Chinmay G. Pandit is the Digital Director of OnLabor and a student at Harvard Law School.

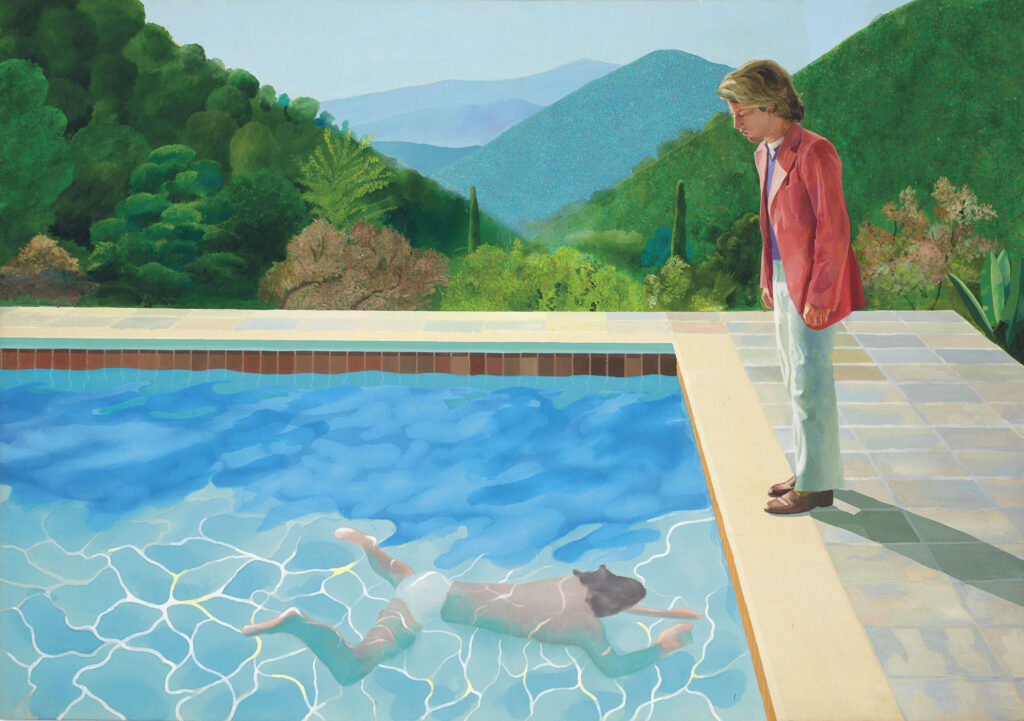

50 years ago, world-renowned artist David Hockney sold his painting, “Portrait of an Artist (Pool With Two Figures),” for an inflation-adjusted price of $124,000. In 2018, that same painting re-sold for a record-breaking $90.3 million; unfortunately for Hockney, he did not receive a single penny from the re-sale. When asked about it, Hockney acknowledged that the art industry had already burned him multiple times: just six months after he first sold this same painting in 1972, the buyer flipped it for $344,000.

Hockney’s story is standard practice in the art industry. Most artists benefit only from the primary market, where their works are sold for the first time. Because artists often have limited financial means, they are typically compelled to sell their art prematurely, offloading pieces at a relatively low price before the artists’ reputations fully form. In turn, as their artwork’s value appreciates over time, the majority of profits are generated on the secondary market where the painting is re-sold, changing hands from one owner to another.

Thus, instead of internalizing the benefits of their own work, artists are forced to watch middlemen dealers — who buy art for a myriad of reasons including aesthetic appeal and investment potential — cash in on sizeable paydays by simply holding onto a painting and waiting for its value to increase. As artist Frank Stella puts it, the “benefits from the appreciation of artworks accrue entirely to others, despite the artist’s essential and ongoing work in . . . building the value of their works.”

The asymmetric profit distribution, artists argue, reflects the current system’s moral defects and economic disincentives, failing to fulfill a fundamental principle that artists should benefit from the increasing value of their labor’s output. Those who support the artists now believe that reform is necessary to provide fair compensation for artists’ labor. To lead the charge, nascent technology companies are reinventing a solution that policymakers have for years struggled to implement: re-sale royalties. But whether their strategy will sufficiently address artists’ concerns remains to be seen.

Re-Sale Royalties

A royalty is a legally binding payment that compensates an asset’s original owner on an ongoing basis for future use of that asset. Royalties can be tied to either reproductions or re-sales of the original work. The music and entertainment industries have historically opted for reproduction-based royalties that pay artists a fixed revenue every time a duplicate of their work is shared. Movie producers and musicians, for example, own royalty contracts via producer residuals and soundtrack licenses that allow them to benefit each time their movie or song is played on a platform like Netflix or Spotify. But the visual art industry has been less successful at implementing a reproduction-based royalty system, in large part because of the industry’s inherent “premium on uniqueness,” meaning that consumers of visual art place a significant value premium on the original artwork compared to copies.

However, re-sale royalties — which are based on future re-sales of the artist’s original work (rather than sales of copies) — may offer a more viable, fair, and lucrative path for artists to share in their paintings’ upside potential. European soccer teams, as an example, utilize a re-sale royalty-like model through sell-on clauses when trading soccer players. Teams typically trade players in exchange for monetary payments, known as “transfer fees”. Similar to the art industry, small, low-budget soccer teams are often forced to trade away talented, though not-yet-famous players prematurely for a modest transfer fee, only to see that same player command a significantly higher re-sale transfer fee when they become world-famous a few years later. The sell-on clause allows those low-budget teams — who invest resources in identifying and developing young players — to receive a certain percentage of future transfer fees associated with their former player, if he is transferred to a third team down the line. Sell-on clauses are negotiable and allow small teams to benefit over time from their initial efforts, providing a blueprint to help visual artists do the same thing.

Fairchain

Fairchain, a budding technology start-up, is adapting the European soccer-like re-sale royalty system to the art industry, leveraging blockchain technology to help artists retain a share of future profits from their work. Fairchain first executes the initial art sale via a smart contract that remains permanently connected to the artwork. Unlike written contracts, which can be difficult to track and enforce in an international (and often private) art market, Fairchain’s proprietary technology pairs with the artwork regardless of its location. Thereafter, bona fide re-sales are publicly registered to the blockchain, constantly ensuring that the artwork is authenticated and the purchaser is verified. Upon recording the re-sale, Fairchain automatically transmits the royalty back to the original artist, allowing seamless and perpetual participation in the artwork’s secondary market sale proceeds.

Importantly, Fairchain also allows artists to select their own royalty percentage. Artists can therefore adjust their compensation structure based on their needs, allocating between initial sales price and future re-sale royalty percentage. Artists who firmly believe in their artwork’s future appreciation can opt for a lower initial price in exchange for a higher percentage of future revenue. Alternatively, artists who prefer more cash upfront may set a larger initial payment, sacrificing some future income. The intertemporal pricing flexibility gives artists a valuable negotiating tool when first placing their artwork for sale.

Is Fairchain Enough?

Despite its benefits, Fairchain may still fall short of fully remedying the underlying bargaining power imbalance between artists and buyers. Put simply, buyers can always choose to not purchase a Fairchain-mediated art piece, thereby avoiding paying a re-sale royalty. And since visual art purchasers are often high-net-worth individuals wealthier than the artists, buyers typically hold a disproportionate amount of bargaining power to dictate the terms and medium of art sales. If buyers conclude that the costs of re-sale royalties outweigh the security benefits of Fairchain, artists are powerless to demand a royalty.

To address the disparity, legislation may be required to enforce mandatory visual art re-sale royalties, cementing artists’ legal right — not just ability — to reap the long-term benefits of their creations. Internationally, re-sale royalty laws have been implemented to varying degrees of success. France developed the earliest mandated re-sale royalty, guaranteeing a remittance for 70 years past the artist’s death. In the U.S., however, no such re-sale royalty legislation presently exists, though proposals have been evaluated sporadically for decades. In 2015, Congress seriously contemplated (but failed to pass) a federal “American Royalties Too Act” that would have mandated a 5% royalty (capped at $35,000) on art sales over $5,000. Though largely supportive of the bill’s moral thrust, critics cited concerns about its lack of enforceability in highly opaque private art markets; others found the flat 5% royalty to be restrictive for artists seeking to modify the percentage between pieces.

Fairchain’s innovations help ameliorate both concerns. Thus, going forward, efforts to impose a federally mandated re-sale royalty for visual artists should aim to integrate the advantages of Fairchain’s technology to promote a flexible, secure, and fair art market. While legislation can substantially alter artists’ bargaining power, Fairchain’s technology can provide the requisite security, enforceability, and automation to make re-sale royalty legislation more effective. Together, Congress and Fairchain can help artists earn (and maybe even feel like) a life-long royalty.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

March 12

EPA terminates contract with second-largest union; Florida advances bill restricting public sector unions; Trump administration seeks Supreme Court assistance in TPS termination.

March 11

The partial government shutdown results in TSA agents losing their first full paycheck; the Fifth Circuit upholds the certification of a class of former United Airline workers who were placed on unpaid leave for declining to receive the COVID-19 vaccine for religious reasons during the pandemic; and an academic group files a lawsuit against the State Department over a policy that revokes and denies visas to noncitizens for their work in fact-checking and content moderation.

March 10

Court rules Kari Lake unlawfully led USAGM, voiding mass layoffs; Florida Senate passes bill tightening union recertification rules; Fifth Circuit revives whistleblower suit against Lockheed Martin.

March 9

6th Circuit rejects Cemex, Board may overrule precedents with two members.

March 8

In today’s news and commentary, a weak jobs report, the NIH decides it will no longer recognize a research fellows’ union, and WNBA contract talks continue to stall as season approaches. On Friday, the Labor Department reported that employers cut 92,000 jobs in February while the unemployment rate rose slightly to 4.4 percent. A loss […]

March 6

The Harvard Graduate Students Union announces a strike authorization vote.