Jason Vazquez is a staff attorney at the International Brotherhood of Teamsters. He graduated from Harvard Law School in 2023. His writing on this blog reflects his personal views and should not be attributed to the IBT.

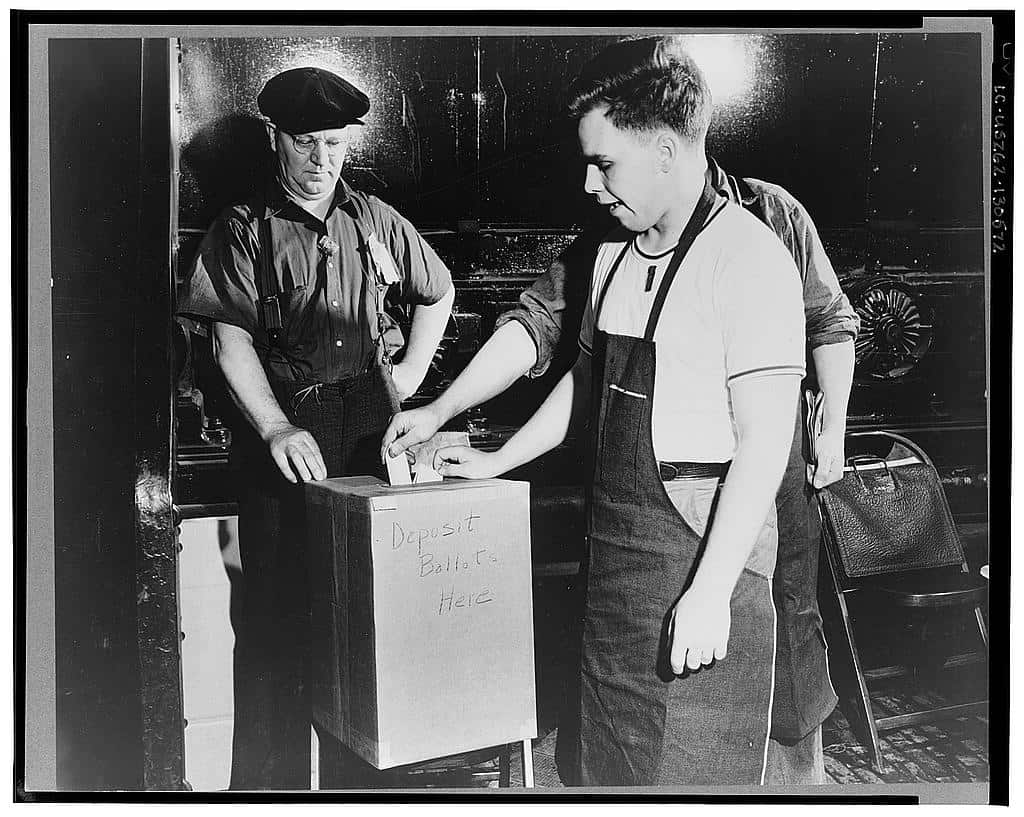

Labor unions have historically had an enormously democratizing effect on society. In a political economy dominated by private ownership of capital and immense concentrations of wealth, they stand out as a commendable example of a participatory and democratic social institution. Indeed, in contrast to corporations, which are, as I observed last month, utterly despotic entities, federal law mandates that unions must operate democratically.

However, notwithstanding laudable efforts in recent years to become even more participatory and inclusive, the reality is that unions remain imperfectly democratic institutions. Indeed, research has suggested that many major unions, although “firmly democratic,” tend to exhibit certain tendencies of oligarchies or autocracies. This is concerning because, as one labor scholar has explained, democracy is “the very foundation of union power.” Studies have found that “the contracts won by … highly democratic unions … [are] systematically more likely to be pro-labor,” and that “union democracy increases union effectiveness in representing members’ interests and in mobilizing these members to support its collective bargaining agreements.” For these reasons, some academics and progressives have suggested that further democratizing labor unions would not only strengthen existing unions but revitalize the gasping labor movement.

The U.S. labor movement has its genesis in the early 20th century, when labor activists, many of them socialists and communists, employed highly militant and disruptive tactics to subordinate powerful firms and organize millions of working people. In the subsequent decades, with help from the protections conferred by federal labor law, unions became bigger and more powerful, yet also more institutionalized and bureaucratized. Some began to prioritize securing contracts that protected their existing membership over fresh organizing and economic disruption. Additionally, in recent decades, as the destructive neoliberal regime dismembered organized labor, national unions increasingly began to merge and absorb local ones. As a result of these pressures, today’s labor movement is highly centralized, dominated by a handful of national organizations that often display imperfect democratic tendencies.

Large and powerful labor organizations are not automatically undemocratic, and they are necessary to countervail the enormous concentrations of private capital. However, the reality is that displacing the elected leader of one of today’s large national unions is often an all but impossible task. Only four of the largest unions have adopted a direct voting system, and it is not uncommon for top officer elections in many major unions to be barely contested or even entirely uncontested. In fact, a challenger has not unseated an incumbent president in any of the largest unions in decades. To be sure, labor unions have a decentralized and federated structure, and local affiliates are often more democratic than their national parent organizations. Regardless, there is reason to believe that the absence of meaningful democratic engagement at the highest levels of the labor movement can give rise to a disconnect between union membership and union leaders. In 2016, for example, many union members favored Bernie Sanders in the Democratic presidential primary, but the executive boards of major unions endorsed Hillary Clinton. As labor leaders later conceded, union officials had “underestimated the amount of anger and frustration among working people.”

The Association for Union Democracy (AUD), a national non-profit organization, has compiled a helpful list of union democracy benchmarks. These factors encapsulate the basic conditions necessary for genuine union democracy. AUD, first and foremost, suggests that unions must hold frequent — and contested — direct elections, in which members challenge incumbents and incumbents are routinely displaced. Moreover, AUD suggests that union leaders must encourage members to run and secure them time off to campaign, and that all union representatives and shop stewards should be directly elected and subject to recall. Next, AUD recommends that the union publish a newsletter explaining the union’s policies and printing members’ views and holds regular meetings in which members are encouraged to discuss important issues. Lastly, the membership should vote on all decisions regarding strikes.

The struggle for organized labor has historically been a struggle for the working class to assert more control over their lives — a struggle, in other words, for democracy. Indeed, the labor movement has been and remains an impressive force for democracy and social justice, and to advocate for more democracy in unions is not to suggest that they are presently undemocratic, only that they are imperfectly democratic. In the final analysis, the capacity of labor unions to democratize society will increase to the extent that workers enjoy greater democracy in unions themselves.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 6

Municipal workers in Philadelphia continue to strike; Zohran Mamdani collects union endorsements; UFCW grocery workers in California and Colorado reach tentative agreements.

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.

July 1

In today’s news and commentary, the Department of Labor proposes to roll back minimum wage and overtime protections for home care workers, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit by public defenders over a union’s Gaza statements, and Philadelphia’s largest municipal union is on strike for first time in nearly 40 years. On Monday, the U.S. […]

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.