Chinmay G. Pandit is the Digital Director of OnLabor and a student at Harvard Law School.

In a world overcome by the cryptocurrency frenzy, large public pension funds — historically known for their ultra-safe investing style — have just entered the chat. The Houston Firefighters’ Relief and Retirement Fund, a pension fund for, as the name suggests, Houston’s firefighters, made news last October as the first American public pension plan to voyage into the cryptocurrency commotion, purchasing $25 million worth of Bitcoin and Ether in the hopes of cashing in on a big-time return.

While HFRRF’s purchase reflects a mere droplet compared to the $5.5 billion of total assets that the pension oversees, the move nevertheless signals another step in a relatively recent transition to high-risk, high-reward investments for these organizations. And unless regulators act quick, things could get messy.

What are Pension Funds?

The premise underlying public pension funds is fairly straightforward: employers promise to pay a fixed amount of income to employees once they retire, the benefits of which are protected by law, and while working, the employee contributes a portion of their salary to their retirement account, which is managed and invested by a pension fund on the employees’ behalf.

Years later, when an employee retires, pension funds use (a) employee contributions plus (b) additional revenue from investing to provide the retiree with the initially promised amount. In all, today’s public pensions — which cover public employees ranging from teachers to firefighters — encompass 15 million working members and oversee $14.7 trillion in total assets, paying $323 billion in annual retirement income to 11 million retirees.

Pension Problem

Unfortunately, over the past decade, public pension funds have struggled to produce the requisite income promised to employees. States experienced a $1.25 trillion pension funding gap in 2019, meaning they owed over a trillion more dollars to retirees than they could afford.

States have historically taken on debt to cover immediate shortfalls, but borrowing merely delays the deficits, making it an unsustainable solution. Instead, municipalities can pull longer-term levers to address the funding gap, such as raising taxes, reallocating funds across budgets, or increasing employee contributions. However, each of these options is politically unpopular, dissuading policymakers from selecting them. Thus, to avoid perturbing voters, public pension funds have explored a fourth option: investing in assets that generate higher returns, albeit with higher risk.

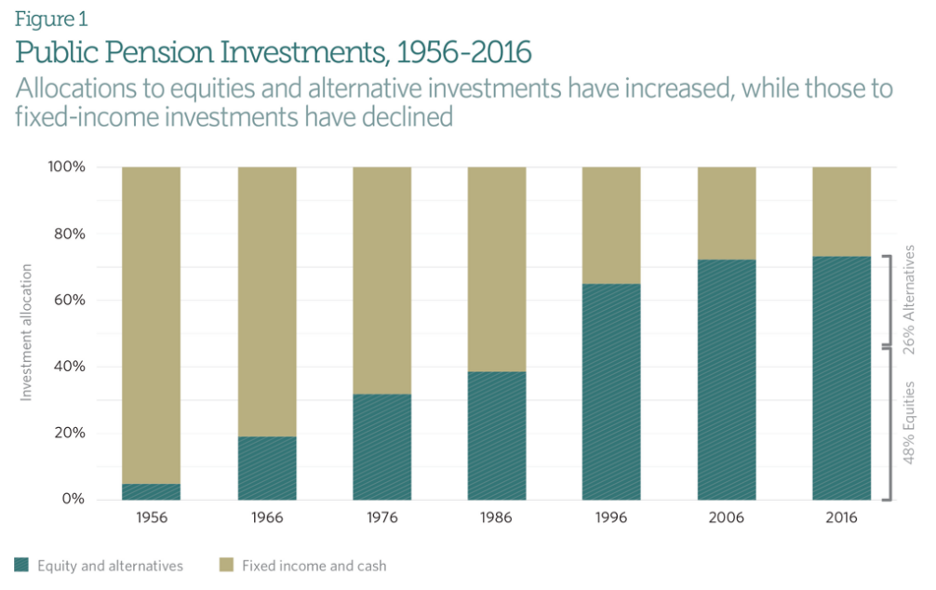

Traditionally, pension funds — regarded as the most “conservative, risk-averse investors” — have allocated approximately 70% of their portfolios to hyper-safe government bonds, with the remaining 30% allocated to traditional stocks or kept as cash (see Figure 1, from the Pew Charitable Trusts). This strategy was viable in the mid-1970s when government bonds yielded 10% annually, meaning that a $100 billion pension could generate $10 billion of risk-free profit each year, thereby meeting retiree obligations more easily.

But since the 2008 financial crisis, interest rates have been slashed to 0.1% today, just one one-hundredth of that from 50 years ago. Meanwhile, state pension retirement obligations have nearly doubled in the past 10 years. As a result, pension funds have struggled to keep up with their growing commitments to retirees, spurring a desperate search for higher-yielding investments, risky or otherwise.

The Search for Yield

Over the past two decades, hedge funds and private equity firms (collectively called “alternatives”) have captivated the hearts of public pension plans, pledging to generate substantially higher returns in exchange for fees. In 2001, alternatives comprised just 8% of public pension fund portfolios. That number has climbed to 26% today as alternatives have posted strong recent profits.

Yet, robust gains come with significant risk. Namely, hedge funds and private equity firms charge exorbitant fees, are subject to fewer regulations, and often require multiyear capital commitments, meaning that pensions cannot readily access their money in case of emergency. Additionally, many alternatives adhere to inherently risky strategies, such as buying bankrupt companies, which can return large profits in good years, but severe losses in down years.

Regrettably for pension funds, though, few choices exist if they want to fully cover their retiree obligations. Some pensions, like HFRRF, are beginning to explore the world of digital currencies, attracted by its instantaneous, low-fee structure. And, more importantly, the overall cryptocurrency market has exploded in value over the past ten years, with Bitcoin rising from a fraction of a penny to over $40,000 today, which helps investors rationalize the currency’s significant volatility. Given this potentially lucrative opportunity, some experts anticipate that large pension funds will invest as much as one-fifth of their total assets in the cryptocurrency space within the next five years, a move that would represent an unprecedentedly rapid overhaul of the once highly conservative pension plan portfolio.

Risk and the Regulatory Landscape

In anticipation for the increased role that cryptocurrency is expected to play in pension fund investing, regulators must work quickly to build out a workable governing framework to protect public employees and their retirement savings. Despite its headline-grabbing upside potential, the underdeveloped cryptocurrency market is still fraught with cases of fraud and theft as well as alarming volatility (Bitcoin has dropped 27% since HFRRF’s announcement in October), and could thus result in devastating outcomes for public employees unless proper guardrails are put in place.

Currently, state and local governments serve as the primary managers of public pension funds; however, the Employee Retirement Income Security Act, which provides the central regulatory scheme for private pensions, exerts considerable influence on public pension plan standards, offering an important source of protections for public retirees.

As of now, cryptocurrencies are not banned as a retirement-related investment option by ERISA, though they have not been explicitly condoned either. ERISA does impose fiduciary duties of prudence and diversification on plan managers to appropriately assess investment risks and benefits and to avoid overexposure to a single asset, like cryptocurrency. Additionally, although ERISA presently permits most types of investments, the law prohibits investing in art, antiques, gems, coins, and alcoholic beverages, considering these “collectibles” ostensibly too risky and uniquely difficult to value. Whereas stock prices are always accessible, high-end art and fine wine can only be valued by occasional auctions or imperfect appraisers, rendering collectibles vulnerable to blind-siding drops in value.

The question is then whether cryptocurrencies are so similar to collectibles that they too must be banned from pension fund portfolios. On the one hand, some argue that cryptocurrencies are just as risky (if not more) as real paintings, since cryptocurrency prices endure frequent, acute swings and the nuances of crypto investing are difficult to comprehend. On the other hand, crypto prices are transparent and instantly verifiable since the currencies are traded in real time, just like stocks. Therefore, account managers holding crypto can constantly track their investment’s value to make educated transaction decisions, a feature missing from banned collectibles.

If digital currencies are ultimately permitted within pension fund portfolios, then at minimum, regulators must consider applying uniform limits on the amount of cryptocurrency each pension fund may hold to avoid overly risky portfolios. Additionally, policymakers ought to implement annual cryptocurrency-specific stress testing obligations to demonstrate how cryptocurrency and other risky alternative holdings may impact future retirees under various scenarios. And of course, strict transparency requirements are critical to promote clear information-sharing with constituents.

Until then, though, HFRRF and other pension funds will have to hope that cryptocurrencies rally back from their recent nosedive — that is one fire that HFRRF’s employees will not be able to put out by themselves.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

July 4

The DOL scraps a Biden-era proposed rule to end subminimum wages for disabled workers; millions will lose access to Medicaid and SNAP due to new proof of work requirements; and states step up in the noncompete policy space.

July 3

California compromises with unions on housing; 11th Circuit rules against transgender teacher; Harvard removes hundreds from grad student union.

July 2

Block, Nanda, and Nayak argue that the NLRA is under attack, harming democracy; the EEOC files a motion to dismiss a lawsuit brought by former EEOC Commissioner Jocelyn Samuels; and SEIU Local 1000 strikes an agreement with the State of California to delay the state's return-to-office executive order for state workers.

July 1

In today’s news and commentary, the Department of Labor proposes to roll back minimum wage and overtime protections for home care workers, a federal judge dismissed a lawsuit by public defenders over a union’s Gaza statements, and Philadelphia’s largest municipal union is on strike for first time in nearly 40 years. On Monday, the U.S. […]

June 30

Antidiscrimination scholars question McDonnell Douglas, George Washington University Hospital bargained in bad faith, and NY regulators defend LPA dispensary law.

June 29

In today’s news and commentary, Trump v. CASA restricts nationwide injunctions, a preliminary injunction continues to stop DOL from shutting down Job Corps, and the minimum wage is set to rise in multiple cities and states. On Friday, the Supreme Court held in Trump v. CASA that universal injunctions “likely exceed the equitable authority that […]