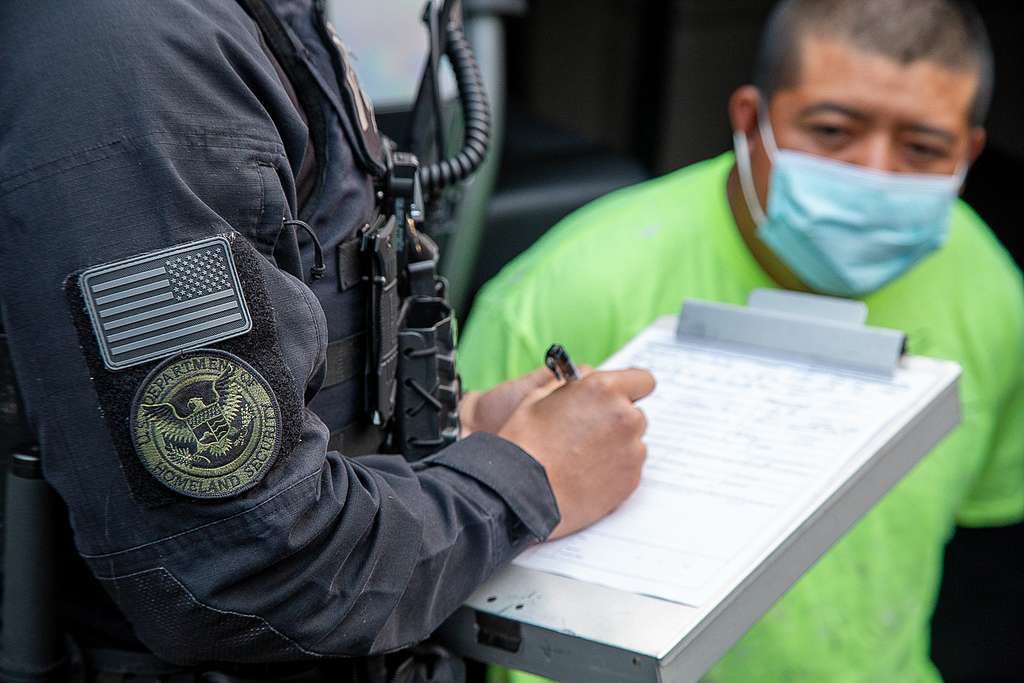

In its final minutes in power, the increasingly anti-immigrant Biden administration snuck in a buzzer-beating act of mercy: extending Temporary Protected Status (TPS) for immigrants from four countries. In early February, President Trump’s Department of Homeland Security reversed these protections, threatening roughly a million immigrants with the loss of their legal status.

The gravity of the reversal was largely drowned out by the broader wave of xenophobic policies that continues today. Yet Trump’s reversal not only put hundreds of thousands of TPS recipients at risk of deportation, but also threatened to strip them of basic labor protections.

TPS has always been a fragile lifeline for immigrants fleeing danger in their home countries. The status is granted by the U.S. government to nationals of countries experiencing crises, allowing TPS recipients to live and work legally in the U.S. as long as their home country remains designated. Seventeen countries currently have TPS designations. Unlike most humanitarian protections for immigrants, TPS does not offer a path to permanent residency or citizenship; its recipients are therefore unusually vulnerable to the whims of political disfavor.

The government’s broad discretion over TPS is not limitless, however. A group of Venezuelan and Haitian migrants recently sued the Trump administration, claiming that the revocation of TPS was capricious and racially motivated—the same claims that had allowed TPS holders to secure reprieve during the first Trump administration. California district judge Edwards M. Chen, who also heard the TPS cases in 2018, issued a preliminary injunction protecting Venezuelan TPS recipients on March 31st. His ruling provided about 600,000 Venezuelans with temporary relief. Judge Edwards, however, has yet to issue a similar ruling for the hundreds of thousands of Haitian TPS holders slated to lose their protections by the end of this summer. Around 500,000 Haitian immigrants rely on the status to live and work with documentation in the United States.

While the lawsuit challenging Trump’s termination of TPS is framed in terms of administrative procedure and protections against invidious stereotyping, its most immediate stake is preventing the mass loss of work authorization. For most, losing TPS would mean losing the ability to work with authorization. Some TPS holders may have access to other forms of protections which would preserve their work permit, including asylum — although only 4% of Haitian asylum cases and less than 30% of Venezuelan asylum cases end in an asylum grant. Removing TPS protections would push hundreds of thousands into the shadows of the labor market, formally stripping them of some rights while practically removing others.

“There are very limited ways for people to get status in the United States,” Mariam Liberles, an attorney with the Harvard Immigration and Refugee Clinical Program, told OnLabor. If Haitian former TPS-holders don’t prevail in the lawsuit, she explained, “they could be left with nothing. They could literally lose everything.”

Losing work authorization will leave many immigrants with highly circumscribed employment opportunities, escalated job instability, and wage suppression. It will also leave them without a way to assert their rights as workers. Although undocumented workers remain formally protected under the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA), the remedies available to them are limited. Employers often exploit undocumented workers by underpaying them or subjecting them to unsafe working conditions, a reality intensified by the Trump administration’s aggressive approach to immigration enforcement.

In 2002, the Supreme Court held that undocumented workers fired for unionizing could not receive back pay. Enforcing undocumented immigrants’ right to receive unlawfully withheld wages would, the Court reasoned, “condone” and “encourage” violations of immigration law. Specifically, it would conflict with the Immigration Reform and Control Act (IRCA), which prohibits employers from knowingly hiring unauthorized workers.

The decision handicapped undocumented workers’ ability to participate in unions—and triggered a rapid erosion of undocumented immigrants’ workplace rights. Over the last two decades, questions about immigrants’ status have proliferated in employment suits, putting workers who choose to come forward with claims at a far higher risk of detection and therefore removal from the country. Undocumented workers themselves are forced to choose between reporting workplace abuses (risking employer retaliation and deportation) or enduring unsafe or exploitative conditions. Their vulnerability to removal cleaves them from the rights they could otherwise exercise as workers.

****

In his March 31st ruling, Judge Chen seemed cognizant of this consequence: the administration’s racially-motivated and illegal action could, the judge wrote, not only “cost the United States billions in economic activity,” but also “inflict irreparable harm on hundreds of thousands of persons whose lives, families, and livelihoods will be severely disrupted.” The Trump administration’s decision to rescind TPS for Venezuelans, moreover, appeared to be “predicated on negative stereotypes casting class-wide aspersions.” Chen criticized the government’s insinuations that Venezuelan TPS-recipients “were released from Venezuelan prisons and mental health facilities and imposed huge financial burdens on local communities,” finding that the reversal of TPS was motivated by racial animus. Moreover, Chen wrote, the U.S. government could not credibly designate Venezuela as a “safe” country for TPS purpose when the country is “so rife with economic and political upheaval and danger” that it has been categorized as Level 4: Do Not Travel by the State Department.

The safety secured by the preliminary injunction is fragile even for the Venezuelans who received it. Even with a court order upholding the work permit of some of these immigrants, Liberles said her clients remain “in limbo.” “It’s nerve-wracking, not knowing what will happen,” she said.

The nearly half a million Haitian TPS recipients slated to lose protection in a matter of months remain in deeper limbo still, uncertain whether the revocation of their TPS status will be enjoined. The ultimate outcome of the Venezuelan and Haitian TPS recipients’ suit could determine whether around a million immigrant workers hold on to their work permits and the rights it helps secure: to unionize without penalty, to sue for wage theft, to denounce unsafe or discriminatory workplaces.

Even if TPS recipients prevail once again in thwarting Trump’s attack through the courts, some of the harm intended has already been done. The uncertainty itself is effective no matter the suit’s outcome: it keeps around a million workers insecurely tethered to their labor and their rights. The court may decide whether TPS recipients preserve their work permits—but it has already underscored their precarity.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

January 28

Over 15,000 New York City nurses continue to strike with support from Mayor Mamdani; a judge grants a preliminary injunction that prevents DHS from ending family reunification parole programs for thousands of family members of U.S. citizens and green-card holders; and decisions in SDNY address whether employees may receive accommodations for telework due to potential exposure to COVID-19 when essential functions cannot be completed at home.

January 27

NYC's new delivery-app tipping law takes effect; 31,000 Kaiser Permanente nurses and healthcare workers go on strike; the NJ Appellate Division revives Atlantic City casino workers’ lawsuit challenging the state’s casino smoking exemption.

January 26

Unions mourn Alex Pretti, EEOC concentrates power, courts decide reach of EFAA.

January 25

Uber and Lyft face class actions against “women preference” matching, Virginia home healthcare workers push for a collective bargaining bill, and the NLRB launches a new intake protocol.

January 22

Hyundai’s labor union warns against the introduction of humanoid robots; Oregon and California trades unions take different paths to advocate for union jobs.

January 20

In today’s news and commentary, SEIU advocates for a wealth tax, the DOL gets a budget increase, and the NLRB struggles with its workforce. The SEIU United Healthcare Workers West is advancing a California ballot initiative to impose a one-time 5% tax on personal wealth above $1 billion, aiming to raise funds for the state’s […]