Mike Klain is a student at Harvard Law School and a member of the Labor and Employment Lab.

In a recent poll, two-thirds of respondents agreed with the statement “inflation is a very big concern for me.” These concerns are not without merit: the Consumer Price Index, which tracks the weighted-average prices of consumer goods and services, showed a 6.2% annual increase in October, the largest rate of increase in thirty years. The increase in consumer prices has set off a firestorm of debates about why it’s happening, whether it’s transitory or permanent, and what policymakers should do in response. As Congressional Democrats debate the Build Back Better Act, which contains a significant provision from the labor-friendly PRO Act, some members are citing concerns about inflation as a justification for changing or abandoning the bill. The outcomes of these debates will therefore have a tremendous impact on the outlook for workers in the years to come.

Particularly important for workers is the question of whether wage increases – which tend to be sticky – rather than temporary supply chain disruptions are driving the increase in prices. Wages increased at their fastest rate since 2001 in the third quarter, and wages are rising at the fastest annual rate since 2004. The fact that wages are rising as the unemployment rate continues to fall, recently falling below 5% for the first time since the beginning of the pandemic but still above the pre-pandemic baseline of 3.5%, has sparked renewed interest in the once-canonical Phillips Curve. Yet those looking to the Phillips Curve to find answers for rising prices are mistaken: rolling supply shocks from global pandemic waves and a dramatic re-balancing of consumer spending from services to goods are the more likely culprits.

History of The Phillips Curve

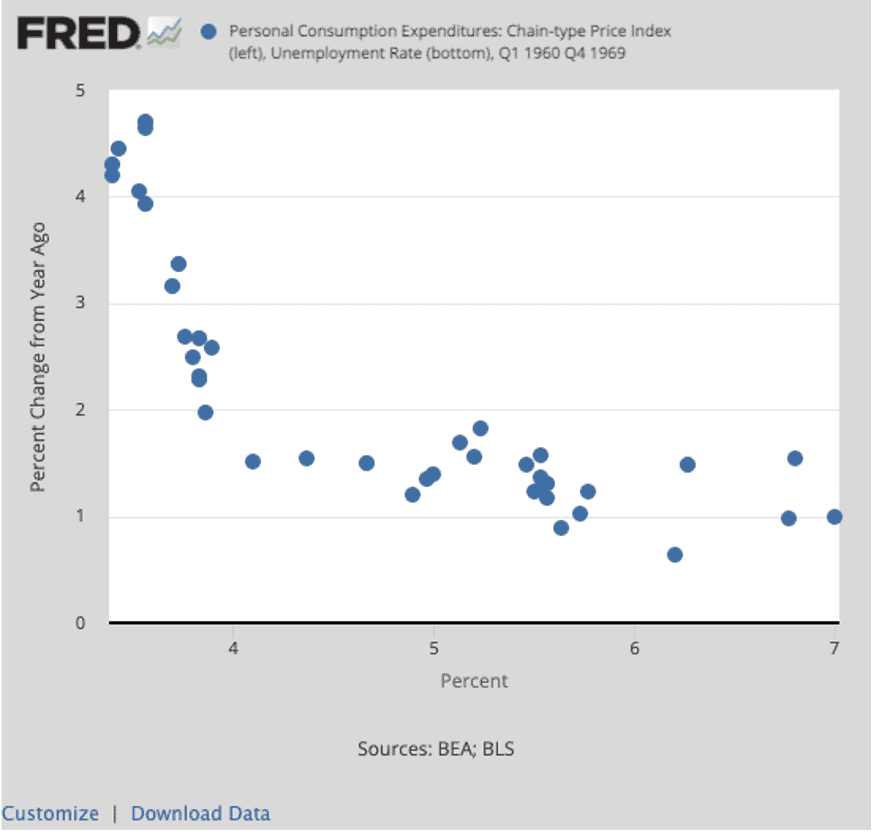

The Phillips Curve is an economic theory pioneered by William Phillips in 1958, which suggests that there is an inverse relationship between unemployment and inflation. According to the theory, when unemployment is low, demand for workers is high, meaning workers can bargain for higher wages. As a result of increasing labor costs, firms will have to raise prices for consumers, driving inflation. This theory appeared to accurately predict the relationship between unemployment and inflation in the 1960’s:

Change in Consumer Price Index (Y-axis) vs. Unemployment Rate (X-axis), 1960-1969

Because of the theory’s predictive power and intuitive nature, the Phillips Curve quickly became a staple of monetary and fiscal policy. Beginning in the 1970s, however, as supply shocks to crucial commodities like oil drove both inflation and unemployment up, the relationship between the variables appeared to break down:

The Phillips Curve Today

In the years leading up to the pandemic, economists began to ask deeper questions about whether the Phillips Curve had permanently flattened. In Q4 2019, the Congressional Budget Office estimated that the Non-Cyclical Rate of Unemployment, the long-run rate of unemployment we would expect to observe absent short-run fluctuations in aggregate demand, was 4.5%; the actual Unemployment Rate in December 2019, meanwhile, was 3.6%. Although Phillips Curve theory would predict that the tight labor market should have caused inflation to accelerate, prices remained stagnant; the annual rate of price growth in December 2019 was just 2.3%. Economists assessed whether the Phillips Curve was dead or merely dormant, and whether policymakers should change their approach as a result. Just as this debate was accelerating, however, the COVID-19 pandemic introduced an unprecedented disruption to the global economy, sending the Unemployment Rate to 14.8% in April 2020.

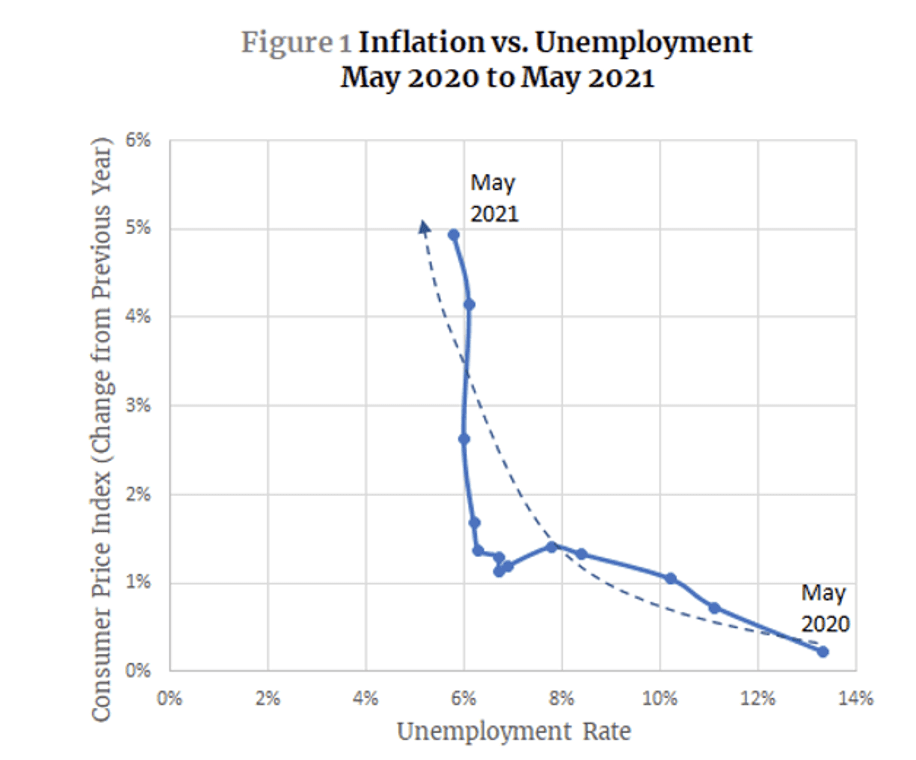

Seventeen months later, the labor market appears to have tightened again, with the Unemployment Rate back down to 4.8%, the number of people quitting reaching an all-time high, and the number of unemployed people per job opening matching its record low level from before the pandemic. The combination of a tight labor market, rising wages, and rising prices has raised questions about whether the COVID crisis awoke the sleeping Phillips Curve, particularly in sectors like meatpacking where labor shortages are particularly acute:

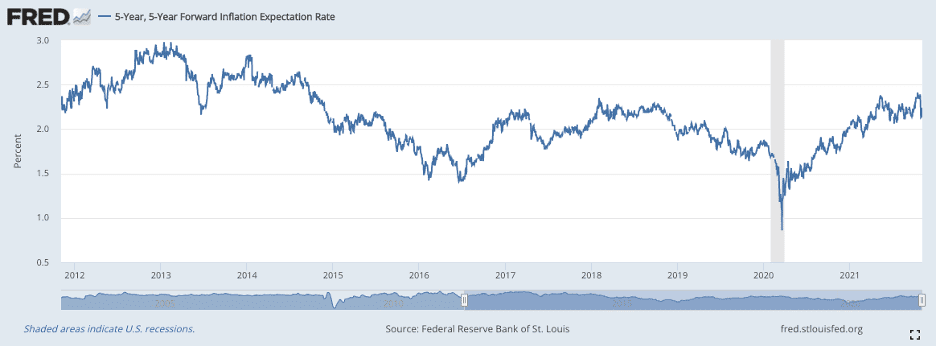

The answer may come down to inflation expectations. In the late 1960s and early 1970s, Friedman and Phelps posited that changing expectations of future inflation could, rather than merely causing movements along the Phillips Curve, actually shift the curve in either direction. Operationally, high and variable inflation leads to elevated unemployment by distorting relative prices – thereby shifting behavior away from optimal market equilibriums, creating a “bullwhip effect,” and increasing monetary policy uncertainty. Additionally, rising inflation expectations can cause a “wage-price spiral,” during which workers demand their pay increase because of rising prices, necessitating that companies pass along rising input costs to consumers. This theory of expectations-driven inflation would explain why, even as unemployment fell below the Natural Rate of Unemployment, anchored inflation expectations kept actual inflation in check.

An economist from the Niskanen Center, Ed Dolan, argues that the Phillips Curve could therefore return if inflation expectations become unanchored. In some ways then, the “transitory” debate becomes self-reinforcing: if advocates of transitory inflation are able to make a convincing argument, inflation expectations themselves will remain low. So far, it appears that those arguing that inflation is transitory are being heard:

Economists Jorgensen and Lansing, meanwhile, argue that the Unemployment Rate is the wrong variable to plot on the x-axis. According to Jorgensen and Lansing, economic output, as measured by the gap between short-run output and long-run potential, better explains upward pressure on prices. Under this theory, there are two potential paths back to a lower level of inflation: a decrease in short-run output, or an increase in long-run economic potential through investments in productive capacity.

How Policymakers Could Respond

First, policymakers should not mistake short-run economic challenges for policy or political mistakes. On the policy front, policymakers should, rather than caving to pressure and reducing short-run output, remain accommodative to spark investment. Current Treasury Secretary Yellen said it best in 2016: “[S]trong demand could potentially yield significant productivity gains by, among other things, prompting higher levels of research and development spending and increasing the incentives to start new, innovative businesses.” There is already evidence that capital expenditures and research and development spending levels are rising.

On the political front: the 2021 election results make one lesson abundantly clear – the problems stemming from doing “too much” (at $1.9 trillion, ARP clearly overshot the Output Gap caused by the pandemic) are far more tolerable for voters than the problems stemming from doing “too little” (at $787 billion, ARRA fell below estimates of the Output Gap from the financial crisis). While Virginia and New Jersey shifted 23.6% and 19.2% to the right respectively in 2009, they shifted just 12.6% and 13.6% to the right respectively in 2021, and the newly-elected President’s party actually won one of these two elections for the first time since 1981.

Additionally, policymakers must find a way to balance recognizing the real pain caused by rising prices with clear and forceful pushback against misplaced outrage designed to undermine worker power. The potential to pass a significant portion of the PRO Act is not all that’s at stake. Voters blame President Biden’s policies for rising prices, and might be less receptive to similar policies in the future; a majority of voters now think the expanded Child Tax Credit, which has significantly cut child poverty, should not be made permanent. Federal Reserve Chair Jerome Powell, whose emphasis on achieving a rapid and racially-equitable labor market recovery has stunned analysts, is under attack from unlikely allies Elizabeth Warren, Larry Summers, and Joe Manchin as he faces the prospect of confirmation for a second term. Rather than accept a narrative that might hurt workers in the long-turn, policymakers should go on the offensive about how their interventions have helped support the most vulnerable.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

August 5

In today’s news and commentary, a pension fund wins at the Eleventh Circuit, casino unionization in Las Vegas, and DOL’s work-from-home policy changes. A pension fund for unionized retail and grocery workers won an Eleventh Circuit appeal against Perfection Bakeries, which claimed it was overcharged nearly $2 million in federal withdrawal liability. The bakery argued the […]

August 4

Trump fires head of BLS; Boeing workers authorize strike.

August 3

In today’s news and commentary, a federal court lifts an injunction on the Trump Administration’s plan to eliminate bargaining rights for federal workers, and trash collectors strike against Republic Services in Massachusetts.

August 1

The Michigan Supreme Court grants heightened judicial scrutiny over employment contracts that shorten the limitations period for filing civil rights claims; the California Labor Commission gains new enforcement power over tip theft; and a new Florida law further empowers employers issuing noncompete agreements.

July 31

EEOC sued over trans rights enforcement; railroad union opposes railroad merger; suits against NLRB slow down.

July 30

In today’s news and commentary, the First Circuit will hear oral arguments on the Department of Homeland Security’s (DHS) revocation of parole grants for thousands of migrants; United Airlines’ flight attendants vote against a new labor contract; and the AFL-CIO files a complaint against a Trump Administrative Executive Order that strips the collective bargaining rights of the vast majority of federal workers.