Dr. David Doorey is a Professor of Labor and Employment Law at York University in Toronto.

In early July, the British Columbia Labour Relations Board (BCLRB) certified UFCW-Canada as the bargaining representative for over 500 UBER drivers in the province’s capital city of Victoria. A few days later, the BCLRB issued another decision that certified the union Unifor (formerly the Canadian Auto Workers) for a bargaining unit of hundreds of employees employed at an Amazon distribution centre in suburban Vancouver. These victories are noteworthy not only because of the anti-union corporations involved, but also because the unions were aided by several simple legal rules found in the B.C. Labour Relations Code. (In Canada, labor relations falls primarily within provincial rather than federal jurisdiction.)

UBER, Card-Check, and Dependent Contractor Bargaining Units

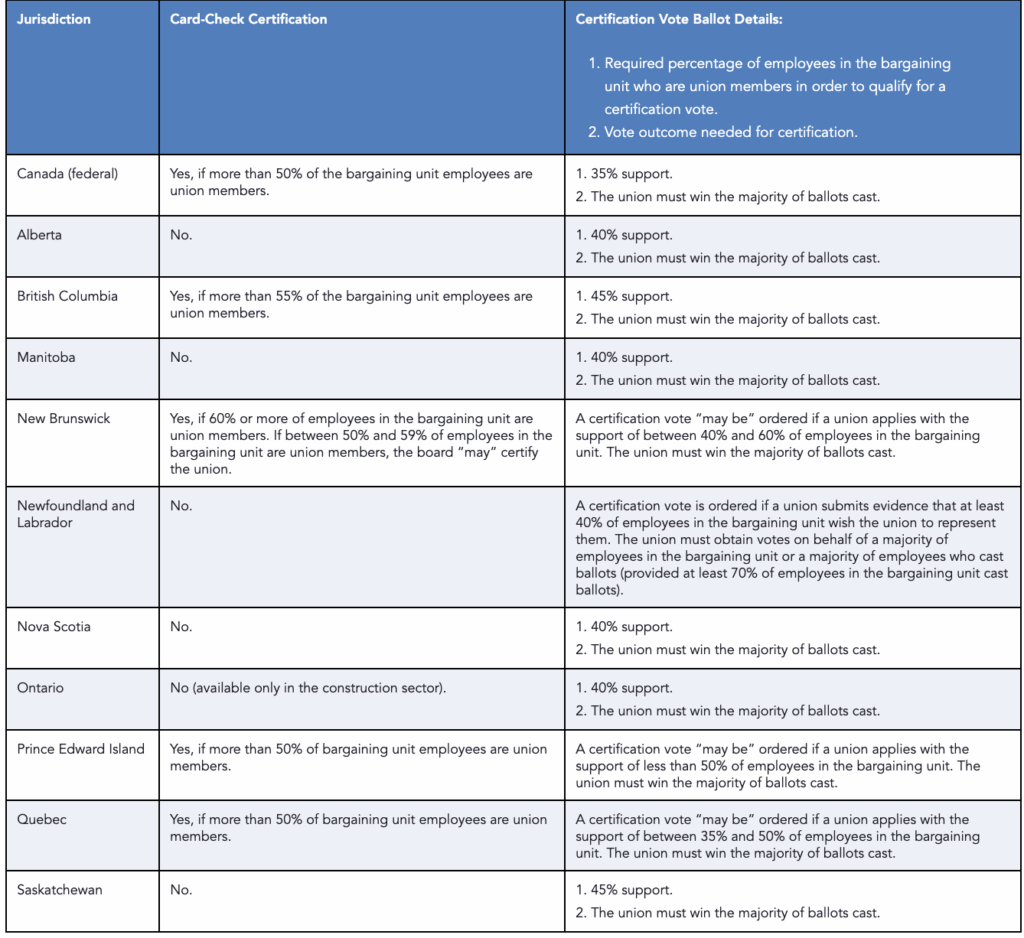

UFCW won bargaining rights with barely a fight by Uber, benefitting from two legal rules found in the B.C. labor legislation. The first rule is card-check certification. British Columbia is one of five (of 11) Canadian jurisdictions that permits labor boards to certify a union based on union membership evidence representing a majority of bargaining unit employees (see the chart below from my book The Law of Work). UFCW was certified after the BCLRB confirmed that the union had submitted membership evidence representing greater than 55 percent of drivers in the bargaining unit, which is the required threshold in the B.C. Labour Relations Code. The absence of a requirement for a vote after a union has already collected and submitted union membership cards on behalf of at least 55 percent of workers reduces the sort of pitched battles that are so common in the NRLA mandatory certification vote model.

The second legal rule that benefited UFCW requires that “dependent contractors” be treated as “employees” for the purposes of collective bargaining. Canadian labor relations legislation typically defines “employee” as “including a dependent contractor” and then defines dependent contractor broadly to include workers who, regardless of whether they meet the legal tests for “employment” status, stand in a position of economic dependence such that they “more closely resemble an employee than an independent contractor” (see Section 1 of the B.C. Code). While the question of whether platform workers such as Uber drivers meet the legal test of “employment” remains a live question in Canada, there is little doubt that they are “dependent contractors” and therefore covered by collective bargaining legislation, as I explained in this earlier post.

Confronted with this legal reality, UBER did not even argue that its drivers were independent contractors in Victoria. While there was some normal back and forth about which drivers should be included in the bargaining unit for the purposes of the count, the status of the drivers was not raised as an issue. UFCW asserted that the drivers were dependent contractors, Uber did not challenge this, and Section 28 of the B.C. Code directs the BCLRB to certify a unit of dependent contractors if that is the unit sought by the union. Therefore, the BCLRB certified a bargaining unit of UBER drivers without a vote, making this the first unionized unit of UBER drivers in North America.

Amazon and Remedial Certification

The Amazon certification story is quite different. In contrast to the relatively muted response of UBER to the organizing campaign, Amazon stayed truer to its reputation as a global union-busting rogue employer. Upon learning of Unifor’s campaign, Amazon put in motion a two-pronged resistance strategy. Firstly, management personnel conspired to inflate the number of employees in the bargaining unit in the hope this would ultimately leave the union short of majority support. For an interesting read, check out the panicked communications between managers about how to justify 50-100 immediate new hirers (which begins around paragraph 50 of the BCLRB’s decision.)

Secondly, Amazon “bombarded” (the BCLRB’s word) the employees with anti-collective bargaining propaganda in the form of continuous posters, leaflets, videos, phone calls, emails, and group and individual conversations at work designed to discourage employees from supporting Unifor. Upon learning of the campaign, the company dispatched its “Field Team” comprised of senior management personnel from across North America to help quash the union drive. While labor laws permit employers in Canada to state facts and non-threatening opinions about unionization, the BCLRB ruled that Amazon unlawfully swamped employees with the overwhelming message that collective bargaining is not in their interests, including making “implied threats that employees may lose benefits they currently have” if the union was certified (para. 153).

Having ruled that Amazon acted unlawfully, the BCLRB was then tasked with ordering a remedy and it is at this point that another important but simple labor law came into play. In B.C., as in most other Canadian jurisdictions, labor relations legislation grants the labor board authority to certify a union as a remedy for serious employer unfair labor practices that cast a cloud over the ability of workers to freely choose whether they want collective bargaining (see Section 14(4.1) of the Code). The BCLRB ruled that remedial certification is warranted in this case (para. 163):

Given Amazon’s lengthy and pervasive anti-union campaign, coupled with numerous additional unnecessary and artificial hires, I find Amazon’s conduct is serious such that it would be difficult to ascertain the true wishes of the employees through any other means.

Remedial certification is rarely ordered in Canada — the Amazon order is just the 14th remedial certification granted by the BCLRB since 2014 — but it serves as a significant disincentive for companies to break the law during organizing campaigns. The first unionized Walmart store in North America also resulted from remedial certification after the company engaged in conduct very similar to Amazon at a store in Ontario in the 1990s.

Simple, But Effective Labor Law

Card-check certification, remedial certification, and recognition of “dependent contractors” as a category of employee are not new developments in Canadian labor law. They date back decades and are hardly revolutionary. These rules represent simple but effective labor policy that is designed to streamline and improve access to collective bargaining for workers who want it, while discouraging employers from engaging in unlawful attempts to undermine free employee choice. Arguments that card-check and remedial certification permit unionization to be “thrust” upon unsuspecting employees don’t hold weight in Canada, because labor legislation requires that collective agreements be “ratified” by majority employee vote. Strikes too must be supported by majority employee vote. Democracy is built into the Canadian model.

Of course, it remains to be seen whether Amazon and UBER will behave responsibly in the collective bargaining that is now set to begin. So far, UBER has said it intends to bargain in good faith, and let’s hope that is true. Time will tell. However, earlier this year Amazon closed its facilities in Quebec and despicably fired thousands of employees rather than allow them to benefit from collective bargaining. How Canadian labor law deals with such rogue employers prepared to take such drastic steps is a subject for another day. However, we are obviously still in the early chapters of the story of these organizing successes in British Columbia.

Daily News & Commentary

Start your day with our roundup of the latest labor developments. See all

February 8

The Second Circuit rejects a constitutional challenge to the NLRB, pharmacy and lab technicians join a California healthcare strike, and the EEOC defends a single better-paid worker standard in Equal Pay Act suits.

February 6

The California Supreme Court rules on an arbitration agreement, Trump administration announces new rule on civil service protections, and states modify affirmative action requirements

February 5

Minnesota schools and teachers sue to limit ICE presence near schools; labor leaders call on Newsom to protect workers from AI; UAW and Volkswagen reach a tentative agreement.

February 4

Lawsuit challenges Trump Gold Card; insurance coverage of fertility services; moratorium on layoffs for federal workers extended

February 3

In today’s news and commentary, Bloomberg reports on a drop in unionization, Starbucks challenges an NLRB ruling, and a federal judge blocks DHS termination of protections for Haitian migrants. Volatile economic conditions and a shifting political climate drove new union membership sharply lower in 2025, according to a Bloomberg Law report analyzing trends in labor […]

February 2

Amazon announces layoffs; Trump picks BLS commissioner; DOL authorizes supplemental H-2B visas.