Dr. David Doorey is an Associate Professor of Labor and Employment Law at York University in Toronto.

U.S. labor law professors have long looked north of the border for ideas on how to breathe new life into the ‘ossified’ National Labor Relations Act. This outward gaze was inspired by Paul Weiler, Canada’s greatest labor law export, who moved to Harvard Law School in the late 1970s after a distinguished career in Canadian labor law. In his celebrated 1983 Harvard Law Review article “Promises to Keep: Securing Workers’ Rights to Self-Organization Under the NLRA” and his 1990 book Governing the Workplace: The Future of Labor and Employment Law, Weiler argued that differences in Canadian labor law explained much of the divergent fortunes of collective bargaining in the two countries.

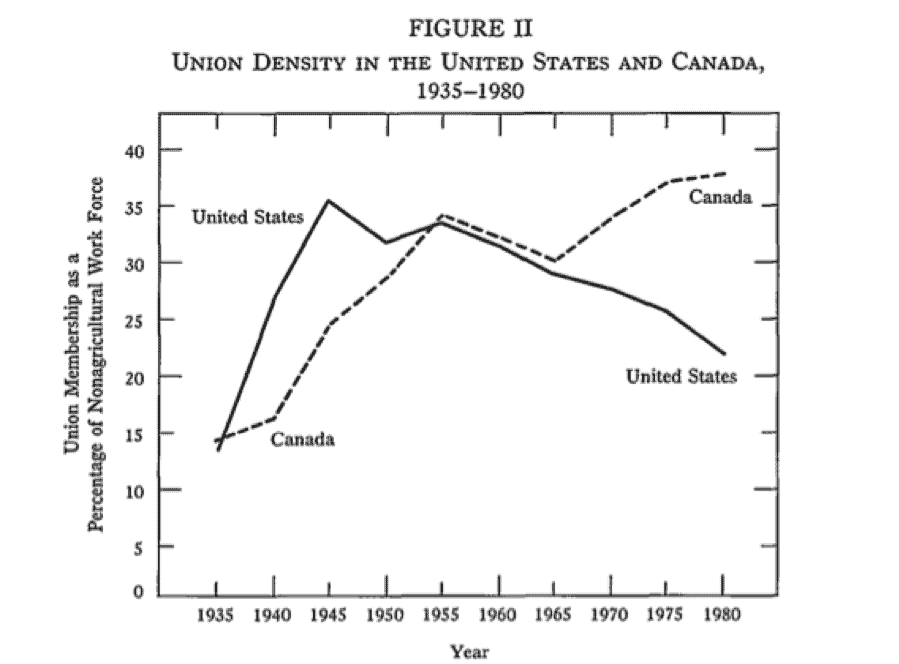

Weiler was writing in the 1980s when union density in the U.S. sat near 15 percent, down considerably from its peak decades earlier. To arrest this fall and revitalize collective bargaining, Weiler proposed a series of reforms, many drawn from Canada, where union density remained over 35 percent, a startling comparative statistic that Weiler depicted in the following chart in “Promises to Keep”.

Canada as a Model for NLRA Reform: The Old Story

In Canada, labor law falls primarily within the jurisdiction of the provinces, rather than the federal government. However, there is sufficient homogeneity across jurisdictions that it is fair to speak of a “Canadian Wagner model”. Weiler’s premise was that law mattered greatly to union density and that the Canadian model did a better job of controlling employer resistance to union organizing than did the NLRA. In particular, Weiler noted that most Canadian jurisdictions determined majority employee support for collective bargaining by means of a card-check model, which eliminated much of the opportunity for both lawful and unlawful employer resistance to unionisation. However, Weiler doubted that U.S. employers would ever accept the outcome of a process without elections, so he proposed Canada’s alternative “instant ballot” model for the U.S., which requires a certification vote within a short period after an application for certification.

Weiler criticized the slow and weak response by the NLRB to employer unfair labor practices (ULP). ULP complaints were dealt with much quicker in Canada mostly because ULP complaints were heard directly by labour boards granted authority to make binding final orders. Canadian remedies were also stronger. In some jurisdictions, a finding that an employer had unlawfully interfered with an organising campaign could lead to “remedial certification” of the union (similar to Gissel bargaining order), interim reinstatement of terminated employees pending a final decision on the merits, and access to first contract arbitration. Weiler supported these laws, but acknowledged that they may be “politically untenable” in the U.S. context.

He argued for restrictions on the right of employers to permanently replace strikers. Here again Weiler was looking to Canada where in most circumstances it is unlawful for employers to permanently replace a striking worker. And he proposed the repeal of the NLRA’s ban on employer support for employee associations, which he believed blocked potentially useful alternative forms of employee voice from emerging. Canadian labor law permits non-union employee associations even if there has been employer support.

The Updated Story: Tweaking the Wagner Model Is Not a Long Term Strategy for Revitalizing Collective Bargaining

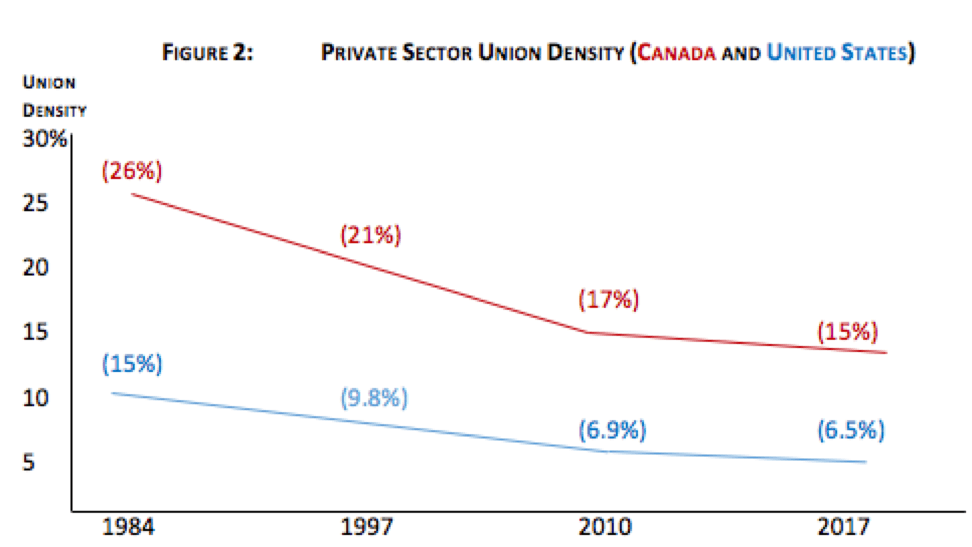

Weiler’s Canadian inspired proposals influenced labor law reform debates in the U.S. for decades. His “Promises to Keep” article is among the most cited American law review papers of all time. The failed Employee Free Choice Act included proposals pulled from Canadian labor law, including card-check certification and first contract arbitration. NLRA reform that adopted progressive elements from the “Canadian Wagner Model” would help make collective bargaining accessible to more American workers and hence union density could experience a bump. For that reason, it is worthwhile to continue to advocate for these reforms. However, it is also apparent now that the Canadian Wagner model is no panacea for all that ails U.S. labor law. Despite a more favourable legal model, Canadian private sector union density has followed a similar downwards trajectory as the U.S. since Weiler wrote his seminal comparative pieces (Figure 2).

Legal changes partly explain this decline. Most notably, while just over half of Canadian jurisdictions today use card-check certification in some form, the vast majority of Canadian workers are now governed by the instant vote model. Studies (here and here) demonstrate that union organizing success rates decline by between 9-20 percent when the law shifts from card-check to instant votes; even when votes are held within one week of the application for certification, Canadian employers have learnt to conduct effective “vote no” campaigns.

However, changes to the legal model explain only part of the decline of private sector collective bargaining in Canada as in the U.S.. The Wagner Model was designed in a different time to deal with a different economy and social reality. A new, bolder vision for the future is needed if collective bargaining is to reach the millions of workers who express a desire for collective representation but who have no effective access to it under the Wagner Model in both countries. In Canada as in the U.S., a dialogue is underway to explore what that vision might look like.

Given that Canadian collective bargaining law was built on the foundation of the Wagner Act, it is not surprising to find similar critiques and reform proposals in the two countries. Collective bargaining advocates usually have in mind an ideal version of the Canadian Wagner Model, and their proposed reforms address gaps between the prevailing model and that ideal model. The ideal model includes such familiar standards as card-check certification, stronger remedial powers to deal with ULPs, easier access to first contract arbitration, “anti-scab” legislation, and other items that facilitate organizing such as electronic membership and ballots and greater union access rights.

When it comes to proposals to strengthen the Wagner Model, Canadians advocate for much the same bundle of reforms as their U.S. colleagues.

However, occasionally, policy submissions question the continued viability of the Wagner Model, and explore alternative models that could extend the reach of collective bargaining to workers heretofore excluded, including service sector workers, homeworkers, artists, professionals, own account self-employed, “gig” workers, temp workers, and other non-standard workers. We can loosely group these proposals into two categories:

- Proposals that “move up” from workplace level bargaining to broader-based structures of collective bargaining, including sectorial, multi-employer, or industry level bargaining; and

- Proposals that “move down” from the majority, exclusive union presumption of the Wagner Model and explore alternative models of non-majority employee representation (minority unions or alternative forms of employee association) that would supplement full-fledged majority unionism where a majority is not possible or employees desire representative forms other than majority trade unionism in the Wagner model.

It would take a longer entry to explore these proposals, but it is a discussion worth having. The persistent decline in private sector union density in Canada since the 1980s suggests it is time to put to rest the idea that the Canadian Wagner Model can save collective bargaining in the U.S.. But cross-border dialogue remains crucial, not only about how to fix the Wagner Model, but about what models could replace it. The two countries share such close economic, historical, and social ties that continued labor law spillover and cross pollination seems inevitable.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 1

In today’s news and commentary, the Department of Labor proposes to roll back minimum wage and overtime protections for home care workers, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit by public defenders over a union’s Gaza statements, and Philadelphia’s largest municipal union is on strike for first time in nearly 40 years. On Monday, the U.S. […]

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]

June 27

Labor's role in Zohran Mamdani's victory; DHS funding amendment aims to expand guest worker programs; COSELL submission deadline rapidly approaching

June 26

A district judge issues a preliminary injunction blocking agencies from implementing Trump’s executive order eliminating collective bargaining for federal workers; workers organize for the reinstatement of two doctors who were put on administrative leave after union activity; and Lamont vetoes unemployment benefits for striking workers.

June 25

Some circuits show less deference to NLRB; 3d Cir. affirms return to broader concerted activity definition; changes to federal workforce excluded from One Big Beautiful Bill.