Vail Kohnert-Yount is a student at Harvard Law School.

On Wednesday, Congress passed the first widespread federal paid sick leave mandate within its coronavirus emergency relief package. Only a massive pandemic—current estimates predict, at a minimum, hundreds of thousands of deaths in the United States—could convince Congress to enact even a temporary paid sick leave measure.

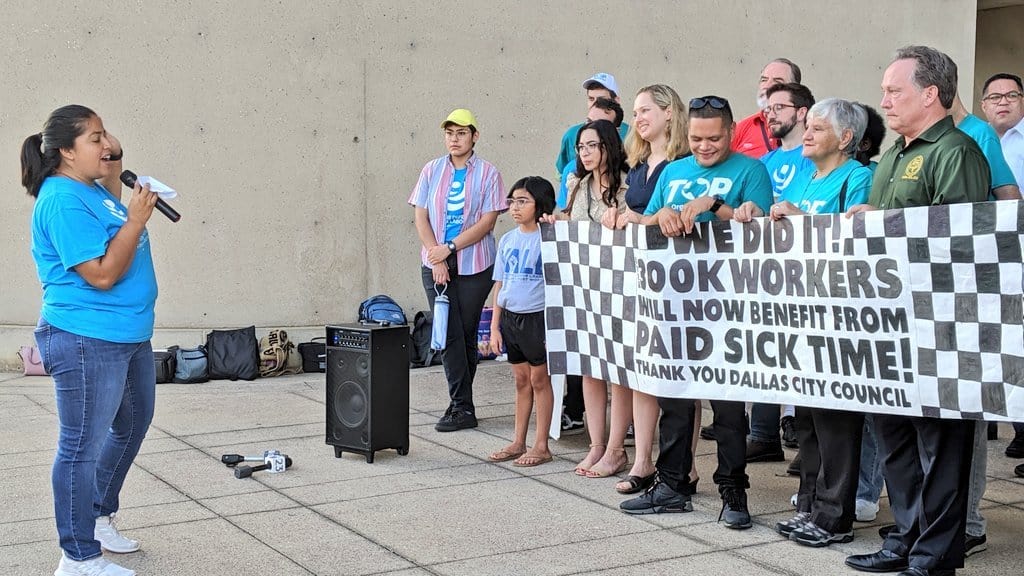

Since 2011, states and cities have acted on paid sick leave where Congress has failed. Thirteen states have passed laws expanding access to paid leave to 16 million people. Even in hostile states like Texas, local governments have followed suit. Last year, Dallas became the first city in the South to implement paid sick leave.

Despite reams of evidence showing that these laws benefit public health by helping slow the spread of coronavirus and other diseases, local paid sick leave ordinances remain under constant attack in states like Texas. Although these local laws don’t and can’t effectively protect the entire workforce, they will continue to benefit many workers who will be left behind by the new federal law.

Everything’s Bigger in Texas—Except the Number of Workers with Paid Sick Leave

As Texas confronts coronavirus, with 325 cases statewide and counting, the state may be especially vulnerable to community spread because of a widespread lack of paid sick leave. Since 2018, three of Texas’s four largest cities—Austin, Dallas, and San Antonio—have passed local paid sick leave ordinances. However, only the Dallas law has gone into effect, as legal challenges over preemption have temporarily blocked the other ordinances, leaving tens of thousands of San Antonio and Austin workers who could have paid sick leave without it.

About 40% of Texas workers are unable to take paid sick leave from work, according to the Workers Defense Project and Institute for Women’s Policy Research, compared to 24% of workers nationwide. The numbers are worse in the service industry, where 78% of workers, from restaurant servers to home health care aides, lack paid sick days.

Even those workers who have paid leave are often unable to use it, especially in a crisis. At least one major national employer based in Texas, Houston multi-billionaire Tilman Fertitta, even tried to rescind vacation and sick days from some of his companies’ employees, citing coronavirus—although he backed off after employees went public.

Local Paid Sick Leave Ordinances Face an Uncertain Future in Texas

Austin was the first Texas city to enact paid sick leave in early 2018, but its ordinance was enjoined later that year and never went into effect. Although the city argued that its ordinance is entirely consistent with state minimum wage law, the Third Court of Appeals nevertheless held that it was preempted by the Texas Minimum Wage Act. Austin appealed to the Texas Supreme Court, which hasn’t yet decided whether to review the case. If it does, the timeline for a ruling is unclear—especially since the Court closed this week due to coronavirus concerns.

The San Antonio City Council passed paid sick leave in summer 2018, after more than 144,000 signatures were gathered to force a ballot initiative on the subject. Like Austin, the San Antonio ordinance never went into effect. It has been subject to a temporary injunction since November 2019, as the city considers whether to appeal to the Fourth Court of Appeals.

Dallas followed suit, becoming the first and only Texas city to actually implement paid sick leave in August 2019. The Texas Public Policy Foundation, a conservative advocacy group that brought the lawsuits against the cities of Austin and San Antonio, also filed a federal lawsuit against Dallas two days before the ordinance went into effect.*

Texas Attorney General Ken Paxton intervened in all three lawsuits on behalf of the plaintiffs, arguing that paid sick leave is merely “the agenda of urban elites.” While litigation is pending in the Eastern District of Texas, TPPF has defended the Trump administration’s “prudent” coronavirus response, writing that “America will emerge just fine after the epidemic passes, and with some lasting benefits.”

Thus far, only one state appellate court has held that state law preempts paid sick leave ordinances. But because it’s uncertain whether or not the Texas Supreme Court will agree, Republican state lawmakers attempted—but failed—to pass legislation specifically banning local paid sick leave ordinances before the 2019 legislative session ended.

Workers in Texas—and Everywhere—Need State and Federal Government to Step Up

By definition, local paid sick leave ordinances are limited in scope. For example, because many types of workers are excluded, the Dallas ordinance covers only a fraction of the estimated 3,870,400 non-farm workers in metropolitan Dallas-Fort Worth. It applies only to individuals who perform “at least 80 hours of work for pay within the City,” or about 300,000 employees, excluding government employees and workers classified as independent contractors. The ordinance doesn’t apply to employers with five or fewer employees until 2021.

Although the ordinance has been in effect since August 2019, Dallas will only begin enforcement next month. Cities are generally prohibited from enacting ordinances that create private causes of action, so local ordinances like Dallas’s can only be publicly enforced. The Dallas ordinance will fine employers $500 per violation, to be determined by the city. It remains to be seen whether this enforcement mechanism will be effective.

At best, well-enforced local paid sick leave ordinances can benefit many workers who would otherwise be left behind. The federal emergency relief package only temporarily grants workers paid leave if they must take time off because of coronavirus—but it curiously exempts all companies with more than 500 employees, excluding 48% of American workers. But employees of these major employers based in cities like Dallas and Duluth or states like New Jersey and Nevada will at least have some mandated leave.

Paid sick leave opponents, from the Texas Public Policy Foundation to the Chamber of Commerce, have long argued that local leave ordinances create a “patchwork” of standards too “challenging” for multinational corporations to comply with. However, these same opponents also fight state and federal paid sick leave laws, arguing that businesses—especially small businesses—should not have to bear the cost.

Indeed, the Chamber urged Congress to reject any paid leave in coronavirus emergency legislation, citing the “impact” on small business. Ultimately, the bill’s provisions were significantly diminished under pressure from the Chamber and other corporate interest groups. Ultimately, the Chamber was perfectly fine with letting big business play by a different set of rules than small employers, exposing where its loyalties really lie. Meanwhile, Senate Republicans have already begun trying to water down the paid leave they just passed.

More than ever before, the coronavirus pandemic shows that all workers need paid sick leave. To fight the outbreak in Texas, Ken Paxton and corporate interest groups must drop their lawsuits against Texas cities. The least the state government can do, if it won’t help Texas workers by passing statewide paid sick leave, is to get out of the way of cities doing their best.

Cities like Houston, the largest U.S. city without paid sick leave, have both the power and the moral duty to enact paid sick leave in response to coronavirus. Although the hope is that “America will emerge just fine,” hundreds of people have already died. If any “lasting benefits” can survive this pandemic, paid sick leave should be one of them.

* Update: On March 30, two days before the City of Dallas was set to start enforcing its local paid sick leave policy, a federal judge in the Eastern District of Texas issued an injunction.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.

July 1

In today’s news and commentary, the Department of Labor proposes to roll back minimum wage and overtime protections for home care workers, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit by public defenders over a union’s Gaza statements, and Philadelphia’s largest municipal union is on strike for first time in nearly 40 years. On Monday, the U.S. […]

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]