Benjamin Sachs is the Kestnbaum Professor of Labor and Industry at Harvard Law School and a leading expert in the field of labor law and labor relations. He is also faculty director of the Center for Labor and a Just Economy. Professor Sachs teaches courses in labor law, employment law, and law and social change, and his writing focuses on union organizing and unions in American politics. Prior to joining the Harvard faculty in 2008, Professor Sachs was the Joseph Goldstein Fellow at Yale Law School. From 2002-2006, he served as Assistant General Counsel of the Service Employees International Union (SEIU) in Washington, D.C. Professor Sachs graduated from Yale Law School in 1998, and served as a judicial law clerk to the Honorable Stephen Reinhardt of the United States Court of Appeals for the Ninth Circuit. His writing has appeared in the Harvard Law Review, the Yale Law Journal, the Columbia Law Review, the New York Times and elsewhere. Professor Sachs received the Yale Law School teaching award in 2007 and in 2013 received the Sacks-Freund Award for Teaching Excellence at Harvard Law School. He can be reached at [email protected].

Tascha Shahriari-Parsa is a government lawyer enforcing workers’ rights laws. He clerked on the Supreme Court of California after graduating from Harvard Law School in 2024. His writing on this blog reflects his personal views only.

Maxwell Ulin is a student at Harvard Law School.

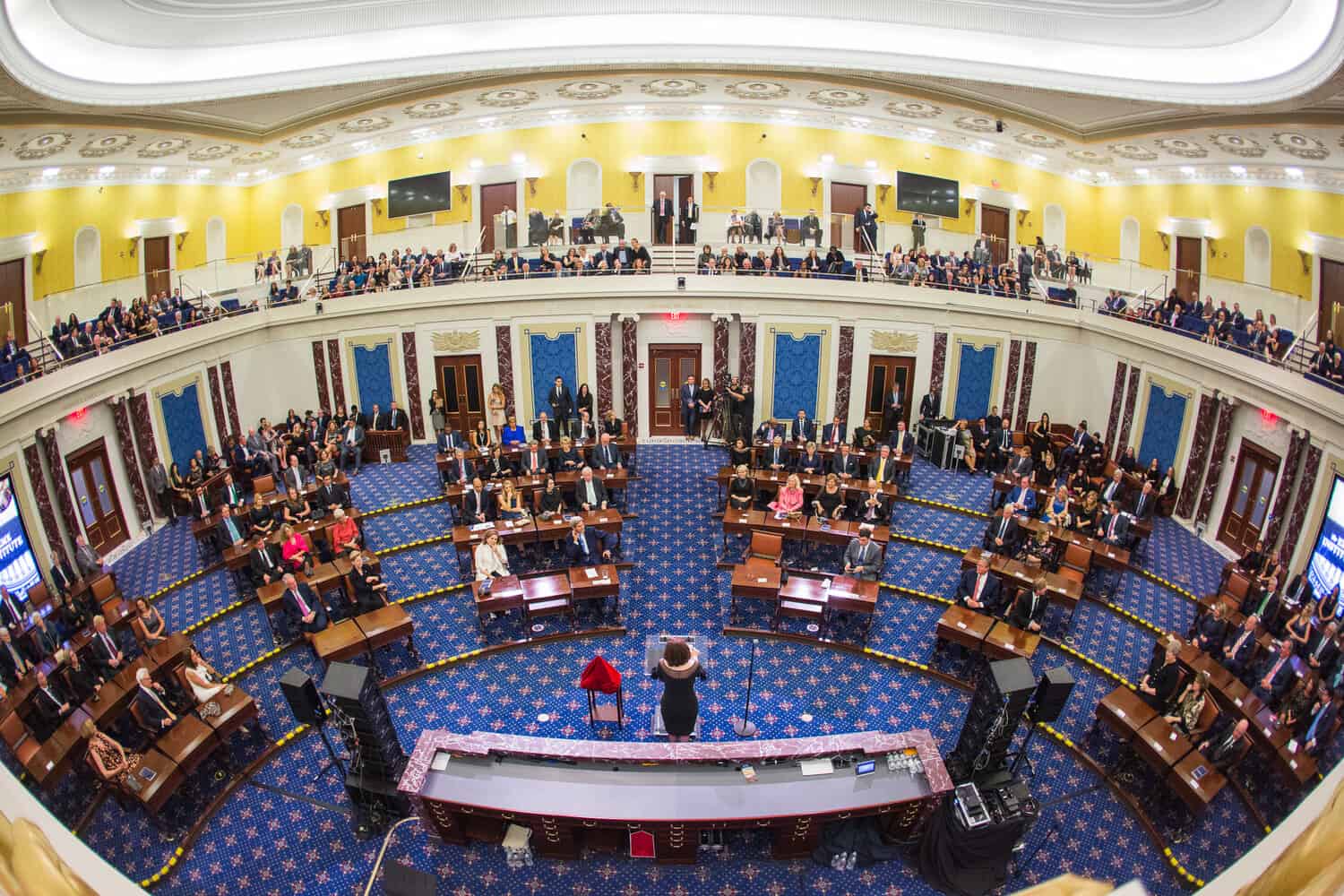

Recently, Senate Democrats have begun discussing plans to enable the National Labor Relations Board (NLRB) to levy civil monetary penalties on employers who commit unfair labor practices (ULPs) as part of their broader reconciliation bill on infrastructure. While specifics are so far lacking, the proposal is based on what House Democrats already put forward in the Protecting the Right to Organize (PRO) Act, which would establish penalties of up to $50,000 per infraction for first-time violators and up to $100,000 for certain repeat offenders.

If enacted, a new monetary penalties regime would mark the most significant, pro-worker reform of the National Labor Relations Act (NLRA) since the Act’s passage in 1935 and could significantly boost workers’ ability to address violations of their right to organize. This could, in turn, increase unions’ capacity to push for the type of broader reforms that are needed to revitalize labor law and the labor movement—reforms of the kind we called for in the Clean Slate report. Crucially, moreover, Senate precedent shows that civil penalties should survive the rules of budget reconciliation, allowing Congress to pass these provisions with even the razor-thin Senate majority Democrats currently have.

Understanding the potential impact of the proposed civil penalties requires a recognition of the truly toothless nature of the NLRA’s current remedial scheme. Since the Supreme Court has limited the NLRB to issuing compensatory relief, companies that unlawfully discharge their employees are at worst liable for what they would have otherwise paid their former workers (minus what the illegally discharged worker earns while waiting for the Board to act)—or, in the case of undocumented employees, nothing at all. When companies refuse to bargain with unions, their primary punishment is getting sent back to the bargaining table, where they can again refuse to bargain. For other violations, the remedy may consist of no more than an order to post a sign in the break room noting that the employer broke the law.

Given current remedies, the PRO Act’s civil penalties scheme would transform the nature of the NLRA remedial regime. For many employers, $50,000 fines could deter misconduct in a way that notice postings and back-pay awards never do. And in practice, it’s possible that total fines could be much more than this; as at least one labor commentator has noted, since the Supreme Court has endorsed the Board’s practice of tacking derivative 8(a)(1) charges onto 8(a)(3) and 8(a)(5) claims, almost all bargaining- and discrimination-related cases involve two alleged violations. For serial lawbreakers, the total number of charges and potential fines could quickly stack up.

Civil penalties would also meaningfully extend organizing protections to undocumented workers. While undocumented employees remain covered by the NLRA, the Supreme Court has restricted the Board from granting them backpay or reinstatement in unlawful termination cases, arguing that doing so would reward illegal employment relationships. But this principle (questionable on its own terms) does not apply to civil penalties, since those penalties are collected not by employees but by the government.

Most importantly, there is good reason to believe that the PRO Act’s civil penalties scheme can survive reconciliation’s arcane procedural rules. As one of us wrote in February, laws passed through budget reconciliation generally must meet six criteria under the so-called “Byrd Rule.” Specifically, a provision can only pass through reconciliation if: (1) it alters government revenues or spending; (2) its fiscal impact complies with the instructions of the initial budget resolution; (3) it was inserted by the appropriate congressional committee; (4) its budgetary impact is not “merely incidental” to the non-budgetary aspects of the provision; (5) it does not increase the deficit beyond the allotted budgetary window; and (6) it does not affect Social Security. Typically, the fourth prong—the “merely incidental” test—is the trickiest to meet, as Bernie Sanders’ failed attempt to raise the minimum wage through reconciliation showed. Whether a provision passes the Byrd Rule is left to the discretion of the Senate parliamentarian, who relies heavily on past reconciliation precedent to render case-by-case rulings.

Fortunately, civil penalties have passed time and again through reconciliation. Since the Byrd Rule’s adoption, legislators from both parties have included similar fines in reconciliation bills passed in 1985, 1986, 1987, 1989, 1990, 1993, 1995, and 2005. In doing so, Congress has imposed civil monetary penalties on a wide range of private conduct, including bridge obstruction, foreign tobacco purchases, maritime shipping infractions, tax fraud, Medicaid non-compliance, and ERISA, OSHA, and FLSA violations, to name a few. Such a rich legislative precedent indicates that the fiscal impact of NLRA civil penalties ought not to be considered “merely incidental” within the meaning of the Byrd Rule. Given that many past civil penalties were imposed on previously unregulated conduct, it may well be possible to impose fines even for things such as captive audience meetings not currently proscribed under federal labor law.

As for the other Byrd-Rule requirements, the measure’s qualifications are pretty straightforward. By collecting government revenues, civil penalties would have a direct, positive impact on the budget, as measured by both the Congressional Budget Office and outside advocates. Since the measure clearly has no impact on the Social Security program, the only outstanding requirements are that Democrats follow the proper procedural rules in including the measure. All of this means that a key provision of the PRO Act could pass Congress under reconciliation—bypassing the Senate filibuster with a simple majority vote.

To be clear, we should not be satisfied with new penalties. For one thing, companies like Amazon and McDonalds might well decide to pay even the heightened fees under consideration rather than respect their workers’ right to organize. Moreover, labor law is fundamentally broken; what is really needed is a fundamental rewrite of the statute, as outlined in the Clean Slate report. But that doesn’t mean we shouldn’t also push for other victories that can make it easier for many workers to build power in the short-term. After nearly 80 years of labor law’s uninterrupted erosion, Congress’s enactment of enhanced penalties through reconciliation would be historic and deserves our support.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

March 13

Republican Senators urge changes on OSHA heat standard; OpenAI and building trades announce partnership on data center construction; forced labor investigations could lead to new tariffs

March 12

EPA terminates contract with second-largest union; Florida advances bill restricting public sector unions; Trump administration seeks Supreme Court assistance in TPS termination.

March 11

The partial government shutdown results in TSA agents losing their first full paycheck; the Fifth Circuit upholds the certification of a class of former United Airline workers who were placed on unpaid leave for declining to receive the COVID-19 vaccine for religious reasons during the pandemic; and an academic group files a lawsuit against the State Department over a policy that revokes and denies visas to noncitizens for their work in fact-checking and content moderation.

March 10

Court rules Kari Lake unlawfully led USAGM, voiding mass layoffs; Florida Senate passes bill tightening union recertification rules; Fifth Circuit revives whistleblower suit against Lockheed Martin.

March 9

6th Circuit rejects Cemex, Board may overrule precedents with two members.

March 8

In today’s news and commentary, a weak jobs report, the NIH decides it will no longer recognize a research fellows’ union, and WNBA contract talks continue to stall as season approaches. On Friday, the Labor Department reported that employers cut 92,000 jobs in February while the unemployment rate rose slightly to 4.4 percent. A loss […]